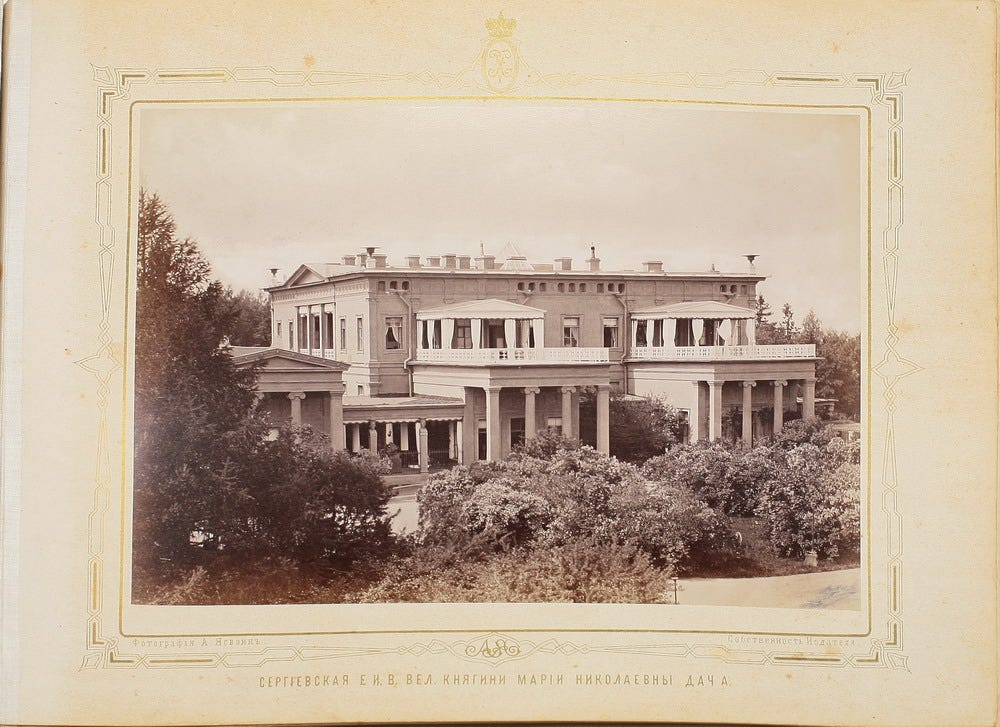

It would have been better for Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaievna, Nicholas I’s eldest daughter, had she been born a man. She was headstrong, imperious in manner, domineering, and flagrant in her love affairs. Such behavior by a Grand Duke could have swept aside or overlooked; in a Grand Duchess, it led to scandal, isolation, and unhappiness. Luckily for the Imperial Court, much of the drama played out in Sergievka, a fashionable, severely Grecian-style villa on the edge of the Gulf of Finland and not in St. Petersburg.

The estate stretched from the St. Petersburg Highway along the crest of the hill down to the shore of the Gulf of Finland, between Oranienbaum and Peterhof. Various owners had previously occupied the site. One plot belonged to Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich, son of Peter the Great; after his death, it passed to his son, the future Emperor Peter II. Other portions were owned by the Dolgoruky family, and Field Marshal Peter Rumyantsev-Zadunaisky, for whose son Sergei the estate was named in 1790. In 1822, the family sold their part of the estate to Kirill Naryshkin, who laid out an extensive park around the wooden manor house.1

In 1838, after Naryshkin’s death, Nicholas I purchased the estate from his heirs for 560,908 rubles and gave it to his daughter Maria Nikolaevna as a wedding present, “for her eternal and hereditary possession.”2

Born in 1819, Maria Nikolaevna grew up at Anichkov Palace, Gatchina, Peterhof, and the Winter Palace. Educated by a series of governesses and then by poet Vasili Zhukovsky, she was an intelligent if willful pupil, with a talent for music, painting, and a love for the arts. Maria could be mercurial in mood, alternately charming and gracious and then selfish and stubborn. Nicholas made little secret of the fact that Maria was his favorite child, and he doted on her, indulging her whims and moods. Even as a young woman, renowned for her beauty, she tended to scandalize society, smoking cigars and flirting outrageously with handsome young officers.

In 1837, Maria met Maximilian, Duke of Leuchtenberg during a visit to Bavaria. A few months later, he came to Russia to take part in military maneuvers and the acquaintance was renewed. Maria was smitten. Max was handsome, educated and shared Maria’s interest in the arts. His uncle was King Ludwig I of Bavaria. All well and good, a suitable husband – but not for a Russian Grand Duchess and the Emperor’s eldest daughter. He wasn’t a prince; worse yet, he was a son of Eugène de Beauharnais, making him a grandson of Empress Josephine. As a mere Duke he carried the style of Serene Highness. He also happened to be Catholic. Everything seemed to conspire against such a match, but Maria was determined. Nicholas I finally agreed to the union on the condition that Max would move to Russia and remain there, and that any children born into the marriage would be raised in the Orthodox Church. The wedding took place in the Cathedral of the Winter Palace on July 2, 1839. Nicholas I granted Max the style of His Imperial Highness and issued an edict granting any children the title of Prince or Princess Romanovsky. They were to be considered members of the Imperial House, with full succession rights.

