Semyon Semyonovich Fabritskii: "The Most Precious Memories of My Life..."

Part 4: Continued Annotated excerpts from "Memoirs of the Fligel-Adjutant to Nicholas II."

PART IV

Fabritskii picks up his narrative immediately following his promotion:

“I made all the obligatory visits to the persons of His Majesty's suite, of which I myself became a member. Having visited, among others, Major-General Orlov, I learned from him the reasons that prompted the Sovereign to grant me such a reward. It turned out that a few days after the move of Their Majesties from the yacht Alexandria to the Polar Star, the Sovereign had been speaking one evening with Orlov and asked, 'What difference do you find between the yachts Standart and Polar Star?' Orlov replied that the differences were mainly in the compositions of their crews. The Sovereign was interested in these differences, since both crews were members of the Garde Equipage. Orlov, with characteristic frankness, told him, 'The biggest difference is that the crew of Polar Star is not only disciplined but also educated, whereas that of Standart is not.' The Sovereign fully agreed with this sentiment and explained to Orlov, who had never been on a yacht before, that this must be attributed to a senior officer.

“Returning after our voyage to Tsarskoye Selo, the Emperor at once had informed General Orlov that he had decided to appoint me as an Adjutant. Thus, Orlov knew for a long time that on December 6 I would receive this promotion but he told no one.

“A few days before December 6, the Sovereign summoned the flag-captain Nilov and asked him to suggest the name of a suitable officer from the fleet whom he could appoint as Fligel-Adjutant. To this, Nilov said there was only one suitable candidate, and gave my name. The Sovereign smiled and said, 'I had want to appoint him, but I wanted to check my choice through you.'

“The visits after my promotion to the persons of the retinue went well, but the presentation to the Grand Dukes and Duchesses proved to be very difficult. I had to negotiate in advance with the chiefs of their respective courts or their Adjutants, who reported to Their Highnesses and selected a day and hour for my reception.

“At the same time, my duty began under the Sovereign Emperor. One Fligel-Adjutant was always on duty. The shift lasted twenty-four hours, beginning at half-past ten in the morning. This meant that we would leave Petersburg on the 10 o'clock train for the short journey. At the station, a troika, the traditional vehicle assigned to the adjutant on duty, was waiting. At the Palace, we received reports from the person we were replacing, while new orders came from one of the court officials. The change of Adjutants almost always took place in one of the reception rooms of the Palace.

