Semyon Semyonovich Fabritskii: "The Most Precious Memories of My Life..."

Part 5: Continued Annotated Excerpts from "Memoirs of the Fligel-Adjutant to Nicholas II."

PART V

Fabritskii picks up his narrative by reflecting on his Court service and especially on the characters of Nicholas II and his family:

“Having lived in Livadia from October 15 to December 9, being in continuous communication with Their Majesties and observing them at different times and under different circumstances, I managed to form a clear idea of their characters. The time will come when an impartial historian will pay tribute to the Tsar-Martyr and his long-suffering Family, who laid down their lives for their people. In my memoirs, I only want to give the most truthful description of what I saw and heard.

“Sovereign Emperor Nicholas II had an even, calm character, and at the same time he had a rare self-possession and was very well-mannered. This combination produced an impression on people who were little acquainted with His Majesty, as it were, that he had a gentle and weak character. In the most difficult moments of his reign, in the endlessly difficult moments of the illness of his spouse or children, His Majesty always kept his composure and seemed complete calm, which many explained by alleged heartlessness.

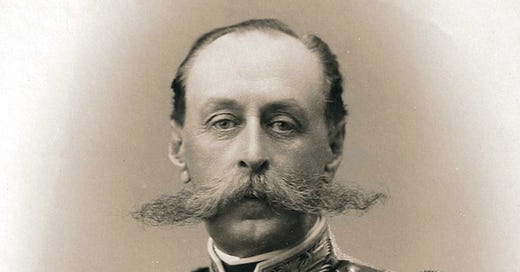

“The kindness and justice of the Sovereign was extraordinary. Always and with all decisions, His Majesty was guided by the desire not to offend anyone, even if by accident, which is why he almost never made quick decisions. This gave rise to rumors about his indecision and his dislike for people of a decisive character. As evidence to the contrary, I can give an example of the Sovereign's uninterrupted, even relations with such people as Baron Freedericksz; Count Benckendorff; Adjutant-General Vannovsky; Adjutant-General Lomen; Major-General Vladimir Orlov (1); Adjutant-General Dubasov; Adjutant-General Grigorovich; General Dumbadze, and others. All of these personalities, who played a prominent role in the reign of the Sovereign, had exceptional, resolute characters and at the same time always enjoyed the trust and respect of their Monarch.

“As an exceptionally educated person, the Emperor did not understand and did not allow rudeness, noisy disputes, or insults that characterize so many harsh people. Hence the rumor began that the Sovereign did not like to hear the truth and that ministers and people close to him did not dare to speak truthfully for fear of falling out of favor. This is absolutely wrong, since His Majesty did not like false or servile people or flatterers, and generally did not allow the possibility of lying, since he himself was absolutely not capable of any slightest falsehood or lie. People who were sharp, who thought about themselves, who thought to save Russia with rude and harsh truths, who were very one-sided and suspicious, received cold rebuffs from the Sovereign for their inappropriate and tactless antics or speeches, then had the audacity to spread rumors about the Sovereign's dislike for the truth.

“I do not admit the possibility that such outstanding personalities as Minister of War Vannovsky; Naval Admiral Grigorovich; the Ober-Procurator of the Synod Pobedonostsev (2); the Chairman of the Council of Ministers Solypin (3); and many others of the same sort ever allowed themselves to tell the Sovereign a lie, which, however, did not prevent them from enjoying the full respect and trust of the Sovereign to death.(4) And vice versa, such personalities as S. I. Witte; Admiral Alekseev (5); Chairman of the State Duma Rodzianko (6), and many, many others were unfortunately false; they did not always avail themselves of telling the truth, and trying to play several sides naturally did not find sympathy with the Sovereign, although he had, reluctantly, to use their services, as people of talent and statesmanship were not so easy to find among the mass of Russian people.