The young couple was very much in love, at least in the beginning. Children soon arrived. Maria, born in 1841, later married Wilhelm of Baden. Nicholas, born in 1843, became 4th Duke of Leuchtenberg and later contracted a morganatic marriage. Eugenia, born in 1845, married Prince Alexander of Oldenburg, and was mother of Prince Peter of Oldenburg, who wed Alexander III’s youngest daughter Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna. Eugene, who was born in 1847, managed to best his elder brother Nicholas by contracting two morganatic marriages: his second wife was renowned beauty Zinaida Skobeleva, who carried on a very public affair with Alexander III’s brother Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich. By the time of Eugene’s birth, though, the marriage had faltered. Both Maria and Max pursued their own romantic relationships, and some doubts surround the births of the other two children born into the Leuchtenberg marriage: Sergei, born in 1849 and who was killed in the Russo-Turkish War, and George, born in 1852, and who later married Princess Anastasia of Montenegro. Both Sergei Witte and Alexander Polovtsev, intimates of the Imperial Court who heard and recorded the gossip that came their ways, believed that these two sons were fathered by Maria’s last lover Count Gregory Stroganov.3

Before the marriage faltered, though, Maria and Max focused their energies on two residences. In St. Petersburg, architect Andrei Stackenschneider built the enormous Mariinsky Palace on St. Isaac’s Square for the couple, and on the Gulf of Finland they asked him to design and build a summer residence. Stackenschneider’s plans drew on the work of Prussian architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel, and specifically his original design for the Palace at Oreanda in the Crimea for Empress Alexandra Feodorovna (which was abandoned owing to its immense cost) and his Glienicke Palace at Potsdam. Those plans were executed according to neoclassical designs, but more specifically drew in elements of ancient Greek and Roman architecture. The dacha copied elements found in Roman villas, lending the building a unique feel when compared to the string of Baroque, rococo, Gothic, and Italianate villas and palaces lining the shore of the Gulf of Finland.4

Construction began in 1839 and was completed in November 1842. Stackenschneider wrapped the buff-colored facades in a variety of Hellenic details: columned peristyles extended at the ends, enclosing terraces; balconies were ringed with classical balustrades and plinths set with urns and statuary; long colonnades linked the main, two-storey structure to flanking pavilions; and loggias lined with Corinthian columns.5 It looked very much like a Grecian villa, with elements of a Roman temple – like the pediments and cornices – deployed for architectural interest.6

The interior continued the Grecian theme, while mixing in elements from Roman villas and the ruins discovered in Pompeii. The dacha centered on a magnificent, two-storey center hall resembling an atrium, ringed by columns and rising to a skylight that flooded the room with light. Stackenchneider designed the main rooms with elaborate cornices, door and window frames, and stucco decoration. A. Andreev, S. Davydiov, I. Drolinger, and I. Tabarin were brought in to painted inset wall panels with classical figures and vases in black and gold against red and blue backgrounds. Special suites of furniture of Karalian birch, adorned with gilded cherubs and mythological figures, were commissioned from the St. Petersburg firm of Heinrich Gambs. Rooms were filled with the copies vast array of paintings and classical sculptures. The Grand Duchess’s private apartments included a boudoir, a bedroom, a dressing room, and a bath with sunken tub; a narrow staircase linked them to the rooms of her husband on the floor above.7

Stackenschneider also designed the adjacent service buildings, including the Kitchen and the Hofmeister’s Block. He built a tea house along the side of the meadow, as well as the Church of the Holy Martyr Tsaritsa Alexandra to the south of the palace, erected in 1846 in memory of the Grand Duchess’s young daughter Alexandra, who died from whooping cough as a young girl.8