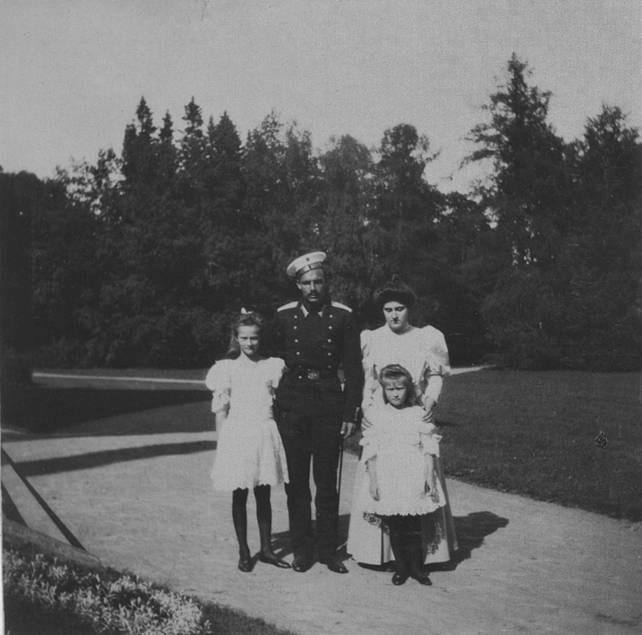

“The Emperor's Day began early. At about 8 o'clock the Sovereign left the bedroom shared with the Empress and swam in his bath, dressed, had breakfast and went for a walk in the garden. From half-past nine to half-past ten, the Sovereign received the Grand Dukes and courtiers, as well as the Marshal, the Palace Commandant, the head of the field office, and the commander of the Composite Regiment. From half-past ten to one o'clock there were reports from the ministers, each of whom had his own specific day and hour to meet the Sovereign. At one of one-thirty luncheon was served in one of rooms on tables specially brought in. Luncheon lasted no more than 45 minutes, after which the Sovereign drank coffee in the Empress's boudoir. After luncheon and until 5 o'clock there were receptions of envoys, foreign guests, trips for various inspections, etc. At 5 o'clock tea was served in an intimate circle, and from 6 o'clock to 8 daily there were additional reports of ministers. Dinner began at 8, after which the Emperor usually stayed until ten with the Empress and their children in her boudoir. After 10 o'clock the Emperor went to his office, where he worked alone, sometimes very late.

“On my very first day I had the good fortune to have luncheon and dinner at the Highest Table in the company of the Sovereign and Empress, since the Children were still small and were not allowed to the common table.

“Entering before the arrival of Their Majesties to luncheon, I saw in the middle of the room a table set with three places and, closer to the door of Her Majesty's boudoir, a small table with several varieties of zakuski.

“The Sovereign entered the room from his side of the palace, greeted me affectionately, and went to the Empress, speaking with her for a few minutes in private before returning and inviting me to partake of zakuski, Her Majesty, after letting me kiss her hand, graciously inquired about the health of my wife and children and expressed her desire to meet them soon. After the zakuski, which lasted some minutes, we moved to the dining table and the servants began to serve soup. Throughout the dinner, the Empress kept up the conversation, addressing the Sovereign in English, and me in French. The sovereign spoke to me in Russian. The Empress graciously explained to me that with the Sovereign she spoke English in order to give him practice in this language, and French with me, since she was still embarrassed to speak Russian, and it would be useful for me to be familiar with French.

“After luncheon, we went to drink coffee in the Empress's boudoir, where she immediately lay down on the chaise. The children came in and surrounded the August Mother and began a general conversation in Russian, since the children spoke exclusively in their native language. It turned out that the Empress spoke Russian quite fluently, making only occasional mistakes.

“After coffee, at about three, I went to receive petitioners who brought requests to the Emperor. A separate room was set aside in the quarters of the Palace Commandant for such receptions.

“The Fligel-Adjutant on duty was obliged to receive and listen to all visitors daily, and then, returning to the duty room, draw up a brief summary of each petition on a special form, attach all numbered petitions, seal them in an envelope and hand them over to the Sovereign's valet by 8 o'clock in the evening. The valet then put this package on the Sovereign's desk.

“Returning from dinner, His Majesty first of all read the petitions and made conditional notes in the margins of the abstract for the Camping Office, where immediately, after reading the petitions, these were received. The field office was supposed to collect all the necessary information overnight and report back the next day.

“Dinner took place in the same order and in the same room. After dinner we again went to the boudoir, where Anna Vyrubova, who had married Lieutenant Vyrubov (1), came with the children. At 10 o'clock Their Majesties released me, and the Sovereign retired to his office. The next day I was relieved by a new adjutant wing and left Tsarskoye without seeing Their Majesties.”

In 1909 Fabritskii was aboard the armored cruiser Oleg when it visited the Mediterranean. Returning to Russia, it called at Portsmouth to meet a squadron from the British Royal Navy, as part of the impending Anglo-Russian agreement:

“From that moment on, the cruiser took its normal place in the detachment, and midshipmen were again transferred to us. It's time to return to Russia. On the way, we were ordered to call at Portsmouth, where the British were preparing an exceptional meeting for us, wishing to set off the emerging Anglo-Russian agreement.

“During the stay of the squadron, a number of ceremonial performances, luncheons and dinners were given, at which the Prince of Wales (2) was present. The admiral, four commanders, and about thirty officers were invited to London, where further festivities were held. Due to the departure of the commander to London, I took temporary command of the cruiser, but on the very first day I received an evening telegram from the commander, ordering me to put the ship in the hands of my assistant and come to London, to meet with Her Majesty Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna, who was then visiting her sister Queen Alexandra.

