On October 17/30, 1905, in his study in the Lower Palace at Alexandria, Peterhof, Nicholas II signed the manifesto establishing the State Duma as Russia’s first elected parliamentary body. He did so reluctantly, and under immense pressure. The country was in crisis, and concessions were inevitable. For more than a year the Emperor had toyed with various proposals to create a Duma as a way to appease the growing unrest, though all were to be merely consultative in nature. In 1904 he had discussed granting an elected body which could offer advice on proposals before the State Council, though all decisions would be made solely by the Emperor. In January 1905, he announced that a commission would examine the question of a representative body; to its members he made clear that any recommendations should avoid “constitutional and parliamentary forms that are alien to us,” in other words, a body that infringed on his prerogatives. He echoed these sentiments in a manifesto issued on February 18. An elected body would have the right to evaluate and discuss proposed legislation, but Nicholas would preserve the autocracy.

By October 1905, though, the war with Japan had ended disastrously, and strikes had paralyzed the country. Under the influence of an insistent Sergei Witte and Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaievich, as well as other voices advising Nicholas to make a dramatic step, the Emperor duly agreed to grant not only a parliament but also basic civil rights. With the sweep of a pen, Nicholas II had ended autocratic rule in Russia. He knew it, though he was reluctant to admit it. Instead, he clung to a belief that he had granted these concessions freely, as a gift to the Russian people made by his autocratic will. Although he promised that his decision was “irrevocable,” Nicholas would make serious attempts over the next decade to go back on his word and reduce the Duma to a purely consultative body, or to eliminate it altogether.

Elections for the new Duma took place even as the Emperor met with advisors to discuss the necessary revisions to the Fundamental Laws of the Russian Empire. Battles immediately ensued when Nicholas insisted that the line “To the Russian Emperor belongs the supreme autocratic and unlimited power” be left as it was. Seasoned bureaucrats pointed out that the word “unlimited” no longer applied, as Nicholas had agreed to share legislative power with the Duma. “I have not ceased thinking about this problem since the project for a review of the Fundamental Laws came before my eyes for the first time,” he told the council charged with revising the laws. He explained that he was “tormented” by the question of “whether I have the right before my ancestors to change the boundaries of the power I received from them.” Although insisting that “if I were convinced that Russia wanted me to renounce my autocratic rights, I would do this gladly,” he declared that he was not “convinced of the necessity” to do so. After several days of arguments, Nicholas reluctantly agreed that the word “unlimited” should be deleted from the new laws.1

The revised Fundamental Laws were published on April 23, 1906. The new Duma was set to convene in just four days. Before this happened, though, Nicholas replaced Sergei Witte with Ivan Goremykin as the new Chairman of the Council of Ministers. Where Witte had been abrasive and smug, Goremykin was servile and shared Nicholas II’s ideas that the autocracy continued after October 1905. Conservative and reactionary, he could be relied on to represent the Emperor’s views in the impending and unknown legislative body, which was given use of a transformed Winter Garden in the magnificent Tauride Palace for their sittings.

For weeks the Imperial Court held intense discussions about the convocation of the Duma. The event was unprecedented in Russian history, and no one knew quite how to approach it, resulting – as historian Orlando Figes so aptly put it – in “delicate maneuvers in a beautifully camouflaged battle.”2 More conservative elements in the Imperial Suite argued that the Emperor should simply ignore the gathering. This fit in with Nicholas’s own inclinations. He seemed content to simply let the assembly meet without Imperial recognition. Perhaps, he suggested, he might invite a few of the Duma members to a later private reception at the palace, but he was reluctant to give the legislature he had been forced to create any sign of his favor. But liberal advisors warned that it was impossible for the Emperor to so publicly slight such an important body which he himself had brought into existence. If Nicholas appeared before the assembled body at the Tauride Palace and inaugurated its first session, this would be seen as a conciliatory gesture and taken as evidence that he fully embraced the Duma. Officials eventually decided to follow the model set by the Kaiser: he welcomed members of the Reichstag in the Berlin Palace and delivered a formal address from the Imperial Throne. Nicholas would therefore ask the elected representatives to the Winter Palace. They would gather in St. George’s Hall, the Imperial Throne Room, the sanctum sanctorum of the autocracy, where he would make a speech before they met in the Tauride Palace.3

This decision, perhaps inevitable, represented a missed opportunity. As historian Helene D’Encausse wrote, it was a “disastrous idea” to keep Nicholas II away from the Tauride Palace to inaugurate the new Duma.4 Had he gone to the new delegates and welcomed them to their new home, he would at least have created considerable goodwill. But the impression that it would have created among some – Imperial capitulation – was precisely the worry that led officials to abandon such talk.

As Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich recorded in his diary, it was the Empress who planned the resulting ceremony. She explained to him that she “tried to avoid imitating western models, and to remain in keeping with Russian customs.” The Grand Duke, though, was not convinced: “I very much doubt whether she is familiar with these customs, and anyway how to adapt them to a parliament?”5 Alexandra had initially wanted to create a grand spectacle, with the small Imperial yacht Alexandria carrying the entire Romanov family from Peterhof to the capital and along the Neva to the embankment of the Winter Palace. But it was April: no one could predict the weather and, in any case, more seasoned voices argued that it would be extremely uncomfortable and awkward to have both Empresses and the Grand Duchesses standing on deck for an hour wearing Russian Court dress with tiaras, jewels, and orders.6 In the end, only Nicholas II, Empress Alexandra, Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna and the most immediate members of the Imperial Family would arrive by yacht; the rest of the Grand Dukes and Grand Duchesses would simply gather in the Winter Palace as they did for any other court occasion.

Finally, April 27 arrived. Worries about the weather turned out to be empty: it was a brilliant and warm spring day in St. Petersburg, an exceptional turn for what promised to be an exceptional occasion. It was declared a public holiday: church bells rang out across the capital, and flags and bunting decorated official buildings to mark the occasion. Private citizens were also encouraged to display flags, although officials secretly worried about possible revolutionary activity.7

Potential dangers had kept Nicholas II and his family virtual prisoners at either Peterhof or Tsarskoye Selo for more than a year, as the Revolution of 1905 played itself out.8 This day would see the Emperor’s first public appearance in the capital since the Epiphany Ceremony of January 1905, when a live shell fired from the guns of the Fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul had crashed into the Palace Embankment, shattering windows and sending officials scrambling. Three days later, police had opened fire on processions of factory workers, holding aloft icons and pictures of Nicholas II, as they marched across the capital to the Winter Palace to present the Emperor with a petition asking for reforms. Hundreds died on what became known as Bloody Sunday, including many on the snowy Palace Square. Now Nicholas II would return to the scene of these dramatic events, a reluctant reformer whose hand had been forced by an avalanche of events.

The morning was marked by prayer services in most churches. Crowds began gathering along the Neva Embankment to watch as the Emperor and his family sailed past on their way to the Winter Palace. Less royalist crowds also mobbed the avenues leading to the Tauride Palace, to cheer on the new delegates.9 Most conspicuous, though, were the bands of armed police and soldiers. Police and members of the Army were deployed to prevent “stormy meetings, processions and demonstrations with criminal speeches and revolutionary songs.”10 The length of the Neva River was, by order of the Minister of the Interior, was cleared of all vessels from the entrance delta on the Gulf of Finland to the Winter Palace; bridges under which the Emperor would pass were closed to all traffic and manned by armed sentries. Mounted Cossacks patrolled the streets and avenues leading to the Palace, preventing any approach by those who did not carry a special green pass issued for the day. An American observer recorded: “For days before the most elaborate system of coupons and signatures and photographs for identification had been organized with infinite effort to prevent any dreadful occurrence.”11

Rather than a festive atmosphere, St. Petersburg, said one onlooker, “resembled a city prepared to meet an enemy. Everywhere in all the streets soldiers were parading with all kinds of weapons, and so were policemen, some on horse and some on foot, armed with rifles.” Additional bands of mounted Cossacks patrolled outside of factories and universities, always suspected of harboring would-be revolutionaries.”12 Even hospitals were warned to anticipate substantial casualties if disorders erupted in the streets.13

The ceremony at the Winter Palace was scheduled to begin at two that afternoon. As he later told his sister Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna, Nicholas had hardly slept the night before. He had spent the hours tossing and turning, “waking every few minutes with a feeling of sadness and melancholy.”14 Shortly after noon, the Emperor, accompanied by his wife Empress Alexandra; his mother Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna; his brother Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich; and his sister Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna and her husband Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich, all arrived in St. Petersburg by yacht from Peterhof. The men all wore military uniform; having abandoned the original idea of having the ladies arrive attired in Russian court gowns with jewels, the two Empress and the Grand Duchess wore ordinary dresses with jackets and hats; they would change into their formal clothing inside of the Winter Palace.15

After a brief visit to the Cathedral of the Fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul, during which Nicholas prayed at the tomb of his father, the party proceeded to the Winter Palace across the Neva. A guard-of-honor stood at attention as the Imperial Family disappeared into the building. Once inside, Nicholas and his family went to the private apartments, where the ladies were to change. Throughout the early afternoon other Romanovs also arrived at the palace. Approaching the building, Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna the Younger thought it “looked more like a fortress, so greatly did they fear an attack or hostile demonstrations.”16