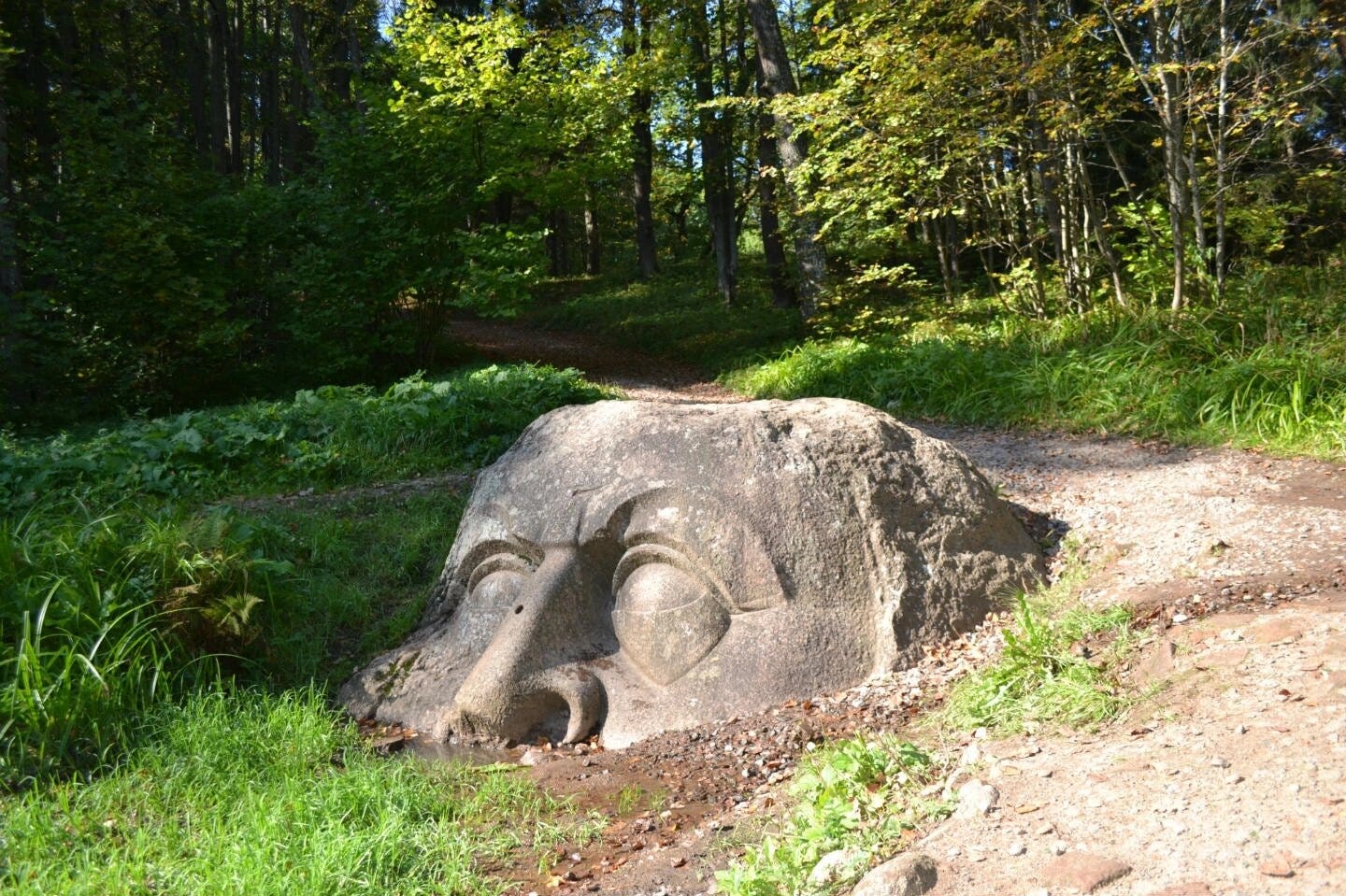

Surrounding the dacha was a formal garden, with elaborate parterres filled with roses and dotted with statuary and splashing fountains. Beyond lay a landscaped park, designed in the English manner by Peter Erler in the 1820s. The Kristatelka River, which flowed along the upper edge of the property, was diverted and dammed to form ponds, streams, and cascades that offered a picturesque touch. Groves of fir, spruce, oak, birch and aspen trees circled open meadows planted with wildflowers. In one corner of the park was its most famous feature, a giant sculpted half-head of granite, sunk into the grass. Little is known about its origin, with various theories put forth as to its creation, but the truth remains lost. But it has been suggested that this inspired the head appearing in Pushkin’s poem Ruslan and Lyudmila.9

Max developed tuberculosis after an expedition to the Urals, and on his return to St. Petersburg he fell increasingly ill. On November 1, 1852, he died. Maria Nikolaevna waited just a year to secretly marry her long-term lover Count Gregory Stroganov. On November 13, 1853, she wed Stroganov in a private ceremony in the Chapel of the Mariinsky Palace in St. Petersburg. The union was kept secret even from her father.