“Arriving in London, I visited the commander, who told me in detail of the festivities and sadly mentioned how everyone was amazed at the attitude of our Ambassador (3) there, who did not even pay him a visit. Overjoyed by Her Majesty's gracious reception, during which she recalled her voyage on Polar Star, I could not resist and reported to the Empress about the tactlessness of our Ambassador. This story surprised Her Majesty a little, who referred to the Ambassador using a swear word and confirmed that it was difficult to expect politeness from him.”

Returning to Russia, Fabritskii was asked to take over command of Alexandria, while at the same time remaining Fligel-Adjutant to Nicholas II:

“At Peterhof, I was on duty to the Sovereign, who lived at the Lower Palace on the shore, several times that summer. The duties were exactly the same as at Tsarskoye Selo. The only difference was that the quarters for the Fligel-Adjutant on Duty were in the Suite's wing of the Grand Palace, which was about a thirty-minute carriage ride from the Sovereign's residence.

“In the month of July I had to take part in the Poltava celebrations (4) as one of the representatives of the Garde Equipage. This event was highlighted by unforgettable moments of popular enthusiasm from the crowds greeting the adored Monarch.

“The celebrations continued for several days and took place mainly at the site of the battle. On the last day, a ceremonial breakfast was served in the halls of the Cadet Corps. In the inner hall the Imperial table was set for a relatively small group of guests, and in other halls tables were laid with breakfast a la fourchette. Musicians played from the balcony overlooking the entrance hall to the street, where a huge crowd of people had gathered. When at breakfast Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaievich raised a glass to the health of the Sovereign Emperor, the musicians began to play the National Anthem, whose singing was picked up by those in other halls and by the crowd in the street. The master of ceremonies, leaving the entrance hall, turned to a group of officers in the halls with a request to stop singing and go into the street to quiet the crowd.

“Running out into the street with several officers and mingling with the crowd, I saw around me a mass of ladies, in complete ecstasy, with tears in their eyes, singing the anthem, apparently waiting for the Sovereign to come out onto the balcony or to the window. With great difficulty it was possible to make the public understand the appeal to stop. Finally, the singing of the anthem stopped and everyone began to wait for the end of breakfast and the exit of the Sovereign. According to the mood of the crowd, one should have expected an unprecedented touching meeting and a deeply patriotic manifestation. Imagine the disappointment of the crowd when, after a long wait, they learned that the Sovereign Emperor had left from another entrance. It was a pity to look at the sad faces.

“Going immediately to the station, I still had time to see the Sovereign, who told me how touched he was by the behavior of the people and expressions of ardent loyal love. One can only regret that the Sovereign was not given the opportunity to get to know the enthusiasm of the people and let them look at him.”

At the end of September 1909, Fabritskii was informed that he was to accompany the Imperial Family to Livadia in the Crimea.(5) He was to be on duty from October 15 until November 1:

“On the evening of October 14, I arrived at Livadia, where I was immediately assigned a room in the retinue's house. Having made the necessary visits to the retinue and ladies-in-waiting, I found out that the Empress felt very unwell and spent almost all of her time on a chaise. The Sovereign, who was visiting the King of Italy, was expected to return the following day aboard Standart.

“Everyone sincerely lamented the ill-health of Her Majesty, warning me that my duty would be boring and monotonous, since the Sovereign did not leave Her Majesty.

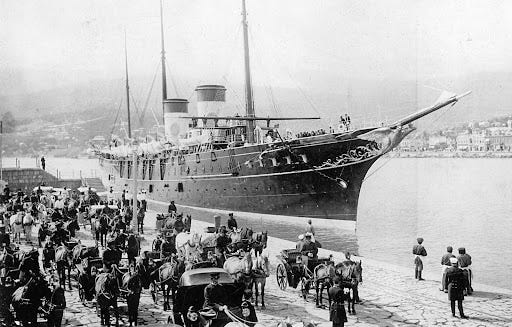

“The next day, observation posts on the shore began to announce the safe approach of Standart. When the yacht passed Ai-Todor (6) the persons of the retinue drove out in cars to the pier to meet the Sovereign.

When the yacht approached the pier, the authorities and retinue were warned about the immediate departure of the Sovereign to Livadia. At this time, unexpectedly, two cars appeared on the Yalta embankment: in the first were the Empress and the August Children, who drove up to the yacht just in time for the installation of the gangway.