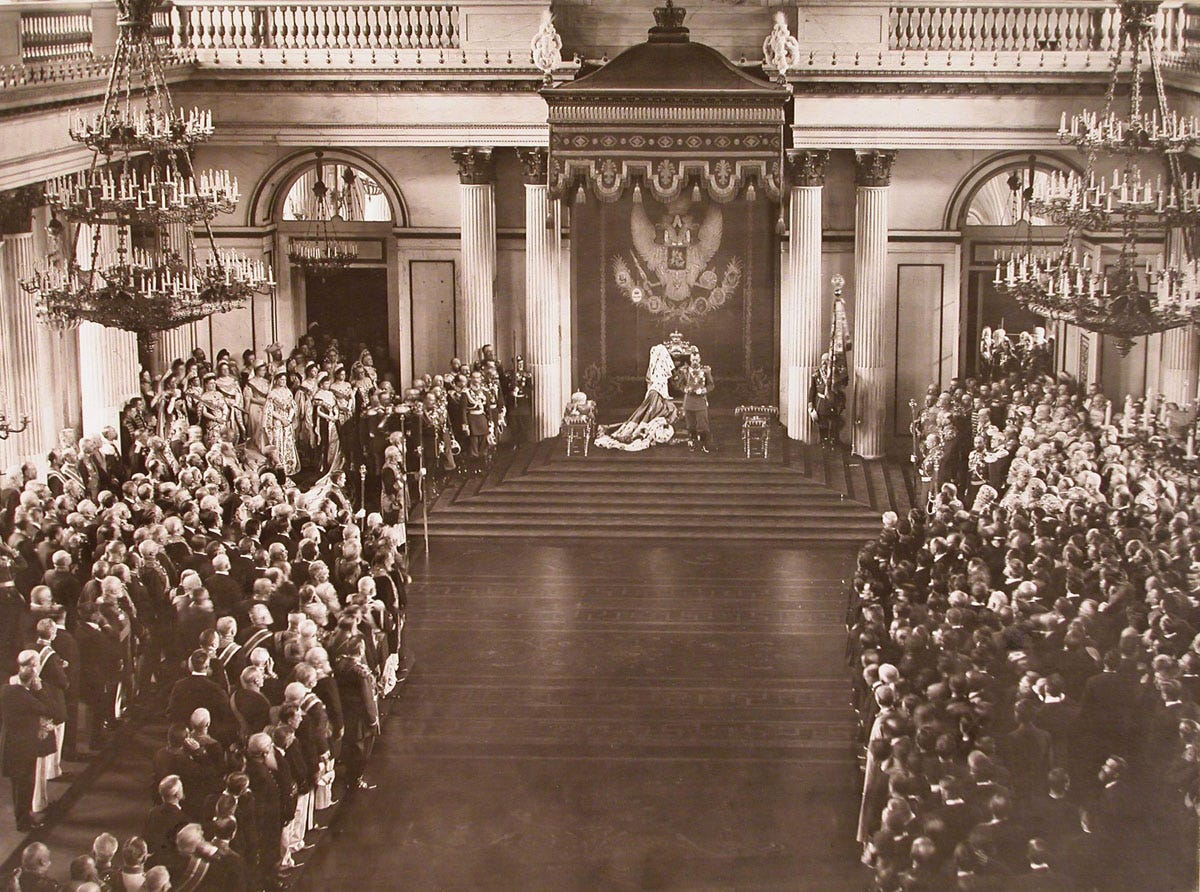

The Hall of St. George, “decorated with gold and crimson hideousness to which all Emperors are obliged to grow accustomed,” as one witness declared, had been carefully prepared for the occasion.17 There was an unfortunate irony here. In this same room, in January 1895, Nicholas II had received congratulations from various rural representative bodies known as zemstvos. The text of these congratulatory addresses had been, as per the custom, sent ahead in advance as a matter of courtesy. In their address, the deputies of the Tver zemstvo asked that they be allowed "to voice their opinion”" on matter involving local governance, “so that the needs of the thoughts…of the whole Russian nation might reach the throne.” This was perceived as a direct threat to the Imperial order, to an autocracy where Nicholas alone ruled, answerable to no one. In his speech to the gathered delegates, the Emperor had warned them not to engage in “senseless dreams” about representation in governmental affairs.18 The Emperor’s speech became legendary, derided by many as tone-deaf and needlessly offensive. And now, eleven years later, in this same room where Nicholas II had warned against the “senseless dreams” about popular representation, he was about to receive the elected delegates to the Duma he had been forced to create.

A young man from Chicago, Samuel Harper had come to Russia to study the country. He supplemented his income by writing occasional articles about his experiences. It took some doing, but he finally managed to convince authorities to grant him press credentials so that he could witness the ceremony. He recalled: “Under instructions, we were in full dress, with tails and white tie, according to the custom of Continental Europe. We all felt very silly, and the British group was particularly annoyed at having to wear evening dress in the morning. We trouped across to the Winter Palace, where, under guard, we were escorted to a balcony in one of the largest reception rooms, which was capable of holding some fifteen hundred people, who later filled it. We were ordered to remain standing and were told not to raise our hands from the sides of our legs. There were guards behind us to enforce the instructions.”19

A regimental band was concealed in the upper gallery of the Hall to play God Save the Tsar when the Emperor appeared; a choir, “all dressed in long cassocks of crimson and gold to match the furniture,” stood on one side of the room.20 Nearby stood “Byzantine bishops and metropolitans in stiff gold and domed miters, who tottered up the space…and embraced each other’s hoary beards with holy kisses.”21 A gold covered table had been erected in middle of the floor. On this stood an icon. The priests, said an onlooked, “found it was so dusty, or had been so much kissed of late, that they had to spend the leisure time in polishing it up with a fairly clean handkerchief.”22

