St. Petersburg boasts three Imperial palaces that bear the name Mikhailovsky. There is the original Mikhailovsky Palace, built by Carlo Rossi for Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich, youngest son of Emperor Paul, which today houses the Russian Museum. Then there is the Maly-Mikhailovsky Palace on the Admiralty Embankment, built by Maximilian Messmacher for Grand Duke Michael Mikhailovich. And, finally, there is the Novo-Mikhailovsky Palace at No. 18 Palace Embankment.

Other palaces are larger than the Novo-Mikhailovsky Palace, and its near-neighbors, the Vladimir and Marble Palaces, are better known. But the building at No. 18 Palace Embankment is in many ways just as elaborate as any other Grand Ducal residence in the former Imperial capital, although it is probably the least known of St. Petersburg’s major palaces. One witty writer described it as “a prime candidate for the description Eclectic: neo-renaissance with neo-Classical porticoes, neo-Baroque caryatids and barely an inch of façade without a frieze, a panel, a bas relief…no wonder they had to invent Style Moderne.”1

Peter the Great originally granted the site along the Neva Embankment to Major Vasili Korchmin of the Preobrazhensky Life Guards Regiment. In 1719, he hired architect Domenico Tressini to create a mansion here. After Korchmin’s death in 1731, the large plot was divided into four sites and sold. One was purchased by the Dutch Ambassador to the Imperial Court, another by Lieutenant-General Michael Volkov, and a third by General A. I. Ushakov. The fourth, containing Korchmin’s original house, was purchased by Imperial Chancellor Prince Alexei Cherkassky. After Cherkassky’s death in 1742, his daughter Vavara inherited the mansion. She had the original house pulled down and commissioned architect Peter Eropkin to replace it with a large, three-story stone mansion containing more than eighty rooms and modeled on Italian Renaissance and Baroque motifs.2

Vavara Cherkasska married Count Peter Sheremetiev and the house passed into the hands of the famous aristocratic family. In 1807, the Imperial Department of Appanages purchased the former Cherkassky Mansion, as well as adjoining houses belonging to the Golitsyn and Zubov families. Architect Andrei Voronikhin was commissioned to redesign the interior to accommodate the new offices, although he left the existing façade intact.3 An astonishing 114,000 rubles were spent redecorating the palace in a suitably grand style. It was here, for a year, that a young Nicholas Gogol worked as a clerk.4

In 1857 Grand Duke Michael Nikolaievich, the fourth son of Emperor Nicholas I, turned twenty-five. He was a tall, imposing man, with blue eyes and a face cloaked in a long beard and bushy sideburns. Michael Nikolaievich was a military man through and through, as his son Alexander Mikhailovich recalled: “Following in the steps of his uncompromising father Nicholas I, my father thought it only natural that his sons should be reared in an atmosphere of militarism, strict discipline, and exacting duties. Inspector-general of the Russian artillery and viceroy of an enormously rich, half-Asiatic province incorporating some twenty-odd nationalities and fighting tribes, he had but small regard for the niceties of modern education.”5

On August 18, 1857, Grand Duke Michael Nikolaievich married Princess Cecilia of Baden. A few months earlier, anticipating the upcoming union, Nicholas I decided that the prestigious location of the Cherkassy Mansion on Palace Embankment facing the Neva would be perfect for Michael Nikolaievich’s new residence as a married man. The Imperial Department of Appanages was moved to a different location in St. Petersburg. But, although the plot on which the mansion stood was of considerable size, it was not large enough for the extravagantly vast palace envisioned for the Grand Duke. And so, the Crown turned its attention to the plots adjoining the Cherkassy Mansion to the south, purchasing existing houses belonging to the Golitsyn and Zubov families to create a sizable building site that stretched from the Neva Embankment to the Millionnaya.6