After Nicholas I’s death in 1855, Alexander II granted retroactive approval for the marriage, which was morganatic, but this came with conditions. The union was still to be considered secret; if Maria became pregnant, she was “obliged to retire for the duration of childbirth from the capitals and other places of residence of the Imperial Family. Count Gregory Stroganov may have a place in the St. Petersburg and country palaces of Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna, but not otherwise than by virtue of his rank numbered in Her Court. He must not appear with her as her spouse, neither in the family nor in any other meetings of our House or Court, nor in any public place, or in general before witnesses. He can allow himself to walk with the Grand Duchess only in Her Highness's own gardens in St. Petersburg and at Sergievka, but by no means in Peterhof, and other Imperial gardens, where they could meet with walkers or passers-by.”

Two children were born of this second marriage, Count Gregory in 1857, and Countess Elena in 1861. The boy died at the age of two, while Elena died in 1908. Finding the restrictions imposed on her marriage too restrictive, Maria left Russia, settling with Stroganov in Europe. But this marriage, like her first, soon unraveled, and the Grand Duchess eventually moved to Florence, where she spent her days amassing an immense collection of paintings, sculpture and furniture. She would periodically return to Russia and it was in St. Petersburg that, on February 21, 1876, she died at the age of fifty-six. Stroganov survived her by three years, dying in 1879.

After the Grand Duchess’s death, Sergievka was inherited by her youngest son George, who became the 6th Duke of Leuchtenberg on the death of his brother Eugene in 1901. His first wife, Princess Theresa of Oldenburg, died in 1883, having given birth to a son, Alexander, in 1881. In 1889, George married again. His second wife was Princess Anastasia of Montenegro, whose sister Militsa married Grand Duke Peter Nikolaievich that same year. The couple had two children, Sergei, born in 1980, and Elena, born in 1892, but the marriage was unhappy. George ignored his wife in favor of his mistress, much to the anger of Alexander III.

With George often away in France, Anastasia became the mistress of Sergievka, and it was now that the estate assumed a sinister aura in the imaginations of the Imperial Family and the Court. Together with her sister Militsa, Anastasia began introducing a succession of highly questionable “holy men” to Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, often at Sergievka, including Philippe Nazier-Vachot. This reached its climax on November 1, 1905, when Nicholas and Alexandra visited Sergievka and were first introduced there to Gregory Rasputin.

George and Anastasia divorced in 1906; the following year she married Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaievich, Jr. After George’s death, the villa passed to his son Alexander, who became the 7th Duke of Leuchtenberg. He was the last Imperial owner of the estate. Following the Revolutions of 1917, Sergievka was appropriated by the state. The park was opened to the public and eventually the dacha was given to the Biological Research Institute of the University of Leningrad.

During World War II, Sergievka found itself on the front line of the Nazi approach to Leningrad. The villa was struck by artillery, and the interiors were destroyed in subsequent fires. In 1965, Leningrad architect V. I. Zeidemann restored the walls and roof to the original lines, though no attempt was made to recreate Stackenschneider’s original interiors. Instead, the spaces within were divided into offices and laboratories for continued use by the Biological Research Institute, which continues to occupy the building. It remains closed to the public.10

Source Notes

1.http://www.purlieus.ru/palace.htm;

https://xn--c1acndtdamdoc1ib.xn--p1ai/kuda-shodit/mesta/dvortsovo-parkovyy-ansambl-sergievka/; Borisova, 265.

2. http://www.purlieus.ru/palace.htm; Borisova, 265.

3. Witte, 177.

4. Borisova, 266.

5. http://www.purlieus.ru/palace.htm.

6. Borisova, 266-67.

7. https://xn--c1acndtdamdoc1ib.xn--p1ai/kuda-shodit/mesta/dvortsovo-parkovyy-ansambl-sergievka/; http://www.purlieus.ru/palace.htm; Borisova, 267-68.

8. http://www.purlieus.ru/palace.htm.

9. http://www.purlieus.ru/palace.htm; http://www.ecosafe.pu.ru/RB/Sergiev/sermain.html; https://xn--c1acndtdamdoc1ib.xn--p1ai/kuda-shodit/mesta/dvortsovo-parkovyy-ansambl-sergievka/; Borisova, 268.

10. http://www.purlieus.ru/palace.htm; https://xn--c1acndtdamdoc1ib.xn--p1ai/kuda-shodit/mesta/dvortsovo-parkovyy-ansambl-sergievka/; Borisova, 268-69.

Bibliography

Borisova, E. A. Russkaya arkhitektura v epokhu romantizma. St. Petersburg: Dmitriy Bulanin, 1999.

Witte, Count Sergei. The Memoirs of Count Witte. Edited by Sydney Harcave. Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe, Inc., 1990.

Internet Sites

http://www.purlieus.ru/palace.htm

https://xn--c1acndtdamdoc1ib.xn--p1ai/kuda-shodit/mesta/dvortsovo-parkovyy-ansambl-sergievka/