At the end of the room, the crimson velvet throne had been draped “in studied negligence” with the golden Imperial Mantle, lined and edged with ermine; according to rumor, Empress Alexandra herself had arranged the mantle “in artistic folds” to create just the right impression.23 Two gilded stools stood on either side of the throne. “I had hoped to see one of the Tsar’s four little daughters seated on each,” wrote one witness, but they were meant to hold pieces of the Imperial regalia.24

A space was left down the middle of the room, with velvet ropes stretched between short, gilded posts to create an aisle. On the right side of the Hall when facing the throne stood the newly elected deputies to the Duma. One onlooker noted “peasant deputies in high top-boots, with leather belts round their long Sunday coats….in homespun cloth, one Little Russian in brilliant purple with broad blue breeches, one Lithuanian Catholic bishop in violet robes, three Tartar Mullahs with turbans and long grey cassocks, a Balkan peasant in white embroidered coat, four Orthodox monks with shaggy hair, a few ordinary gentlemen in evening dress, and the vast body of the elected in the clothes of every day.”25 One official recalled “one could see a few provincial lawyers or doctors in evening dress…but that which predominated was not even the simple dress of the bourgeois, but rather the long caftan of the peasant or the factory-workman's blouse.”26 Vladimir Gurko, then Assistant Minister of the Interior, thought that the Duma delegates had “dressed in a deliberately careless fashion.”27

One courtier thought that the faces of the deputies were full of “triumphant expressions” on this momentous occasion.28 And another commented: “The faces of the deputies…were lighted by triumph in some cases and in others distorted by hatred, making altogether a spectacle intensely dramatic and symbolical.”29

On the opposite side of the hall stood members of the State Council and the imperial court, in uniforms dripping with gold braid and medals.30 One observer noted members of the Imperial Senate “in brilliant scarlet and gold,” along with “Ministers, with gold lace flowers down their coats, a whole school of admirals, a radiant company of field marshals and generals in blue or white cloth with gold or silver facings and enormous epaulets, and the members of the Holy Synod in their panoply of holiness….Soon the entire side was full of uniforms, and on the breast of each gleamed stars and crosses and medals, a few of which were gained by service in foreign wars. Sometimes one could only hope that the hero would live to win no more distinctions since there was no more room for orders.”31

Alexander Izvolsky, future Foreign Minister, was then serving as a courtier. He remembered “several thousand generals, officers of all ranks, and civil functionaries…resplendent with multi-colored uniforms, glittering with gold and silver lace, and covered with decorations.” Like many of the deputies, these representatives of official Russia did nothing to disguise their feelings: “Here an old general, there a bureaucrat, grown white in the service, could hardly conceal the consternation, the anger even, that the invasion of the sacred precincts of the Winter Palace by these intruders caused him.”32

“A heavy silence prevailed,” one witness recalled. “It was evident at once that between the old and the new Russia a bridge could hardly be built.”33 American George L. Meyer said “The contrast between those on the left and those on the right was the greatest that one could imagine, one being a real representation of different classes of this great empire, the other of what the autocracy and bureaucracy has been.”34 Another witness recorded that the deputies “stood confronting the brilliant crowd across the polished floor, and it was easy to see in them the symbol of the new age which now confronts the old and is about to devour it. Shining with decorations and elaborately dressed in many colors, on the one side were the classes who so long have drained the life of the great nation they have brought to the edge of ruin. Pale, bald, and fat, they stood there like a hideous masquerade of senile children, hardly able to realize the possibility of change. But opposite to them thronged the people, young, thin, alert, and sunburnt, with brown and hairy heads, dressed like common mankind, and striving for the future.”35

At half-past one, members of the Imperial Family gathered in the Malachite Drawing Room. Nearly all members of the Romanov Dynasty were present. “We all wore our full-dress uniforms,” recalled Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich. “Deep mourning would have been more appropriate.”36 Finally they formed into the positions they would take in the procession. Shortly before two that afternoon, a fanfare of trumpets announced the start of the processions: footmen and chamberlains, attired in their golden liveries; masters of ceremony, carrying their maces; members of the Emperor’s Entourage and military suite; and twelve imposing soldiers from the Palace Golden Grenadier Regiment. Officials carried crimson cushions holding the Imperial regalia, which had been brought from Moscow for the occasion: the Imperial Orb, the Imperial Scepter, the State Seal, the Sword of State, the State Banner, and finally the Imperial State Crown.37

The grand masters of ceremonies came next, closely followed, in ascending rank, by the principal dignitaries of the court and members of the military suite. The grand marshal of the imperial court, walking backward and holding his gilded staff of office, preceded the imperial party. Nicholas appeared, wearing the full-dress uniform of the Preobrazhensky Guards Regiment.38 “I had not seen him since the exciting days of the preceding autumn,” recalled Alexander Izvolsky, “and I was struck by his careworn appearance; he looked much older and as if he were deeply moved by the significance of the event.”39