Architect Andrei Stackenschneider was given the commission for the new palace. By this time, the fifty-five-old Stackenschneider was firmly entrenched as an Imperial favorite. His first major project for the Romanovs was the Mariinsky Palace, built for Emperor Nicholas I’s daughter Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaievna on St. Isaac’s Square in a kind of modified Empire style that also incorporated the Baroque elements which would become Stackenschneider’s hallmark. Over the next two decades, the architect designed the Nicholas and Beloselsky-Belozersky Palaces in St. Petersburg as well as the Pavilion Hall in the Small Hermitage; the Leuchtenberg villa Sergievka on the Gulf of Finland; Oreanda in the Crimea; and the Farmhouse Palace as well as the Tsaritsyn, Olga, and Belvedere Pavilions at Peterhof.7

Construction of what became the Novo-Mikhailovsky Palace, to differentiate it from the late Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich’s immense residence, began in 1857 and lasted until 1861. To save money, Stackenschneider incorporated the former Cherkassy Mansion into the new building, although the finished building ended up costing the Imperial Treasury just under 1 million rubles.8 The Palace utilized the latest construction techniques. Steel beams supported floors and walls and held up the roof; the structure was equipped with gas and featured the newest plumbing and sewage systems, as well as forced air heating to ward off the chilly St. Petersburg winters.9

The finished palace was a massive building of three stories atop a raised, rusticated ground floor. It completely dwarfs the Florentine-style Vladmir Palace to the west. The Novo-Mikhailovsky Palace façade facing the Neva is a veritable riot of decoration, a confusing mélange of Baroque, Rococo, and Italianate elements discordantly thrown together as if Stackenschneider grabbed a handful of architectural details, tossed them at the building, and was content to use whatever stuck.10 Rows of pilasters march along the first floor, framing rectangular windows topped with carved bas-reliefs and supporting the entablature above. The decoration along the second floor is more elaborate, with Corinthian columns and pilasters flanking rounded windows topped with arched hoods. A stringcourse delineates the third story, with smaller, almost square windows placed between pilasters. A neoclassical balustrade topped with urns runs along the top cornice, shielding the hipped roof of green metal sheeting.11

Even more elaborate decoration marked the two slight end projections as well as the one at the building’s center. Along the second floor of these wings, Stackenschneider deployed Corinthian columns of Carrara marble to flank arched windows topped with triangular hoods: each of the central windows in these projections is crowned by carved scrolls and bas-reliefs and topped by rounded pediments which rise into the third story. Along the third floor these pediments, as well as the marble columns, are adorned with carved caryatids and set with terracotta sculptures by David Jensen, reaching to wide triangular pediments along the cornice of the roof, their gable ends marked with additional statuary. The central projection contains the main entrance, shielded by a canopy of triple arches rests atop twisted cast-iron columns and is flanked by immense wrought iron lamps. Here, the second-floor columns support a curved pediment, which in turn is topped with more statuary before rising to a triangular pediment rising above the surrounding balustrade and containing Grand Duke Michael Nikolaievich’s Coat-of-Arms carved in marble.12 Though undoubtedly grand, the Novo-Mikhailovsky Palace is overwhelming, confusing in its decoration, and pompous in manner.

After the riotously overwrought façade, the eclectic interiors almost come as a relief. Although they, too, swing wildly from style to style, at least the differences are contained in their own hermetic spaces. The interior décor was carried out in Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, Louis XVI, and Gothic designs. Many of the walls and ceilings featured sculptured reliefs, paintings and decorative details by Jensen, Michael Zichy, and Nicholas Tikhobtazev; other rooms were hung in colored silks or adorned with stamped and gilded leather. Intricately carved wooden wainscot, doors, and ceilings in the private apartments contrasted with neoclassical pilasters, stucco details, and abundant marble in the ceremonial halls, which also contained floors inlaid with rare woods in geometric designs.