“As a vivid example of the Sovereign's love for decisive and truthful people, I will give an example of His Majesty's attitude towards the only person close to him and – I think – only real friend, General Alexander Orlov. Those who knew him can confirm that this bright personality, this warrior who operated without fear or reproach and was devoted to his Monarch without resorting to flattery, was was incapable of telling a lie and possessed an exceptionally resolute character which, with his talents, gave him the opportunity to make such a brilliant, well-deserved career.

“Once, General Orlov and I were invited to an evening at Anna Vyrubova's. Soon Their Majesties arrived. Met by the hostess of the house in the hallway, Her Majesty went into the inner rooms, and the Sovereign entered the drawing room where we were. It was impossible not to notice that the Sovereign was somehow very preoccupied, upset about something. After greeting us, the Sovereign sat down and immediately shared his grief, saying that he had recently received a report that one of the companies of the Brest Infantry Regiment, brought out for drill, had killed its officers and, under the influence of agitators, had the intention of leading the entire regiment to revolt. There was an involuntary pause, because such a sad and unheard-of news in those days could not but have a depressing effect on us. Before we had time to answer anything, the Sovereign turned to General Orlov with the question, 'Alexander Afinogenovich, what do you think should have been done with this company?' To this, General Orlov answered in a loud and clear voice: 'We need to shoot the whole company down to every last person.' It was hard to imagine a more decisive answer. The Sovereign Emperor thought a little and answered, 'Yes, perhaps you are right.'

“In reality, of course, what was done was according to the law: an investigation began, which dragged on for an infinitely long time, and during which there were many cases of the murder of officers and riots in military units. This, of course, would not have happened if, due to special the importance of the crime, General Orlov's advice, no matter how cruel it was, had been followed.

“The Sovereign was terribly modest, did not like showiness, verbose speeches, any kinds of toasts, ceremonial receptions, or balls. He loved simplicity in everything and preferred quiet family comfort over everything. Therefore, all the stories about the Sovereign's lust for power, about his despotism, about the unwillingness to give up Autocracy for the sake of some personal benefits, are absolutely untrue. If it were not for the sense of duty to the Motherland and the consciousness that he must reign for the benefit of Russia, which he infinitely loved, that he must bear all the burdens of government until the last day of his life, the Sovereign would gladly have transferred the Throne to another person and retired to private life. But he had absorbed a consciousness of duty to the Motherland as an infant took in its mother's milk and, like a sentry on duty, the Sovereign did not consider it possible to abandon his post.

“Not being present personally at the abdication of the Sovereign Emperor Nicholas II from the Throne, I cannot imagine with what arguments and convictions Ruzsky (7), Guchkov (8), and Shulgin (9) convinced him that this was the best solution for the Motherland. How much, apparently, the poor Sovereign had to go through and endure severe disappointments long before that, and most importantly, to lose faith in people and his closest assistants.

“The Sovereign Emperor possessed exceptional patience and was distinguished by amazing indulgence towards his subjects, regardless of their position. The sovereign was terribly industrious. He usually got up at 7 o'clock in the morning (10), took a bath, got dressed and at 8 o'clock was already at prepared, spending almost the whole day until late at night at work. I have already spoken about how the day of the Sovereign was distributed. I will only add that once a week, on Wednesdays, from 11 o'clock to 2 o'clock, the Sovereign Emperor presented himself to various persons who had received some kind of appointment or who had come on vacation from the provinces. All persons from commanders of regiments and those in civil departments had the right to present themselves.

“On these Wednesdays, about 45 people were usually presented to the Sovereign; persons holding high positions were introduced separately, face-to-face, in private offices and the rest in the new offices all at once, although the Sovereign personally greeted everyone, asked questions and listened to the answers. Many times I personally witnessed how amazed those presenting were amazed at the memory of the Sovereign for faces and facts and knowledge of their various trifles....

“Thus passed the days of the All-Russian Emperor, whom the leftist press called 'bloody.' Modestly, imperceptibly, without theatrical effects, the Emperor ruled his country of many millions, selflessly and proudly loving His Motherland. The Sovereign gave all his strength and thoughts to the service of his people, so dearly loved and in whose loyalty the Sovereign never doubted.