Behind him came the two empresses. Alexandra wore a Russian court dress richly embroidered with intricate foliate designs in gold thread, a tall diamond and pearl kokoshnik holding a long lace veil in place. At her side was the dowager empress, her Russian court dress of white satin edged in sable and another glittering diadem atop her head.40 They had donned diamond necklaces, brooches, and bracelets, “naively believing,” wrote Vladimir Gurko, “that the people’s representatives, many of whom were peasants, would be awed by the splendor of the Imperial Court.” Instead, as he noted, “the effect was altogether different. This oriental method of imposing upon spectators a reverence for the bearers of supreme power was quite unsuited to the occasion. What it did achieve was to set in juxtaposition the boundless Imperial luxury and the poverty of the people. The demagogues did not fail to comment upon this ominous contrast.”41

The Grand Dukes and Duchesses followed, with courtiers, ladies-in-waiting, and adjutants at the rear.42 The procession passed through the ceremonial halls of the Winter Palace. A guard of honor, composed of members of the Chevalier Guards Regiment in their white parade uniforms with red tunics, stood stiffly before the doors leading from the Nicholas Hall to the Concert Hall. The halls were crowded with diplomats, military generals, and lower members of the court; civil officials and delegations of merchants took up positions in the Field Marshal’s Hall, behind serried ranks of His Majesty’s Cossack Konvoi Regiment. Lesser members of the court, various officials, and invited guests were confined to the Peter the Great Throne Room, the Hall of Armorial Bearings, and the 1812 Military Gallery.

As the Imperial procession reached the Hall of the Order of St. George, the musicians in the gallery struck up God Save the Tsar and the robed choir took up its strains. Nicholas walked to the front of the Hall. One witness thought that the Emperor had “a timid swagger in his gait.”43 He stopped before the makeshift altar and kissing the cross offered by Metropolitan Anthony of St. Petersburg. Anthony, along with the Metropolitans of Moscow, Vladimir, and Kiev as well as the gathered bishops and clergy celebrated a Te Deum.44 “The Grand Dukes,” recorded one witness, “came in two or three rows of repeated splendor. With voices of thunder and voices from the tomb, the priests chanted, and called, and read the golden book as only Russian priests are able, and the rows of crimson choir sang the wailing responses between. Upon the right the flashing crowd was busy bowing and signing the cross. Rarely is such religious zeal to be witnessed as the Grand Dukes displayed in crossing themselves; for in this evidence of sanctity they surpassed the very bishops. But the stiff-necked generation on the left remained unmoved. One or two peasants crossed themselves as they were accustomed; a few more complied when the priest shook the solid cross threateningly in their direction; but the black phalanx stood unmoved, polite but detached spectators of these curious survivals.”45

At the end of the brief service, Nicholas slowly crossed the hall and, “slowly and majestically,” in the words of Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, ascended the dais, taking his place on the throne and leaning slightly against the left arm.46 Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna the Younger recalled that the Emperor, “ordinarily able to hide his feelings, was sad and nervous.”47 And Sergei Witte later wrote that the Emperor had looked “quite pale and solemn, but calm.”48

The Empresses, Grand Dukes and Duchesses, and courtiers walked to the side of the hall where members of the Senate stood, crowing in together in a glittering, bejeweled mass. Baroness Buxhoeveden, catching sight of Empress Alexandra, thought that she “looked tragic. Her large, sad eyes seemed to foresee disaster, and her face became alternately red and pale. Her knuckles as she clutched her fan were quite white, she gripped it so tightly.”49 Princess Elizabeth Naryshkina-Kuryakina noted that the Empress “looked depressed,” while Marie Feodorovna seemed “serious, as always.”50 Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich wrote: “I was told by my friends that they noticed tears in the eyes of the Dowager Empress and of Grand Duke Vladimir. I myself would have cried had it not been for a peculiar feeling that came over me when I saw burning hatred in the faces of some of the parliamentarians. I thought they were a queer lot and that I should watch Nicky carefully lest one of them should attempt to come too close to him.”51

Minister of the Imperial Court Count Vladimir de Freedericksz ascended the dais and handed Nicholas the paper containing his speech. The Emperor stood and read:

“Concern for the welfare of our native land, which divine providence has entrusted to me, has prompted me to call upon the peoples elected representatives to assist in the legislative process. With an ardent belief in the brightness of Russia’s future I welcome you the best people whom the nation at my bequest has elected to speak in its behalf. Difficult and complicated tasks lie before you. I believe that love for our motherland and a sincere desire to serve her will inspire and unite you. For my own part I hall protect as immutable the course that I have set. I do so in the firm conviction that you will devote all your strength in selfless service to the nation so as to clarify the needs of the peasants who are so dear to my heart and to identify those things necessary for the enlightenment and welfare of the people while always bearing in mind that the spiritual greatness and prosperity of our land requires not only freedom but also order based on law. I pray that my earnest desire to see my people happy and to pass on to my son the inheritance of a strong, orderly and enlightened state shall come to pass. I pray that the lord will bless the work which awaits me together with the state council and the state duma. May this day signify the renewal of Russia’s morality, may it mark the rebirth of Russia’s best forces. May you approach with reverence the task to which I have summoned you. May you justify the confidence which the tsar and his people have placed in you. God help me and you.”52