From the Palace Embankment, guests entered a marble vestibule lined with eight columns and eighteen pilasters of gray granite topped by white Corinthian capitals. An archway opened directly to an Imperial staircase of marble fringed with an intricate wrought-iron balustrade detailed in bronze and ormolu. The walls of the staircase were detailed with stucco reliefs, decorative panels and flanking pilasters rising to a deep cornice and plafond circling a compartmented ceiling with arabesques and foliage designs.13

At the landing a large, mirrored door opened directly into the Winter Garden, built in a curious U-shape to surround the projection containing the staircase. This rose two stories, and was filled with palms, boxed orange trees, and a variety of exotic plants and flowers. Nine tall windows, overlooking the inner courtyard, flooded the space with light.

The ceremonial halls occupied the second floor overlooking the Neva. These were arranged en enfilade, their doorways aligned to provide a vista from one end of the palace to the other. Three of these took their names from their decorative scheme: the Crimson, White, and Yellow Drawing Rooms, all hung in silk panels in carved and gilded moldings which matched the cornices and ceiling details; inlaid floors; and marble fireplaces topped with large mirrors. Pilasters topped with gilded Corinthian capitals ringed the State Reception Room, framing alternating panels hung with silk and lavish arabesque designs in gold. An intricately decorated frieze circled the room beneath a plafond bisected by carved cartouches and foliate designs.14

The three largest rooms rose into the third floor, with double rows of windows. The Green Hall was a frothy space of elaborate stucco reliefs of laurel wreaths, swags, foliage, and cherubs picked out in white and gold against mint-colored walls. A frieze was set with relief panels of white figures against a cream ground separated by volutes; the deep plafond alternated painted rondels with bas-relief panels, rising to a ceiling heavily adorned with gilded stucco ornaments including acanthus leaves and rosettes.

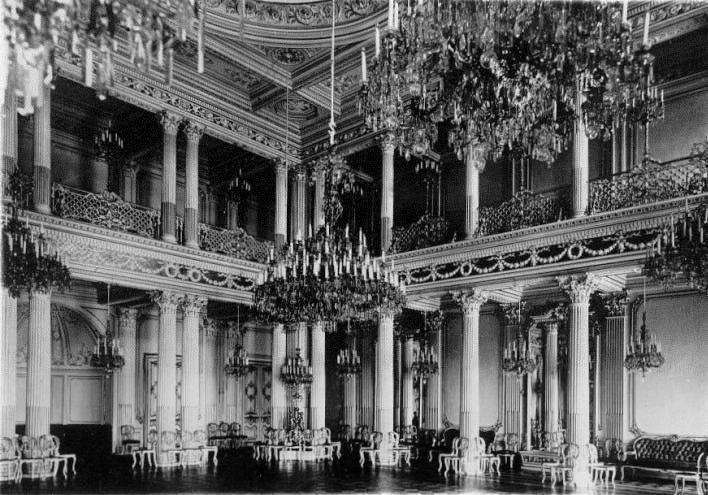

The Banquet Hall looked out onto the inner courtyard. The northern and southern ends were delineated by two-tiered colonnades, their detailing picked out in gilt. Elaborate stucco reliefs were used on the wall panels and on the segmented ceiling, hung with a massive crystal and ormolu chandelier. The Dancing Hall overlooked the Neva. The room, too, was distinguished by a two-tiered colonnade of white Corinthian columns that ringed three sides.15

The space in the middle of the third floor was given over to the Church of the Archangel Michael, marked on the exterior by a small cupola and golden dome. A. E. Beideman painted the walls and vaults of the ceiling using medieval Muscovite motifs in gold and crimson against a blue background.16