“The Sovereign Emperor, being on the bridge, greeted Her Majesty and the children, as well as those who had gathered for the reception. At this time, Her Majesty ordered the doors of the car to be opened, got out of it with the children and, with a rather vigorous step, climbed the gangway to the yacht, where she was met by the Sovereign and the crew of the yacht.

“After 10 minutes, all those waiting on the pier were invited to the yacht for the Supreme Breakfast, during which Her Majesty sat, as always, at the right hand of the Sovereign.

“After breakfast, everyone departed for Livadia, happy to see the Sovereign safely arrived from his trip to Italy and the recovery of Her Majesty.

“Life in Livadia proceeded as follows: the sovereign, getting up, as always, early, at about 9 o'clock in the morning went for a walk in the Livadia garden, returned at 11 o'clock and did business or received officials. At half-past twelve, luncheon began, to which all the persons living in Livadia and constituting the Court and retinue of Their Majesties were invited daily. About 2 o'clock His Majesty, accompanied by invited persons, took a walk or a car ride, returning to the palace by 5 o'clock. After tea in an intimate circle, the Sovereign received reports from the Minister of the Court, the Chamberlain, the Camping Office, etc. At 8 o'clock, Their Majesties usually dined alone. Members of the retinue joined the Court Marshal's table in the dining room.

“I, as a newcomer, had to travel to introduce myself to the Grand Dukes, who lived with their families in the estates personally owned by them not far from Livadia. At that time, Grand Duke George Mikhailovich, Alexander Mikhailovich (7), Nicholas Nikolaievich, and Peter Nikolaievich (8) lived on their estates.

“On the next day of his arrival, the Sovereign ordered me, through his valet, to appear at 2 o’clock at the entrance of the palace, where I would expect his exit. Not knowing the purpose of the call, I appeared in full duty uniform. Seeing me, the Sovereign ordered me to remove my sword, orders and a scarf, and then asked me if I liked to walk. I had to frankly admit that, in the nature of my service, I rarely had to take walks, since my whole life was spent either on a ship or in the barracks. 'Well,' said the Sovereign, 'We will try a short, easy walk for the first time, and we will go along the path to Harax (9) and back along the lower path through Oreanda.(10)

“With these words, the Sovereign set off on his way with a calm, measured step, asking me various questions along the way, mainly concerning the fleet and service in it.

“The walk continued for two-and-a-half hours without a break, with one stop at Harax to smoke a cigarette. By the end of the walk, I could hardly continue, moving only by willpower and enduring excruciating pain from small stones on the roads, which, through the thin soles of my front boots, seemed to penetrate my soles.

“When, having reached the palace, the Sovereign, having thanked for the walk, retired to his chambers, I barely reached my room and immediately changed my shoes.

“The next day, the walk was repeated, but I walked relatively easily, as I was prudently in combat boots with thick soles and, with the permission of His Majesty, had a walking stick.

“Walks continued daily, and their duration increased all the time, sometimes reaching five hours. We walked all the time non-stop, stopping only either to smoke, or to admire the view.

“In Livadia, the Sovereign was surrounded by the following persons: the Minister of the Court; the Grand Marshal; the Palace Commandant; the flag-captain of His Majesty; the head of the Camping Office; the commander of the Combined Regiment, the commander of the convoy (11); the life physician; the Imperial confessor; and the Fligel-Adjutant on duty. Under Her Majesty there was one maid-of-honor on duty and Anna Vyrubova, who at that time had already parted ways with her husband, was visiting.

“In the morning before breakfast, everyone went about their business. After breakfast, if they were not invited for a walk, they expected the return of His Majesty in order to make their next reports. After these report, everyone was completely free and could leave the Livadia area....Very often, in the evenings, the persons of the retinue played cards in the Suite's house or went to see friends or to the theater in Yalta.