“The Sovereign's only consolation and joy was his family, to which he could only give an insignificant part of the day, the hours of breakfast and lunch.(11) All the rest of the time, scheduled to the minute, was given to the fulfillment of his duty to the Motherland and caring for his people. And the Sovereign's consciousness was so heavy that he had no assistants. The people chosen by him cared more about their own welfare or the welfare of their loved ones, and not about the work entrusted to them. Intrigues, tricks, envy, gossip, denunciations, meanness and treason – this is what surrounded the Throne and betrayed him along with the Motherland. And despite the horror of loneliness, despite the firm conviction of the impossibility of trusting the people around him (12), the Sovereign cheerfully, inspired by the infinitely loving and beloved spouse, remained at his post, enabling the people to prosper, grow rich, and be proud of the power and wealth of His Motherland.

“That is why the evil people, seeking to attack the person of the Sovereign and the humiliation of the Motherland, sowed confusion and discord among the Russian nation and so hated Empress Empress Alexandra Feodorovna.

“After the Motherland and his Family, the Emperor most of all loved the army and navy. The reports of the military and naval ministers were always pleasing to him. With particular willingness, the Sovereign devoted time to reviews of troops or visits to the fleet. It seemed to him that His enormous army was sincerely devoted to him and grateful for taking care of it, and the young fleet was burning with the desire to please its Sovereign leader, who devoted so much labor and time to taking care of it....There is no need to confuse the real Russian Army, valiant and brave, which laid down its lives in the very first years of the war, with the army that betrayed its Sovereign....

“After the army and navy, the Sovereign also loved hunting. Not the usual method of royal hunting, where almost tame animals or specially bred pheasants were driven out to hunters, but difficult hunting, where you need to be able to shoot and have proper composure.

“I remember how on the first skerry voyage on Polar Star, a hunt was organized on one of the islands....All participants returned very dejected, saying that during the whole hunt only once had some bird flown at the Sovereign and he had only got one shot. Soon they sat down to dinner. Suddenly, at dinner, the Sovereign began to recall the hunt and expressed his full pleasure, since for the entire hunt they had only seen one bird and he had managed to kill it, although the shot was very difficult. The organizers of the hunt and its participants shone with joy.

“The sovereign was a sincere believer and a convinced fatalist. Nothing could shake the Sovereign's faith in the Lord God and the conviction that 'not a single hair will fall apart from that willed by the Most High.' In the most difficult moments of the Sovereign's life, when, for example, his beloved son, the Heir Tsesarevich, was seriously ill, or there was unrest among the people, faith in God and Providence did not leave the Sovereign and gave him the strength to endure grief and horror. And during His reign, even in its most brilliant periods, the Sovereign offered fervent prayers to the Lord God and fasted three times a year.

“Because of this, the Sovereign did not believe that it was necessary for the police to protect him with extraordinary measures, and always laughed at the reinforced guards and various precautions.

“I remember how during a visit to a newly built, the Sovereign, having gone ashore and seeing that the workers who took part in the construction were placed in some kind of special rope cordon, immediately ordered the cordon to be removed and the workers to be set free. This measure did not change the order during the entire time of the Highest visit and deeply touched the workers. Almost the same occurrence was repeated during the Poltava celebrations, when the Sovereign unexpectedly, going to the church on the site of a mass grave...saw on the way some barracks that turned out to be built specifically for representatives from the peasants, gathered from all over Russia and located, as it were, in temporary detention. Despite the arguments of the governor, the sovereign went to barracks and spent more than 2 hours among the peasants, talking with them, and asking their needs.

“To complete the description of Sovereign Emperor Nicholas II, it is necessary to mention his exceptional indifference to the conveniences of life and comfort, his modesty in food and wine, and his complete indifference to money. The Sovereign gave all his income to the Russian people either in the form of financial assistance when they asked him for it, or for the upbringing of children, or for the improvement of estates belonging to the Sovereign personally, making the most fertile spaces out of deserts. The Sovereign spent the minimum possible on himself, his family, and on his table, cutting back in everything, stopping balls, ceremonial dinners, etc.