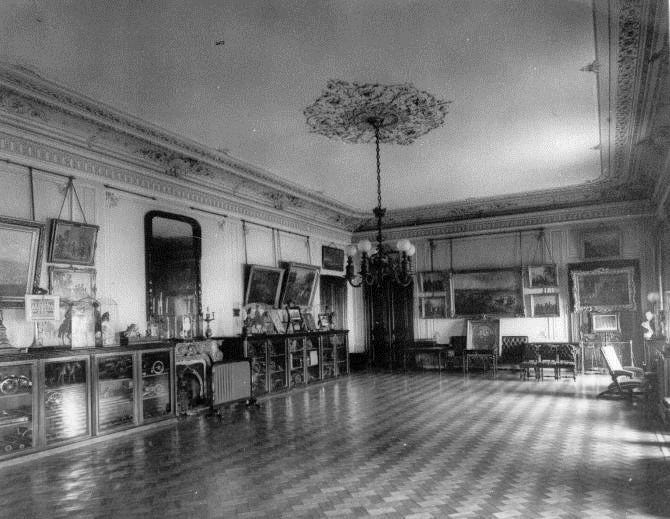

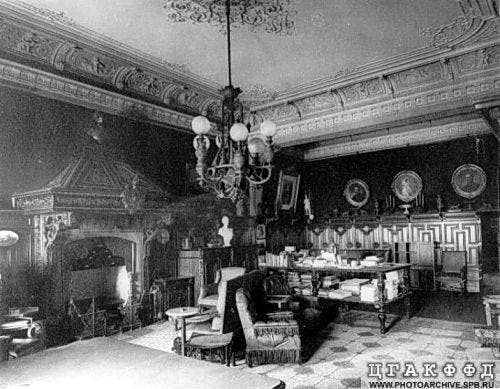

The principal private apartments of the Grand Duke and his family were situated on the ground floor. The Grand Duke’s Reception Room was a relatively restrained apartment, with the decoration restricted to an ornamental cornice and a ceiling fringed with delicate paintings surrounding a central stucco relief from which hung a brass chandelier whose frosted globes were illuminated by gas. Low cabinets ringed the walls, displaying various pieces from Michael Nikolaievich’s collection, while numerous paintings cloaked the space between cabinets and cornice. An elaborately carved walnut wainscot circled the lower walls of the Grand Duke’s Study; above this hung a crimson patterned silk. A massive fireplace, with a splayed and carved walnut hood, dominated one wall; this bit of eclectic fantasy stood in contrast to the rather neoclassical frieze and cornice surrounding a white ceiling set with stucco reliefs, but it was not the only incongruous touch. Heavy, overstuffed chairs dripping with fringe stood beneath a bronze gasolier while porcelains fought with potted palms for primacy.17

The Oak Dining Room served the family for private meals. Taking its name from the carved wainscot which ran around the lower half of the walls, this was executed in a vaguely baronial style, with Gothic elements tossed in to decorate the coffered wooden ceiling supported by elaborate brackets decorated with antlers. The upper walls were covered in leather embossed in gold, and the ceiling was hung with a large, multi-branched chandelier adorned with copper leaves and bunches of grapes.18

Grand Duchess Olga Feodorovna’s rooms were executed in a number of similarly vague though luxurious styles, with brocaded silks on the walls and neo-Rococo overstuffed furnishings. The one real surprise was a large indoor pool. Other Grand Ducal residences would feature deep plunges in their private apartments, but the Novo-Mikhailovsky Palace was unique in having the only shared bathing pool. The walls were lined with pink scagliola framed with green marble, while pilasters of the same green marble were topped with Doric capitals. The nautical theme was carried out in a frieze decorated with bas-reliefs ships and even the doors sported figures of gilded dolphins.

On the southern side of the site, facing the Millionnaya, a second building was erected and linked to the main structure by curved wings which enclosed an internal courtyard. As this was principally intended to house Grand Duke Michael Nikolaievich’s sons as well as courtiers and servants, Stackenschneider’s muted Italianate façade was less exuberant than the one along Palace Embankment, decorated with pilasters, floral reliefs, and Rococo swags. A central arched opening, set with an elaborate wrought iron gate, gave access from the Millionnaya to the courtyard. Altogether the wing contained seventy-seven separate apartments, ranging from one room (for servants) to a dozen for the Grand Ducal sons. The accommodations were less than idea: not only did many of the rooms overlook the inner stables but only sixteen of these apartments had their own bathrooms attached.19

Work on the Novo-Mikhailovsky Palace was finished in the autumn of 1862, but ironically the family would not take up permanent residence for nearly another two decades. In December 1862, Alexander II appointed his brother Grand Duke Michael Nikolaievich as Viceroy of the Caucasus, the entire family moved to Tiflis. They returned only rarely to St. Petersburg, staying at their immense palace for a week or two or at their country estate on the Gulf of Finland.

