The Last Imperial Palace: The St. Petersburg Residence of Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich, Jr.

by Greg King

It stands along the Neva River in St. Petersburg, a small, neoclassical building with a rounded corner topped by a small dome. There is nothing about it that suggests it was once an Imperial residence: indeed, it looks absurdly small. Yet No. 2 Petrovskaya Street, poised along the north side of the Neva River and looking south to Palace Quay, was indeed home to a Romanov, being the last palace built by a member of the Dynasty in the Imperial capital.

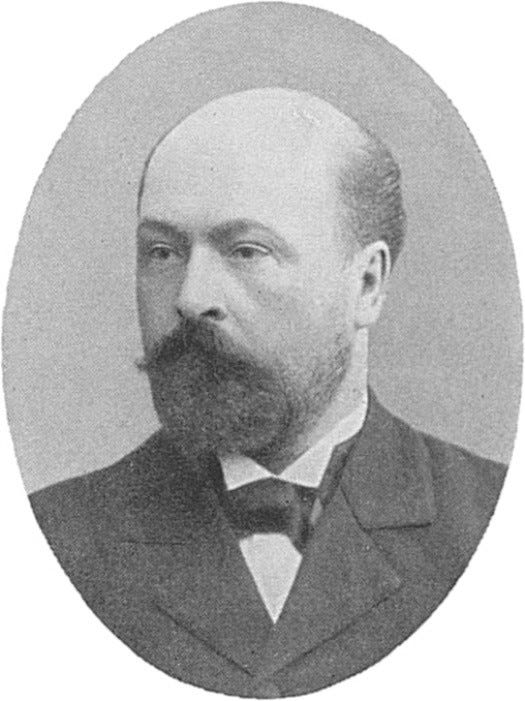

The Palace is bold, severe, and solid, in fitting with the character of the man for whom it was built. Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich Jr., born in 1856 to Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich and his wife Grand Duchess Alexandra Petrovna, was a soldier by vocation and character. Having graduated from the Nikolaev Engineering School and the Academy of the General Staff, he had risen through the military ranks, becoming Inspector-General of the Cavalry; Commander of the Guards; Commander of the St. Petersburg Military District; and Chairman of the Defense Council. Stern, intimidating, and blunt, he was feared more than respected, even within the Imperial Family.

It was odd that such a pivotal figure in the Romanov Dynasty did not have his own palace in the Imperial capital until midway through Nicholas II’s reign. The Grand Duke, though, cared little about such matters, and usually stayed at either his suburban palace of Znemenka on the Gulf of Finland or at the apartment he shared with his brother Grand Duke Peter Nikolaevich and his family. But in 1907 the Grand Duke married Anastasia, daughter of Nicholas I of Montenegro and recently divorced from her first husband the Duke of Leuchtenberg. It was this marriage that finally convinced the Grand Duke to build his own residence in the Imperial capital.

Nearly all grand ducal residences in St. Petersburg were situated in the main part of the city, south of the Neva; for his own palace, Nicholas Nikolaevich selected a site along the Neva’s northern Petrovskaya Embankment, near the new Trinity Bridge and a granite landing flanked by stone figures depicting lions. The plot of land had come to Nicholas Nikolaevich and his brother Peter Nikolaevich in 1893, when they settled their late father’s estate. At some point, Peter sold his interest in these two sites to his brother. On the first site, located at No. 3, the Grand Duke built a six-story apartment block, which was completed in 1909. The second plot, at No. 2, was to be the site of the Grand Duke’s new palace.1

The Grand Duke commissioned architect Alexander Sergeievich Khrenov to build both the apartment block and his new palace. Born in 1860, Khrenov had graduated from the Imperial Academy of Arts in 1884 and in 1888 he became the chief architect assigned to preservation of St. Isaac’s Cathedral. Most of his work in the Imperial capital consisted of residential apartments. In 1903 he had built a mansion for M. F. Tetzner, wife of a wealthy merchant, at No. 5 Tverskaya which today houses the consulate of the Czech Republic. The Grand Duke’s palace was his only other private residential commission.2

Work on the new palace began in 1910 and took three years. The finished building was a square structure of three-stories, its exterior executed in pale white limestone. Neoclassical in style, it was restrained in its details. A stringcourse separated the ground floor from the two main floors. While the ground floor was severe to the point of austerity, the upper stories carried the building’s decorative details. The façades facing the Neva and Trinity Square were adorned with central, triangular pediments, each supported by four Corinthian pilasters. The southeastern corner was curved, centered on a half-rotunda topped by a pediment carved with the Grand Duke’s coat-of-arms and crowned by a low bronze dome. Elaborate wrought iron gates opened to the side courtyard. Here, the façade was quite different, executed in a sort of vaguely Art Nouveau style, with plain pilasters flanking the main entrance.3

The palace interiors were executed in a variety of materials, including red and gray Finnish granite and marble, with ormolu and Karelian birch used for decorative details. A monumental staircase, its railing insets of sculpted steel and bronze, ascended to the main floor beneath a leaded glass dome. There were few ceremonial rooms: a drawing room fringed by a stucco cornice; a dining room lighted by semicircular windows; a library ornamented in carved oak; and a delicate, almost Rocoo-style reception room overlooking the Neva. The Grand Ducal apartments filled most of the third floor and were furnished with Art Nouveau-style pieces ordered from the firm of Roman Meltzer.4

The Palace was completed in 1913. But the Grand Duke was not to live within its walls for more than a year. In 1914, on the outbreak of World War I, Nicholas II named the Grand Duke Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Armed Forces, and Nicholas Nikolaevich took up residence at General Headquarters, located in the town of Baranovichi, living in his train. Anastasia, busy with war relief work and organizing hospital trains, continued to live in the palace during her infrequent stays in the Imperial capital.