The Emperor’s speech had been a headache for officials charged with writing it. Faced with this unprecedented development, courtiers and government officials struggled over both content and tone. In the end, the final draft had been written by V. I. Kovalevskii based on a draft provided by General Dmitri Trepov, Assistant Minister of the Imperial Court and Court Commandant.53 As historian Abraham Ascher wrote, “The address they finally produced was so vague as to suggest a lack of serious interest in the work of the Duma. It did not include a single proposal for reform, and this was bound to offend even the moderate deputies. After all, the legal and peaceful reform of Russia’s political, economic, and social institutions was a primary reason for the establishment of a legislature in the first place. Nicholas confined himself to words that appeared to be gracious and generous but in fact did not in any way meet the concerns of the liberals and the moderate left, not to mention the radicals.”54

Members of the Imperial Family and the court were nearly unanimous in their descriptions of the Emperor’s delivery. His brother-in-law Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich thought that Nicholas “read it well, in a clear, resounding voice, controlling his emotions and concealing his sorrow.”55 Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna wrote: “He spoke so well, saying just what was needed, asking everyone to come to his aid.”56 Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich recorded that the Emperor “loudly, distinctly and slowly began to read the speech. The more he read, the more he read, the more strongly I was overcome by emotion. Tears flowed from my eyes. The words of the speech were so good, so truthful and sounded so sincere that it would have been impossible to add anything or to take anything away.”57 And Alexander Izvolsky wrote that the Emperor “read his address in a rather low voice, but without embarrassment or hesitation, articulating each word distinctly and emphasizing a phrase here and there. The discourse of the Emperor was listened to with the greatest attention and in perfect silence.”58

Several of the Duma leaders were also suitably impressed. “The Emperor is a true orator,” said one, adding that “his voice is extremely well modulated.” And Feodor Rodichev, one of the leaders of the Constitutional Democratic Party, recalled: “It was a well written speech. It was read beautifully with correct emphasis with full understanding of ach phrase, clearly and sincerely.”59

But the reaction from most of the delegates was muted – “a heavy silence prevailed,” said one onlooker. “It was evident at once that between the old and the new Russia a bridge could hardly be built.”60 “The shouts of ‘hurrah,’ vociferous on the side of the Imperial Council,” recalled Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich, were “perfunctory in the section reserved for the Duma.”61 Alexander Izvolsky wrote: “In spite of the good impression produced by the address, it was not greeted with any applause at the close” from the delegates, although he attempted to explain this away by ascribing it to “the restraint to which the deputies were subjected by an atmosphere and surroundings that were so strange to them.”62 After noting that the speech “could hardly be called one of welcome,” Samuel Harper that “the Duma group representing the new Russia showed its disappointment by the restraint of its applause.”63

American onlooker Henry Nevinson recorded of the Emperor’s speech:

“All knew that a turning-point in history had come, and that to this little man one of the world’s great opportunities had been offered. But with every sentence that was pronounced, the hopes of the new age faded. As commonplace succeeded commonplace, amid the usual appeals to Heaven and the expression of such affection as monarchs always feel for their subjects, it was seen that no concession was made, no conciliation attempted…. When the end came, and the colors were waved, and the band played, and the officials shouted, ‘Hurrah!’ as the Imperial procession marched from the hall, the members of the party of progress stood dumb. They knew now that for the future they had only themselves to look to, and that the greatest conflict of all still lay before them.”64

One deputy later said that the silence “was the natural expression of our feelings towards the monarch, who in the twelve years of his reign had managed to destroy all the prestige enjoyed by his predecessors.65 Alexander Izvolsky noted that the faces of the deputies “were lighted by triumph in some cases and in others distorted by hatred, making altogether a spectacle intensely dramatic and symbolic.”66 Count Vladimir de Freedericksz complained: “The deputies? They give one the impression of a gang of criminals who are only waiting for the signal to throw themselves upon the ministers and cut their throats! What wicked faces! I will never again set foot among those people.”67

The silence, and the looks on the faces of many of the deputies, thoroughly unnerved members of the Romanov Dynasty. “The majority of them wore a lugubrious aspect,” recalled Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna the Younger. “It was easy to believe yourself at a funeral.”68 “I remember the large group of deputies from among peasants and factory people. The peasants looked sullen. But the workmen were worse: they looked as though they hated us. I remember the distress in Alicky’s [Empress Alexandra’s] eyes.”69 In her diary Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna mentioned “several men with repulsive faces and insolent, disdainful expressions. They neither crossed themselves nor bowed but stood with their hands behind their backs or in their pockets, looking somberly at everyone and everything.”70 And the Dowager Empress complained that “those dreadful deputies” had “closed their mouths while everyone else shouted ‘Hurrah!’ I saw that full well.”71 She later confessed that she had been “shocked” to see so many “commoners” in the palace. “They looked at us as upon their enemies and I could not stop myself from looking at certain faces, so much did they seem to reflect a strange hatred of us all!”72