The assassination of Alexander II in 1881 finally brought the family back to St. Petersburg. Alexander III appointed his uncle to the post of Chairman of the State Council, which meant relinquishing his position in the Caucasus. Only now did the palace overlooking the Neva become a full-time residence. By this time, though, the family was largely scattered. Only daughter Anastasia had been married off to the Hereditary Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and the eldest sons were serving in the military.

In 1891, after several years of high drama surrounding the couple’s second son Michael’s efforts to marry Countess Katya Ignatieva, he entered a morganatic union with Pushkin’s granddaughter and was exiled from Russia. Just a few days after learning of this marriage, Grand Duchess Olga Feodorovna suffered a fatal heart attack while traveling to the Crimea. Grand Duke Michael Nikolaievich had genuinely loved his wife and was devastated by the loss.

A pall descended over the Novo-Mikhailovsky Palace. “My father,” recalled Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich, “walked aimlessly from room to room. He remained silent for hours, smoking thick black cigars, one after another, and staring through the long half-lighted corridors, as though hoping that a familiar voice would sound reminding him that he was not supposed to do his puffing in the drawing room. He blamed Michael's marriage for aggravating mother's illness, and he could not forgive himself for letting her go alone to the Crimea. He was fifty-nine…. His Caucasus and his wife, nothing else ever mattered for him. Nothing at all was left for him to live for now.”20

In 1894 Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich wed Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna, eldest daughter of Emperor Alexander III, and a year later the youngest Mikhailovichi son, Grand Duke Alexei, died of tuberculosis at the age of twenty. The other sons, though – Nicholas, George, and Sergei – all kept apartments in their father’s palace. In 1900 George, who like all Romanov males served in the military but was only interested in his valuable coin collection, married Princess Marie, daughter of King George I of the Hellenes, and the couple moved into a large apartment in the palace.

The new Grand Duchess Marie Georgievna was discouraged after inspecting the suite. “I had to work hard for quite a long time to make the rooms really livable,” she later wrote, “and it was lucky that this was so: if I had not been so busy I should have suffered even more than did I from homesickness. Our palace…was a colossal building. In fact, my husband’s youngest brother Sergei who lived quite at the other end of the house always bicycled from his rooms to ours…. The furniture was rather Victorian looking and stiff. The apartment had been furnished in 1857 for my father-in-law’s marriage. All the state rooms had the most beautiful parquet floors, like those of the other palaces of Petersburg, inlaid with rarest woods of different colors in lovely designs. Two of my husband’s unmarried brothers, as well as my father-in-law, lived in the palace; they were the Grand Dukes Nicholas and Sergei Mikhailovich. We always had meals with my father-in-law. Luncheon was a state meal with all the court in attendance in a huge dining room, the walls of which were covered with beautiful Cordova leather. From this room one had a superb view of the Neva with the fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul on the opposite side. I did not much enjoy those luncheons because I always had to sit opposite my father-in-law and had various old generals as neighbors – which was not very amusing.”21

Marie confessed that she “hated” the reception rooms “because they were so old fashioned and stiff. My father-in-law had told me to rearrange them in my own way but when he saw the changes I made he was very much upset, and everything had to be put back again as before. I only insisted upon having the part where I had to sit with the ladies arranged as I pleased.” At least she was allowed to decorate her sitting room according to her own tastes, with overstuffed, chintz-covered sofas and various souvenirs of her former life in Greece. On the floor she placed a large Wolf-skin rug, given to her by Princess Zinaida Yusupov. This once caused an accident, as she tripped over it and ended up having to use crutches for several days.22