“The August Spouse Empress Alexandra Feodorovna alone approached his tastes, being also a very modest, touching mother, easy to deal with, caring for all loved ones, and with a rare kindness. Her whole life and happiness was her husband and children. And for the sake of her adored spouse, she took an involuntary interest in the affairs of the State to the extent that the Sovereign was pleased to seek advice or support from his only true friend, his spouse. It can be assumed that the Empress was mistaken and involuntarily advised the Sovereign incorrectly, not being aware of all the affairs, especially recently, when the state of her health did not make it possible to always be in the know, but one cannot help but believe that Her Majesty was always guided by a feeling of love for Russia, and in no way to Germany, for which the Empress was boldly accused almost from the Duma podium.

“I remember how Their Majesties returned from Homburg (13), where they specially traveled ss that the Empress could undergo a course of treatment. There were so many stories then about German etiquette, so alien to the Empress, brought up by Queen Victoria, and then accustomed to the Russian Court. Only natural love for her brother also connected the Empress with Germany, but that was all. No wonder Emperor Wilhelm did not like Alexandra Feodorovna, knowing full well that she had become a real Russian and truly Orthodox.

“The Empress had a rather quick-tempered character, but she knew how to restrain herself, and then very quickly retreated and forgot her anger.

“In addition, like the Sovereign, the Empress was very shy, and did not like ceremonial receptions or balls. Instead, she devoted herself entirely to the duties of a wife and mother. The upbringing of her children proceeded exclusively under her personal supervision, which was not at all customary in Russia, even in moderately prosperous homes, where upbringing was entrusted to governesses and tutors.(14)

“The Empress loved her home most of all, which is why it was unpleasant for her to accept strangers in the person of educators into the close and friendly circle of her family.

“The shyness of Her Majesty affected her every move, and especially during solemn or ceremonial receptions. Outwardly, this was expressed by some unusual facial expressions, which gave the impression that the Empress was experiencing something painful at that time. Therefore, many who did not know Her Majesty closely had the impression of her as an unkind woman.

“The Empress was exceptionally kind and indulgent. Once, on the eve of departure on Standart for a skerry voyage, a groom of the chamber to Her Majesty did not like the cabin assigned to him by his position. It should be noted that such cabins were intended for officials during the construction of the yacht and were marked with inscriptions, and calls were made to them from the corresponding Highest cabins. The servants arrived the day before, when there was no one else on the yacht, and the groom was free to inspect all the premises. Thus, he chose one of the retinue cabins for himself and asked the officer in charge of the Imperial quarters on the yacht to allow him to move to the cabin of his choice. Naturally, the officer turned down such a request, explaining that he could not choose his own cabins, since they were all assigned by rank. Then the groom said that he would not go sailing. To this, the officer replied that this did not concern him in any way, and, just in case, reported this to the commander of the yacht, Captain Chagin, who confirmed the refusal.

“The next day, at 11 o'clock, Their Majesties arrived with the family and retinue and, of course, the first thing after the meeting went down to their cabins....After a short time passed, the commander was informed that the Empress was asking him to come to her. Before Captain Chagin could fully enter the cabin, Her Majesty said the following, which is almost verbatim: 'Ivan Ivanovich, I have a big request for you. I hope you will fulfill it.' To this, Captain Chagin replied that Her Majesty's request was an order and, of course, would be immediately executed. 'I know, Ivan Ivanovich, that I am doing wrong, that I have no right to ask you about this, but if you do not want to poison my entire voyage, then fulfill my request.'

“Such an message left Captain Chagin completely bewildered and he asked Her Majesty to tell what the request was. 'Please give my groom the cabin he has chosen for himself, otherwise he will spoil my stay on the yacht.' Captain Chagin replied that, of course, Her Majesty's wish would be fulfilled, but he considered it his duty to report that it is not permitted. 'I know,' Her Majesty replied, 'but I beg you.'