“Personally, as a duty officer, I could never leave the palace. On the twelfth day of my stay, during my morning report to His Majesty about those presenting themselves, the Sovereign asked me a question: 'Does nothing urgently call you to St. Petersburg?' To which I replied that I had no personal affairs, but my presence was necessary in the Garde Equipage according to my position. 'I know this,' the Sovereign replied, 'they can wait for you. I ask you to stay at my disposal after duty in Livadia, about which I will personally tell the Minister of the Court.' I could only express my feelings of deepest gratitude. The reception of those who presented themselves began, and I indulged in thoughts of how such a mercy of the Sovereign would be accepted by the retinue and the public in general, with whose envy and hostility I had become familiar from experience immediately after my appointment as Fligel-Adjutant.

“One afternoon at luncheon, the Minister of the Court entered the room and, as always, politely walked around to all those present, greeting everyone and finding something courteous to say to almost everyone.

“A few minutes later the doors of the inner chambers were opened and Their Majesties with the August Children entered the dining room. The Sovereign, having greeted the Minister of the Court, conveyed something to him in words in an undertone, after which the Minister went straight to me and gave me the following order: 'His Majesty orders you to remain at his disposal for an indefinite time after the end of duty.'

“'Yes, Your Excellency,' I replied.

“By November 1, a new Fligel-Adjutant, Colonel Count Sheremetiev (12) arrived as new Duty officer, and I remained as a simple guest.

“Life went on in almost the same order. The sovereign took walks alone, and twice, in order to test the convenience of the new combat uniform and kit for the infantry, he took long walks in full uniform and with a gun. After breakfast, daily walks were made with invited persons. Very often Count Sheremetyev, who had been close to the Sovereign since childhood, was invited to walk, as was member of His Majesty's Suite, Major General Komarov (13), who commanded the Combined Regiment, and myself.

“At the same time, Her Majesty with the August Children took excursions in carriages or in cars. In the evening after dinner, sometimes Their Majesties invited a small group of people into their circle, during which the Sovereign usually sat down to play dominoes with three partners, and Her Majesty occupied the rest of the guests with conversation, enchanting everyone with her tenderness, intelligence, knowledge and beauty. Around 11 o'clock, Their Majesties released their guests, and themselves retired.

“Tennis was played several times in the morning from 10 o'clock to 12 o'clock. Unfortunately, there were no officers among the retinue or officers who could match the Sovereign in terms of strength. Her Majesty did not take part in the game, but sat near the players, surrounded by the children and those invited.

“As a rule, if a day's walk was taken without guests, I knew from experience that His Majesty would carry on a conversation about something concerning the naval department. And indeed, having taken a few steps, the Sovereign asked me a question, to which he demanded the most detailed explanation. Questions were raised about serving in the fleet; supplying ships with materiel; preparing cadets of the Naval Corps for officer positions; about the position of Adjutants and members of the Grand Ducal Suites in the fleet; about training recruits; and many other subjects.

“My detailed report on the supply of ships continued for more than two hours without interruption, and the Sovereign, having listened to it to the end with full attention and asking several questions, said: 'You have been reporting to me this interesting question in every respect for more than two hours. The Minister of the Navy has one hour a week to report. It usually begins with a report to me of the highest orders, on awarding pensions, on dismissal due to seniority, then some current affairs. Next, I have to coax answers from the Minister to my questions. As for the supply of ships, although I am an autocratic Sovereign, I assure you that after I made a demand to reconsider this provision, the Minister asked for permission to form a special commission, the work of which will drag on indefinitely.'

“From such repeated conversations about various matters, I realized with what distrust the Sovereign treated almost all ministers, and how isolated the Sovereign felt himself.

“Once I received a letter from my colleagues in the Guards crew, in which, among other things, they asked me to find out directly from the Sovereign whether the rumor that had spread around Petersburg was true about the elimination of the rank of lieutenant commander....During one of my walks, I asked the Sovereign about this, to which I received the following answer: 'I don’t think so, since I don’t know anything about this.' But soon, another courier, who arrived with reports for the Sovereign's signature, brought a prepared order to eliminate the rank of lieutenant commander and introduce a new rank of senior lieutenant.