The Grand Duchess, the only lady in the household, found herself serving not only as her husband’s partner but also as her father-in-law’s official hostess. In January 1903 Crown Prince Wilhelm of Germany arrived in St. Petersburg, and Grand Duke Michael Nikolaievich decided to give a ball in his honor. “This,” Marie recalled, “was my first experience of playing hostess on such an important occasion, and I felt rather alarmed. I am glad to say that it all went off without a hitch and the whole world of St. Petersburg appeared to enjoy it enormously. The Prince was charming and had great success among the ladies.”23

Each winter, Grand Duke Sergei Mikhailovich organized musical evenings in the palace, with an orchestra and a choir in which he himself sang, as Marie remembered, “with his fine bass voice. Concerts took place twice a week in the great banqueting hall of our palace. I used to sit next door and listen. One evening Sergei told me to arrange a private dinner for the Emperor and Empress in our apartments as he was going to ask the famous Basso Chaliapin to sing for us. Chaliapin’s voice was then at the acme of its glory, and he was one of the idols of the music-loving Russia. Their Majesties accepted our invitation with joy, and after dinner we all proceeded to the hall to hear the men’s choir. During an interlude Chaliapin appeared, smiling and debonair as usual, announcing in his great deep voice, ‘Here I am.’ When he recognized the Tsar, about whose presence he had not been informed, he nearly ran away. Sergei caught him just in time. He sang divinely that evening. After the great basso had finished singing, we took tea in the next room and the Emperor wished Chaliapin to be presented to him. They had a friendly talk and afterwards the Emperor handed him a glass of champagne and drank to his health. Chaliapin drained the glass and put it into his pocket, asserting in a loud voice that he intended keeping the goblet as a souvenir. It was one of my best Bohemian glasses, and I never saw it again.”24

In 1903 Grand Duke Michael Nikolaievich suffered a stroke which left him partially paralyzed and confined to a wheelchair. He began spending long periods of time in the South of France, where he was reunited and reconciled with his exiled son Michael and his new family. It was at Cannes that, on December 5/18, 1909, Grand Duke Michael Nikolaievich died, the last of Nicholas I’s children.

The Novo-Mikhailovsky Palace passed to Michael’s eldest son, Grand Duke Nicholas Mikhailovich. Although he served in the military, the Grand Duke was a man of two passions: butterflies and history. He published a ten-volume study of butterflies; a history of Russo-French diplomatic relations; and a number of historical biographies of his Romanov ancestors. He became Chairman of the Russian Historical Society in 1909 and held the post until the Revolution. By inclination he was a liberal, although he fully embraced all the privileges of being a Russian Grand Duke.

With an eye to history, Nicholas Mikhailovich created a museum dedicated to his father in four of the palace’s rooms. This showcased Michael Nikolaievich’s tenure as Viceroy in the Caucasus; his role in the Russo-Turkish War; and his time as Chairman of the State Council. Select visitors could examine Michael Nikolaievich’s documents and letters; portraits and photographs; and weapons and works of art from his collections.25

Nicholas Mikhailovich seems to have left most of the palace rooms as they had been during his father’s life. He spent most of his time in the large, two-story library, studying his collection of books. The Grand Duke’s study was a more personal space. Divided by a triple open archway inset with carved walnut coffers to match the wainscot, it showcased a profusion of paintings and souvenirs crowded onto every available inch of space. A massive desk of indeterminate period stood near one of the windows, contrasting with a distinctly Empire-style armchair inlaid with ormolu reliefs. The rest of the furnishings were typical of the Victorian era: overstuffed, fringed sofas and chairs scattered atop Oriental carpets dotted with potted palms.

After the Revolutions of 1917, the Novo-Mikhailovsky Palace was nationalized. Grand Duke Nicholas Mikhailovich was arrested and, together with his brother George and Grand Duke’s Paul Alexandrovich and Dmitri Konstantinovich, imprisoned in the Fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul. In January 1919, all four Grand Dukes were shot, and their bodies dumped into a common grave in the fortress yard.