“The kindness of Her Majesty was reflected in everything, but especially in Her relations with people, in Her constant concern for all persons more or less known to Her who fell into a temporary difficult situation, in case of illness, etc. Assistance was extensive, both monetary and and moral. It is hard to imagine what a mass of people Her Majesty helped to get out of financial difficulties, how many children she helped in raising and what a mass of patients she treated in various sanatoriums.

“Many Russians formed the concept of the Empress as a stern woman, with a firm, stubborn character, great willpower but no affection for others, who greatly influenced her August Spouse and guided his decisions at her own discretion. This view is completely wrong. Her Majesty not only treated everyone around her cordially, but rather pampered everyone, constantly worried about others, took care of them, and spoiled her children excessively. She constantly had to turn to her spouse for assistance, since the Heir Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaievich recognized only the authority of his Father and his dyadka Derevenko, He did not obey his mother at all. The young Grand Duchesses also obeyed their Mother but a little.

“In the circle of the Family, the Sovereign always had a decisive vote, and if in state affairs Her Majesty sometimes suggested, for example, decisions, she did so only insofar as the Sovereign himself sought this advice.

“Empress Alexandra Feodorovna was a rarely educated and well-mannered woman. In terms of her knowledge, Her Majesty was a walking encyclopedia, while drawing, playing piano, knowing needlework and being fluent in several languages. After Russian, in which, after several years Her Majesty spoke and wrote freely enough to read our classics, her favorite language was English, and then French. German was never spoken in the Palace, although Her Majesty, of course, was fluent in it. Between themselves, the Sovereign and the Empress usually spoke in English with the sole purpose that His Majesty not forget this language. At first, only Russian was spoken to the children for many years, and then, in tur,n English and French, in order to enable them to practically learn these two languages.

“Her Majesty had a rarely developed sense of duty, and this, as it were, gave her the opportunity to be stubborn in many cases, when, according to her notions, her duty so required.

“Like the Sovereign, the Empress was wholeheartedly Orthodox, having studied the peculiarities of our religion down to all details. Her religiosity sometimes lapsed into mysticism, especially in later years in connection with her serious heart problems and after the unease experienced for her husband and son during the first revolution of 1905-1906. At all church services Her Majesty stood still from beginning to end, without being distracted by anything and praying fervently all the time. When health no longer allowed Her Majesty to stand on her feet for a long time, she sat during the services, but still attended them carefully.

“It should be added to the description of Empress Empress Alexandra Feodorovna that she was in the full sense of the word a beauty, in who was combined everything: regal posture, pleasant facial features, a large stature, a regular figure, a graceful gait, great intelligence, great erudition and education, a talent for the arts, an excellent memory, and kindness of heart. But she lacked the art of charming people, and had no ability or desire to please the crowd. And this, apparently, is necessary for royalty.

“In the circle of close people, when her shyness passed, Her Majesty was the center of mirth and it was impossible to be bored in her presence. Among those people little known to her, Her Majesty seemed to go into her shell and appeared in a completely different light. Subsequently, when the Empress became very ill and often spent whole days lying down, Her Majesty rarely enjoyed herself, and spent most of her time in the intimate circle of her family, where only Vyrubova was admitted.

“The constant illness of the August Son, adored by Her Majesty, played a huge role in her poor health. Every mother suffers over the illness of a child, and here there was the worry not only of a loving mother, but also of the Empress for her Country, whose Throne was to be inherited by her son.

“According to the explanations given to me by the life physician Ostrogorsky (15), who was a permanent doctor of the Heir Tsesarevich, his disease was dangerous only up to a certain age, approximately sixteen or seventeen years.

“It was infinitely hard to see a child charming in every respect, distinguished by great abilities, a great memory, ingenuity beyond his years, and physical beauty, suffering from a chronic disease that occurred from the slightest carelessness when playing. An accidental blow to an arm or leg, or a sudden movement, could cause a rupture of a blood vessel that was difficult to heal.