“During one of the walks, a conversation turned on the difficulty of managing large units or formations, and the Sovereign, remembering his unexpected accession to the Throne, said, 'When my Father died, I was just the commander of the Hussar Life Squadron and spent the first year of my reign only looking closely at the management of the country. At that time, the Secretary of State for Finland, General von D. (14), who had held this position even under my late father, took advantage of my confidence in himself and, having given the report to me for approval, then filed into it a lot of things that we had not discussed. Several days passed. One day the valet reported to me that the Minister of War, General Vannovsky, asked permission to come immediately with a report on an urgent matter. I gave permission. After half-an-hour, an excited Vannovsky entered my office, bowed and said, “Why did Your Majesty deign to offend me, Your faithful servant?”

“'I don’t understand, explain what’s the matter,' I said. To this, General Vannovsky handed me a printed sheet from the Senate printing house with the new regulations on Finland approved by me, which was supposed to be promulgated the next day. Having examined it, I was personally convinced of a forgery, since on the first page was what I approved; everything else in it had not been discussed with the Secretary of State. After that, I had to tell General von D. about the impossibility of his service to me.'

“After concluding my duties at Livadia, I was struck by the several things. On the one hand, I was approached with all sorts of requests, and on the other hand, everyone who had any opportunity tried to hurt me. In the latter pursuit, unfortunately, even the Grand Dukes took part, one must think at the instigation of the persons of their retinue.

“One day after a walk, the Emperor ordered me to come at a quarter to eight to the entrance to Standart, where dinner was to be held in the wardroom. The very fact that I was not aware of such a thing was quite significant, since I myself was not only an officer of the Guards crew, which included the yacht, but I was the Emperor’s Fligel-Adjutant and assistant commander of the crew for combat unit.

“Dinner was served in the wardroom. This did not have the character of a formal dinner party, and was only slightly better than our usual ones. After dinner, they played lotto, and the Empress gave the winner some kind of trinket as a keepsake.

“Several days passed. One evening, Palace Commandant Adjutant General Dedyulin (15) played cards with General Komarov; Rear-Admiral Chagin, the commander of Standart; and myself. At the end of the game, General Dedyulin expressed regret that it would not be possible to continue the game the next evening in view of the upcoming Imperial Dinner on the yacht. To this, I said that, on the contrary, as I had not been invited to the yacht, I would be completely free. Then General Dedyulin turned to Chagin and, perplexed, asked if this was true and how it was that I was not invited. Chagin replied, 'Invitations are made by the Sovereign.'

“The next day, having not received an invitation from the Sovereign at the end of the walk, I obviously took advantage of the free evening and left for Yalta to visit friends.

“The next morning I received an invitation to tennis. Approaching the site, I found two officers of Standart also invited to the game. Seeing me, they came up to say hello and, excited, said that yesterday they were looking for me all over the city, since the Sovereign and Empress, having arrived on the yacht and received an invitation from the commander go to the wardroom, had asked if I had arrived. Having received a negative answer, they said that they would wait for my arrival. Messengers were immediately sent to search for me, and only when they returned without result did Their Majesties go to dinner.

“At the end of the game, tea was served, during which the Sovereign, looking at me with a smile, asked me how I liked yesterday's cinematic performance on Standart. 'Yesterday I was not on the yacht, Your Majesty,' I replied. 'Oh yes, I forgot. Why weren't you there?' asked the Sovereign. I replied that I was not invited. This ended the conversation.

“From that time on, the Sovereign himself invited me to dinners on the yacht.

“At the same time, Colonel Komarov of the Combined Regiment came to me and asked if I played bridge and if I could be free for one evening to participate in a competition organized by Grand Duke George Mikhailovich, since one of the proposed participants suddenly fell ill. Confident that Their Majesties would always willingly let me go to the Grand Duke, I answered in the affirmative. Satisfied with the success, Colonel Komarov, who was instructed by the Grand Duke to urgently find a substitute for the sick man, left immediately for Harax, where he reported to the Grand Duke that a suitable player he had found in my person. The Grand Duke was satisfied and thanked Colonel Komarov, but at that time the voice of Grand Duchess Marie Georgievna was heard: 'No, we cannot invite Fligel-Adjutant Fabritskii, because this may displease Their Majesties, whose guest he is. Despite the assurances of Colonel Komarov that there could be no misunderstanding, the invitation was withdrawn.