The Palace became the headquarters of the Communist Academy and the Leningrad Military District. The Church of the Archangel Michael was dismantled, as was the swimming bath. Although the ceremonial halls were left intact, the private apartments became offices and classrooms, divided by partitions nailed directly into the elaborately decorated walls. The wing overlooking the Millionnaya housed the Bukharan Embassy. Later, it was divided into communal apartments. And in 1950 the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Academy of Science took over the palace. It remains housed in its rooms today.26

During the Soviet and post-Soviet period, the palace disintegrated. The barest of routine maintenance was done, but the elaborate exterior overlooking the Neva had suffered from years of neglect. The bas-reliefs and terracotta sculptures had cracked in the harsh St. Petersburg winters, and bits of masonry crumbled and fell to the street. In 2005, work finally began to preserve and restore the façade. This endeavor was largely funded by the Sultan of Oman, who valued the Institute’s rare collection of Eastern and Oriental manuscripts. This work was finished in 2010, ensuring that the Novo-Mikhailovsky Palace will be preserved for future generations.27

Source Notes

1. Zinovieff and Hughes, 302.

2. Citywalls.ru; Malinovskiy, 318; Frolov, 44; Pazin, 54.

3. https://www.citywalls.ru/house1913.html.

4. Pazin, 56; Frolov, 47.

5. Alexander Mikhailovich, 19.

6. Petrov, 316; Frolov, 49; Pazin, 58-59.

7. Petrova, 211; Frolov, 51.

8. Citywalls.ru.

9. Citywalls.ru; Punin, 96-100; Petrov, 316; Frolov, 52; Pazin, 60.

10. Citywalls.ru.

11. Petrov, 316; Frolov, 52; Pazin, 61-62.

12. Vasilievskaya and Vasilievskaya, 103; Citywalls.ru; Punin, 207; Burdyalo, 146-150; Petrov, 316; Frolov, 55; Pazin, 62.

13. Frolov, 57.

14. Frolov, 57; Pazin, 64.

15. Citywalls.ru; Petrov, 316; Frolov, 58; Pazin, 65.

16. Citywalls.ru.

17. Ibid.

18. Citywalls.ru; Pazin, 66.

19. Citywalls.ru; Punin, 207; Petrov, 316; Frolov, 60; Pazin, 67-68.

20. Alexander Mikhailovich, 136.

21. Marie Georgievna, 80-81.

22. Ibid., 96.

23. Ibid., 101.

24. Ibid.

25. Pazin, 69-70.

26. Citywalls.ru; Petrov, 316; Frolov, 60; Pazin, 69.

27. Frolov, 62-63; Pazin, 71.

Bibliography

Alexander Mikhailovich, Grand Duke of Russia. Once a Grand Duke. New York: Farrar & Rinehart, 1932.

Citywalls.ru

Frolov, A. Velikogertsogskiye dvortsy. St. Petersburg: Glagol, 2008.

Malinovskiy, K. V. Peterburg XVIII veka. St. Petersburg: Kriga, 2008.

Marie Georievna, Grand Duchess George. A Romanov Diary. New York: Atlantic International, 1988.

Pazin, Mikhail. Zapretnyye strasti velikikh knyazey. St. Petersburg: Piter, 2009.

Petrov, V. Pamyatniki arkitektura Leningrada. Leningrad: Stroyizdat, 1976.

Petrova, T. A. Andrey Stackenschneider. Leningrad: Lenizdat, 1978.

Punin, A. L. Arkhitektura Peterburga serediny XIX veka. Leningrad: Lenizdat, 1990.

Vasilevskaya, N., and Ye. Vasilievskaya. St. Petersburg: A Guide to the Architecture. St. Petersburg: Bibliopolis, 1994.

Zinovieff, Kyril, and Jenny Hughes. The Companion Guide to St. Petersburg. London: Companion Guides, 2003.