“I knew the Tsesarevich from the cradle, and had a role in choosing his dyadka Derevenko to help the Heir during his first skerry voyage on Polar Star. During the days of my duty on the Sovereign, Derevenko came to me, having put his pupil to bed, and told me about his life at the Court and about the Heir.

“I saw Aleksey Nikolaevich on a yacht when going around to inspect the team, when playing with the cabin boys, at various performances, and in moments of children's pranks. He always seduced everyone with his clear eyes, decisive look, quick decisions, loud voice, and at the same time softness, tenderness and attentive attitude to everyone and everything.

“The Grand Duchesses at the time described were lovely girls, modestly and simply brought up, treating everyone with affection and courtesy, and often with touching solicitude. They all adored the Heir and spoiled him in every possible way.

“Both the August Parents and the children showed at every step examples of touching love, and one can sincerely say that it would be difficult to find a more perfect family.”

Annotated Notes to Part V

1. Fabritskii was wrong in asserting that Nicholas II's relationship with Orlov was without interruption. As previously noted, the Emperor removed him from the Suite after Orlov made his opposition to Rasputin clear.

2. Konstantin Pobedonostev (1827-1907), adviser to Alexander III and Nicholas II, Ober-Procurator of the Holy Synod 1880-1905. A deeply conservative figure who instructed the future Nicholas II in political principles.

3. Peter Stolypin (1862-1911), Governor-General of Saratov Province 1903-1906, Minister of the Interior 1906; Chairman of the Council of Ministers 1906-1911. Known for widespread reforms and for ruthlessly crushing the remnants of the 1905 Revolution. Assassinated in Kiev by an Okhrana informer.

4. Fabritskii is wrong on this point where Stolypin is concerned. Nicholas II often clashed with his Prime Minister and complained that Stolypin was trying to undermine his position as sovereign.

5. Eugene Alekseev (1843-1917), supposed illegitimate son of Emperor Alexander II, Admiral from 1903; in charge of Russian troops in the Far East during the Russo-Japanese War.

6. Michael Rodzianko (1859-1924), member of the Third and Fourth Dumas, Chairman of the Duma 1912-1917, member of the Octoberist Party.

7. Nicholas Ruzsky (1854-1918), Adjutant-General in the Imperial Suite since 1914, Commander of the 3rd Army of the Southwestern Front (1914), Commander of the Northwestern Front (1914-1915), Commander of the Northern Front 1916-1917. Played an influential role in convincing Nicholas II to abdicate. Shot by the Bolsheviks.

8. Alexander Guchkov (1862-1936), leader of the Octoberist Party, Chairman of the Third Duma 1910; during the War he helped organize the Central Industrial Committees to aid troops. He conspired unsuccessfully against Nicholas II in the months leading up to the abdication, and was present in Pskov on March 2/15 when Nicholas signed his manifesto.

9. Vasili Shulgin (1878-1976), member of the Second, Third, and Fourth Dumas. A conservative monarchist, he was one of the few to argue for the preservation of Romanov rule in the midst of the February Revolution. Together with Guchkov, he traveled to Pskov and witnessed the abdication of Nicholas II.

10. Elsewhere in his memoirs Fabritskii writes that the Emperor usually rose at eight.

11. Fabritskii omits from this schedule Nicholas II's daily walks, his afternoon tea with his family, and the time after dinner usually spent with his children and wife in Alexandra's boudoir.

12. Fabritskii here contradicts his earlier writing on the issue of Nicholas II trusting officials.

13. In 1910 the Imperial family went to Germany so that Alexandra could be examined by a number of specialists over concerns for her heart. They were unanimous in saying that she suffered from no organic heart trouble and agreed that her symptoms she exhibited stemmed from psychological issues.

14. Fabritskii, of course, here ignores the multitude of nannies and tutors who tended to the Imperial children.

15. Sergei Ostrogorsky (1867-1934), Court physician who helped tend to the health of the Imperial c