Once the ceremony had ended, the Emperor and members of the Imperial Family returned to the private apartments. Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna recorded: “Mama and Alix were crying, and poor Nicky was standing there in tears – his self-control finally overcome, he could not hold back the tears.” When they left the palace to return to Peterhof, she noted that “the public gave us a warm welcome as we walked along the embankment with Nicky, Mama, and Alix to get into our carriages. There was a huge cheer. Some men, standing on a pedestal, shouted in a loud voice, ‘Thank you, Your Majesty!’ Children and adults were standing on the balconies and at the windows of the Winter Palace, also cheering, waving their handkerchiefs, greeting us.”73

That night, after returning to Peterhof, Nicholas II sat down and as was his habit, made an entry into his diary. Noting that it was “a significant day,” he made no mention of the reaction to his speech. His only comment was that his heart “was light, after the ceremony had come to a successful end.”74 Others, though, were more disturbed. Princess Elizabeth Naryshkina-Kuryakina, one of Empress Alexandra’s ladies-in-waiting, took tea with Princess Marie Golitsyna, Alexandra’s Mistress of the Robes. The elderly Princess Golitsyna, she recalled, “told me that at that moment she had the feeling that something great was crashing – as if all Russian tradition had been annihilated in a single blow.”75 Courtier Alexander Mossolov later wrote: “I am convinced that the throne room ceremony, with dignitaries covered with gold braid and decorations, merely filled the deputies with envy and hatred. It certainly did not succeed in restoring the prestige of the Sovereign as had been hoped. The deputies seemed to me to be incapable of collaborating with the Government; they produced the effect of enemies engaged in an internecine struggle with it for the upper hand.”76 Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich later succinctly called the day “the funeral of the regime.”77

Once the ceremony had ended, the delegates left the Winter Palace to make their ways to their first sitting at the Tauride Palace. They traveled either by carriage through the streets or by motor launches along the Neva. “Along both routes between the two palaces,” wrote historian Ann Healy, “the new legislators were to pass excited throngs, which had come out into the bright spring sunshine to view them. People lined the bridges, streets, and riverbanks, while at two points along the Neva, prison inmates waved white handkerchiefs from cell windows and called to the deputies sailing past below. The street crowds took up their cry and the demand for an amnesty filled the air. Thus, the people’s elect entered the assembly chambers with this din still in their ears and the white flags of the incarcerated still waving before their eyes.”78

Russia’s new Duma lasted a mere seventy-two days. It wanted political amnesty, expropriation of land, and ministers responsible to the parliament. None of this, of course, went over well with the Emperor, who rejected such ideas out of hand. When the Duma began investigating the government’s possible complicity in pogroms against Russia’s Jewish subjects, it proved to be the final straw. Nicholas had the body closed, declaring that new elections to a second Duma were to shortly take place. These, too, provided a body filled with less than compliant voices, and once again the Emperor shuttered the legislature. Before elections for the Third Duma took place, he illegally altered the laws to ensure more conservative representatives.

Increasingly Nicholas came to view the Duma as an unwelcome reminder of a decision he believed had been forced upon him. It had been birthed through extortion, and multiple times the Emperor explored either reducing the legislature to a purely consultative body or eliminating it altogether. At times he worked with its members, giving way to some of their demands only to reject others. He did his best to treat the Duma as Russia’s bastard stepchild. Only once, on February 16, 1916, did he set foot in the Tauride Palace to speak to the members, and then only because Rasputin had advised that he do so to appease public opinion.79 Just a year later, Rasputin was dead, and Nicholas II would be forced to abdicate his throne.

There is a coda of sorts. Aware of the importance of the occasion, the Imperial Court allowed a St. Petersburg newsreel cameraman, A. K. Yagelsky, to set up his equipment in the gallery of the Hall of the Order of St. George so that he could film the scene. Although his footage is fragmented, it amazingly survives and has been restored. Two segments exist. The first shows the Emperor and the two Empresses entering the hall and kissing the cross held by Metropolitan Anthony, followed by members of the Imperial Family and courters. The wide space left in the middle of the Hall is clearly visible, with the Duma deputies gathered on the left side of the footage and representatives of official Russia on the right. The second segment shows Nicholas II reading his speech.80 It is, of course, silent, but together these reels offer us a rare glimpse at what proved to be one of the most momentous events of Nicholas II’s reign.

The footage can be seen here:

The entrance to the Hall:

https://www.facebook.com/PageRomanovNews/videos/895240954257600/

The speech:

https://www.facebook.com/PageRomanovNews/videos/563761191011121/

Source Notes

1. Verner, 300-01.

2. Figes, 213.

3. Ascher, 82; Izvolsky, 74.

4. D’Encausse, 110.

5. Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, diary entry of April 19, 1906, in Maylunas and Mironenko, 292.