“Long before November 6, a day specially celebrated by Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaievich, the entire retinue of the Sovereign knew that an invitation to a ceremonial dinner had been extended to everyone at Livadia. And indeed, on November 6, Their Majesties and the whole retinue, except for me, spent almost the whole day at the estate of Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaievich. Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich also had a big hunt, to which Their Majesties were invited with all their retinue, except for me.

“The day of December 6 was approaching, the Name Day of the Sovereign and the holiday of the Guards crew. In St. Petersburg, usually on this day, a large parade was scheduled for those units of the troops that celebrated the holiday of the unit that day.

“This year, the Sovereign ordered a parade at Livadia for all troop units in the Crimea, and requested the name of an officer to take command. For this purpose, a small meeting was held under the chairmanship of the Minister of the Court, at which, after planning the parade, they began to select the commander. Flag Captain Nilov offered to appoint me, as I had much experience and was completely free from service at the time; I was also an officer of the unit celebrating its holiday that day. To this, the Minister of the Court, from whose attention little was hidden, said, 'Let's leave him alone. Although he is quite suitable for this appointment, it will only arouse jealous talk.' The parade was commanded by General Dumbadze.(16)

“I remember this not from a feeling of malice, which I neither then nor now had towards anyone.

“'We need only bring someone closer to us for evil rumors to start about them,' the Sovereign once said to me in the presence of the Empress, who silently agreed with this. And they were very right, since human envy and malice have no boundaries, and in this they did not spare even Their Majesties, who, meanwhile, set an example of exceptional marital happiness and an almost holy life.

“My stay in Livadia dragged on until December 9, when, finally, the Sovereign allowed me to go to St. Petersburg.”

Annotated Notes for Part IV

1. Alexander Vyrubov (1880-1919), Senior Lieutenant and official in the Ministry of the Imperial Navy; married Anna Taneyev in 1907 at Tsarskoye Selo. They were divorced within two years after Anna claimed that her husband was mentally unstable and impotent.

2. George, Prince of Wales (1865-1936), second son of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra; succeeded to the British Throne as George V and reigned 1910-1936. A first cousin to both Nicholas and Alexandra.

3. Alexander von Benckendorff, Russian Ambassador to the Court of St. James's.

4. The Bicentennial of the Battle of Poltava took place in the summer of 1909.

5. Livadia was the Imperial estate in the Crimea, comprising several palaces a few miles distant from Yalta.

6. Ai-Todor was the Crimean estate of Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich.

7. Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich (1866-1933), fourth son of Grand Duke Michael Nikolaievich; in 1894 he married Alexander III's eldest daughter Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna. Established the first naval aviation training school in 1909. After a time imprisoned in the Crimea following the revolution, he left the country in 1918 and spent the rest of his life in exile.

8. Grand Duke Peter Nikolaievich (1864–1931), brother of Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaievich; married Princess Militsa of Montenegro in 1889. Imprisoned in the Crimea after the Revolution, he left Russia in 1919 with his family.

9. Harax was the Crimean estate of Grand Duke George Mikhailovich and his wife Grand Duchess Marie Georgievna.

10. Oreanda was originally developed as a Crimean estate by Nicholas I and his wife Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. It was later used by the Konstantinovichi branch of the family, but Nicholas II purchased a significant park of the estate for his own use.

11. A reference to the Cossack Konvoi Regiment, which did guard duty for the Imperial Family.

12. Count Dmitri Sheremetiev (1869-1943), Fligel-Adjutant to Nicholas II.

13. Vladimir Komarov (1861-1918), Major-General in the Imperial Suite.

14. Nicholas II was referring to Woldemar von Dehn, who served as Secretary of State for Finland from 1891-1898.

15. Vladimir Dedyulin (1858–1913), Major-General from 1900, Adjutant-General in the Imperial Suite from 1909, Palace Commandant from 1906-1913.

17. Ivan Dumbadze (1851-1916), Major-General in the Imperial Suite from 1912, Mayor of Yalta 1914-1916.