In the late summer of 1915, Nicholas II decided to assume Supreme Command; Nicholas Nikolaevich was named Governor-General of the Caucasus and Commander of the Caucasian Front and, with Anastasia, moved to Tiflis. They never returned to live in their palace, instead taking up residence after the Revolution at Anastasia’s Crimean estate of Tchair before finally moving to Dulber, the Crimean palace owned by the Grand Duke’s brother Peter Nikolaevich. In April 1919 they, along with Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna and other members of the Romanov Dynasty who had sought refuge on the peninsula, were evacuated by British warships. The Grand Duke and his wife spent the rest of their lives in exile in France.

The Palace of Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich Jr. was one of the first Romanov residences to be taken over for state use, housing the Investigative and Legal Commission of the Central Executive Committee following the October Revolution. Suspected counterrevolutionaries were brought before tribunals here before being either released or sent to the Cheka. In 1918 the building was given to the State Institute for the Study of the Brain, which occupied the premises until 1954, when it was supplanted by the Institute of Semiconductors and then the Institute of Lake Studies. In 1985, the building became Leningrad’s Wedding Palace No. 3; to accommodate the thousands of brides and grooms who passed through its rooms, the main entrance was moved from the courtyard to the Neva Embankment. But most of the interior was preserved intact, and so the building remained much as it was in 1913. In 2000, it was transferred to the Federal Government and now serves as the offices and residence of the Northwestern Federal District’s Representative of the Russian President.5

Source Notes

1. Citywalls.ru; http://sergekot.com/dvorets-nikolaya-nikolaevicha-mladshego/; https://dzen.ru/a/Z0r9Cok53jcigsXS; https://spbinteres.ru/dvorec-nikolaya-nikolaevicha-mladshego.html; Vasilevskaya and Vasilevskaya, 306; Frolov, 289; Kirikov, 273.

2. Kirikov, 273; Vasilevskaya and Vasilevskaya, 307; Frolov, 373.

3. https://stavnistavim.ru/raznoe/dvorec-velikogo-knyazya-nikolaya-nikolaevicha-mladshego-dvorec-nikolaya-nikolaevicha-mladshego-v-sankt-peterburge-dvorec-velikogo-knyazya-nikolaya-nikolaevicha-mladshego.html; Citywalls.ru; http://sergekot.com/dvorets-nikolaya-nikolaevicha-mladshego/; https://spbinteres.ru/dvorec-nikolaya-nikolaevicha-mladshego.html; https://dvorspb.ru/sights/architecture/palaces/nikolay-nikolaevich-palace/; Vasilevskaya and Vasilevskaya, 306.

4. Citywalls.ru; http://sergekot.com/dvorets-nikolaya-nikolaevicha-mladshego/; https://dzen.ru/a/Z0r9Cok53jcigsXS; https://spbinteres.ru/dvorec-nikolaya-nikolaevicha-mladshego.html; https://stavnistavim.ru/raznoe/dvorec-velikogo-knyazya-nikolaya-nikolaevicha-mladshego-dvorec-nikolaya-nikolaevicha-mladshego-v-sankt-peterburge-dvorec-velikogo-knyazya-nikolaya-nikolaevicha-mladshego.html; Frolov, 292; Kirikov, 274.

5. https://dvorspb.ru/sights/architecture/palaces/nikolay-nikolaevich-palace/; https://spbinteres.ru/dvorec-nikolaya-nikolaevicha-mladshego.html; https://dzen.ru/a/Z0r9Cok53jcigsXS; Citywalls.ru; http://sergekot.com/dvorets-nikolaya-nikolaevicha-mladshego/; https://stavnistavim.ru/raznoe/dvorec-velikogo-knyazya-nikolaya-nikolaevicha-mladshego-dvorec-nikolaya-nikolaevicha-mladshego-v-sankt-peterburge-dvorec-velikogo-knyazya-nikolaya-nikolaevicha-mladshego.html; Vasilevskaya and Vasilevskaya, 307; Frolov, 293.

Bibliography

Frolov, A. Velikogertsogskiye dvortsy. St. Petersburg: Glagol, 2008.

Kirikov, B. M. Arkhitektura Peterburga kontsa XIX-nachala XX veka: eklektika, modern, neoklassitsizm. St. Petersburg: Kolo, 2006.

Vasilevskaya, Nina, and Yelena Vasilevskaya. Saint Petersburg: A Guide to the Architecture. St. Petersburg: Bibliopolis, 1994.

Internet Resources

Citywalls.ru

http://sergekot.com/dvorets-nikolaya-nikolaevicha-mladshego/

https://dzen.ru/a/Z0r9Cok53jcigsXS

https://spbinteres.ru/dvorec-nikolaya-nikolaevicha-mladshego.html

https://dvorspb.ru/sights/architecture/palaces/nikolay-nikolaevich-palace/