6. Ibid., diary entry of April 21, 1906, in Maylunas and Mironenko, 292.

7. Nevinson, 316.

8. Healy, 150.

9. Romanov News, No. 146, May 2020; Figes 213.

10. Ascher, 82.

11. Nevinson, 319-20.

12. Ascher, 82.

13. Nevinson, 316.

14. Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna, diary entry of April 27, 1906, in Maylunas and Mironenko, 293.

15. Alexander Mikhailovich, 211.

16. Marie Pavlovna, 84.

17. Nevinson, 320.

18. Izvolsky, 255

19. Harper, 35.

20. Figes, 213; Nevinson, 321.

21. Nevinson, 323.

22. Ibid., 320.

23. Ibid.; Gurko, 470.

24. Nevinson, 323.

25. Harper, 321-22.

26. Izvolsky, 75.

27. Gurko, 470.

28. Naryshkina-Kuryakina, 189.

29. Izvolsky, 76.

30. Oldenburg, 2:199.

31. Nevinson, 320-21.

32. Izvolsky, 75-76.

33. Healy, 149.

34. Ascher, 83-84.

35. Nevinson, 322.

36. Alexander Mikhailovich, 211.

37. Oldenburg, 2:199; Mossolov, 138.

38. Oldenburg, 2:199.

39. Izvolsky, 77.

40. Lieven, 159.

41. Gurko, 470.

42. Oldenburg, 2:199.

43. Nevinson, 323.

44. Lieven 159; Romanov News, No. 146, May 2020.

45. Nevinson, 324.

46. Lieven, 159; Oldenburg, 2:199.

47. Marie Pavlovna, 84.

48. Witte, 603.

49. Buxhoeveden, 276.

50. Naryshkina-Kuryakina, 189.

51. Alexander Mikhailovich, 212.

52. Oldenburg, 2:200; Novoe Vremya, April 28, 1906.

53. Witte 603.

54. Ascher, 84.

55. Alexander Mikhailovich, 213.

56. Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna, diary entry of April 27, 1906, in Maylunas and Mironenko, 293.

57. Lieven, 159.

58. Izvolsky, 77.

59. Oldenburg, 2:200.

60. Healy, 149.

61. Alexander Mikhailovich, 213.

62. Izvolsky, 78.

63. Harper, 35.

64. Nevinson, 324-25.

65. Figes, 214.

66. Izvolsky, 74-76.

67. Mossolov, 139.

68. Marie Pavlovna, 84.

69. Vorres 121.

70. Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna, diary entry of April 27, 1906, in Maylunas and Mironenko, 293.

71. Healy, 151.

72. Figes, 214.

73. Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna, diary entry of April 27, 1906, in Maylunas and Mironenko, 293.

74. Nicholas II, diary entry of April 27, 1906, in D’Encausse, 110.

75. Naryshkina-Kuryakina, 189.

76. Mossolov, 140.

77. Alexander Mikhailovich, 213.

78. Healy, 152.

79. Ibid.

80. Romanov News, No. 146, May 2020.

Bibliography

Alexander Mikhailovich, Grand Duke. Once a Grand Duke. New York: Farrar, 1933.

Ascher, Abraham. The Revolution of 1905: Authority Restored. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994.

Buxhoeveden, Baroness Sophie. Before the Storm. London: Macmillan, 1938.

D’Encausse, Helene Carrere. Nicholas II: The Interrupted Transition. New York: Holmes & Meier, 2000.

Figes, Orlando. A People’s Revolution. London: Random House, 1997.

Gurko, Vladimir. Features and Figures of the Past: Government and Opinion in the Reign of Nicholas II. Stanford: Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace, 1939.

Harper, Samuel N. The Russia I Believe In. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1945.

Healy, Ann. The Russian Autocracy in Crisis, 1906-1907. Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1976.

Izvolsky, Alexander. Recollections of a Russian Foreign Minister. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1921.

Lieven, Dominic. Nicholas II. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1994.

Marie Pavlovna, Grand Duchess of Russia. Education of a Princess. New York: Blue Ribbon Books, 1931.

Maylunas, Andrei, and Sergei Mironenko. A Life Long Passion. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1994.

Mossolov, Alexander. At the Court of the Last Tsar. London: Methuen, 1935.

Naryshinka-Kuryakina, Princess Elizabeth. Under Three Tsars. New York: Dutton, 1933.

Nevinson, Henry W. The Dawn in Russia, or Scenes in the Russian Revolution. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1906.

Novoe Vremya.

Oldenburg, S. S. Nicholas II, His Reign & His Russia. 4 volumes. Gulf Breeze, FL: Academic International Press, 1977.

Romanov News, published by Paul Kulikovsky, No. 146, May 2020.

Verner, Andrew M. The Crisis of Russian Autocracy: Nicholas II and the 1905 Revolution. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Vorres, Ian. The Last Grand Duchess. London: Hutchinson, 1965.

Witte, Sergei. The Memoirs of Count Witte. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1990.