Part II

Continuation of excerpts from My Service in the Old Guard, 1905-1917, published in Buenos Aires by Dorrego in 1951.

Makarov wrote of two linked incidents involving Major-General Alexander Alexandrovich Zurov, who Commanded the Semyonovsky Life Guards Regiment. Here, I have combined them to form a complete narrative, although they appear more than fifty pages apart in Makarov’s memoirs:

“One day Second Lieutenant Nicholas Ilyin unfolded a telegram and began to read it silently. The telegram was two and a half lines:

“‘Congratulations to the Life Guards Semenovsky Regiment on the regimental holiday. I am sure that the descendants of the Petrovsky Amusement Regiments will always and everywhere prove worthy of their glorious ancestors. Nicholas.’

“When I read this telegram I couldn't believe my eyes. No, it can't be! The good sovereign could not send such a cold, dry and official telegram to his Semyonovsky Regiment! The only explanation is that he accidentally waved it without reading. On those occasions when he personally congratulated us, he spoke in completely different tones. Tomorrow, when the telegram was to be read to the regiment, everyone would be bitterly resentful. And all the people in Russia who respect and are proud of the Semyonovsky Regiment would be insulted to the depths of their souls.

“Ilyin himself at that moment was too happy to allow anyone in the whole world to be upset or offended. The situation had to be saved. Whether it was an omission, an oversight, or a malicious intrigue, it was quite unthinkable to read the telegram as it was written. Ilyin thought for a moment. In the back of his mind, an important decision was brewing. He dictated a new telegram: ‘I cordially congratulate my dear Life Guards Semyonovsky Regiment on the happy day of their regimental holiday. I am deeply convinced that the valiant descendants of the Petrovsky Amusement Regiments will always and everywhere prove themselves worthy of their glorious ancestors. Nicholas.’

“This way it turned out quite decently. It was impossible to be offended by the telegram in this form…. It must be said that the system of tsarist telegrams was complex and delicate. Telegrams of various kinds were sent: Condolences to widows; on the occasion of the death of all important persons; but mainly congratulatory ones, and to dignitaries, and institutions, and societies, and regiments. In addition to several guards regiments, the sovereign was the chief of many other military units. Two officials of the Tsar's Campaign Chancellery were in charge of this matter, and the chief of them was the Preobrazhensky officer Adjutant Drenteln. Wherever the Tsar went, to the Crimea, to the Finnish skerries, to Moscow or to Kiev, he accompanied him everywhere, because during his entire 23-year reign, the Tsar was never ‘on vacation,’ like all of us sinners, and he carried out his official duties continuously.

“Drenteln knew his business masterfully. There was never a case when those who were entitled to it were offended by not receiving a token of Imperial attention. The main difficulty was not even remembering all the dates and numbers. For this purpose, special calendars were kept, which were reviewed every day. The most difficult thing was to compose a telegram in which each word had to be weighed on the apothecary's scales, and at the same time in such a way that the telegrams would not resemble each other as much as possible. And since, with all the richness of the Russian language, there is still a limited number of congratulatory words in it, we got endless combinations and permutations of invariably single-value components. If one institution received a message saying: ‘I respect your useful work for the benefit of the Motherland,’ then another institution received, ‘I appreciate your fruitful work for the benefit of the Fatherland,’ and not a single word more or less.

“Historically, it is known that Tsar Nicholas II treated the performance of his Imperial duties in the most conscientious manner and carefully read everything that was presented to him. He also read all the telegrams that were sent on his behalf, but he never changed anything in them. He knew that it was impossible to write better and more politically….

“Things seemed fine, but on the fifth day word of the telegram change reached the Commander-in-Chief of the Guards and the St. Petersburg Military District, Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaievich, who was formidable in his anger.

“Nicholas Nikolaievich flew into a rage, summoned the unsuspecting Regimental Commander and shouted at him in a formal manner: ‘A baby, a boy, a second lieutenant without a moustache, and without duty, without any hesitation, alters to his liking the Emperor's own words, words that have the force of law throughout the entire length of the Russian Empire, between the five seas! What are the rules, what discipline in the regiment, where such things are possible?’

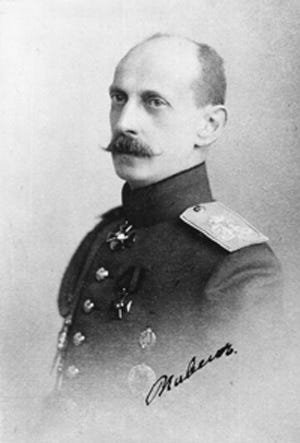

“Major-General Alexander Alexandrovich Zurov, a former native of the Transfiguration, a graduate of the Military Academy, an exemplary officer, a fine man and one of our best commanders, stood at attention like a schoolboy, pale as a sheet, and biting his lips. I stood there and couldn't say anything. Outwardly, the offense was truly monstrous.

“Zurov returned to his Commander's House, sat down at the table and wrote a letter of resignation. At the age of 44, his military career was over….

“At his farewell regimental dinner, the House of Romanov was represented by three members, Konstantin Konstantinovich, Kirill Vladimirovich, and Boris Vladimirovich. The first two were connected with Zurov in the Preobrazhensky Regiment, the third in ours. After a toast to the outgoing regimental commander, the deafening cheers lasted five minutes. The duration was unprecedented. At last Zurov, touched, got up and, restraining his excitement with all his might, began to thank us, to say how much he loved and respected our regiment, and how hard it was for him that ‘unexpected circumstances’ had forced him to part with it. The moment was highly charged. When Zurov sat down and there was silence for a moment, Boris Vladimirovich, expressing the general mood, in a low voice, but in such a way that everyone could hear, pronounced the expressive two-syllable Russian word ‘bastard.’ It was clear to whom this word referred. If only he had appeared in the hall at that moment, Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaievich would have received a very unfriendly greeting. At that time everyone was indignant.”

Makarov recalled a training exercise enacted for Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaievich, and a visit to Krasnoye Selo by Nicholas II:

“The Hight Command was waiting for the results of the shooting with such impatience that they immediately reported them to Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaievich. The latter immediately telephoned…and said that he was going to the regiment himself at once to congratulate the ranks and officers, after which he would stay for dinner. Indeed, about 20 minutes later, three horsemen appeared on the highway. The first one was of enormous stature on a huge gray horse. Behind him was an adjutant and a messenger. The visit is of the most unofficial kind. The regiment was lined up on the front line, all unarmed. Nicholas Nikolaievich greeted them and shouted, ‘Come to me!’ Everyone, both soldiers and officers, rushed to him and surrounded him in a tight ring. He spoke loudly and praised everyone. He could scold, and often for nothing, but when he praised, he praised generously and spared no words. Both the officers and the officers were delighted, and the hurrah was crazy. Nicholas Nikolaievich prudently did not get off his horse. But the regiment became so excited that an attempt was made to carry him with a horse, as a sort of equestrian statue. Finally, the ranks reluctantly dispersed to their tents, and Nicholas Nikolaievich, surrounded by officers, rode to the Assembly. By this time, the corps commander Danilov, the division commander Olokhov and the brigade commander Zayonchkovsky had also arrived. Due to the brevity of the warning, in the sense of food, they did not have time to cook anything special for the distinguished guest. We gave him an ordinary four-course weekday lunch. But already after the soup, the wine began to flow like a river. We sat down at two o'clock in the afternoon and got up at six. Only Novitsky was completely sober. Commander Danilov, taking the heroes of the day Lode and Sveshnikov by the collars, declared his love for them for a long time…. By the end of the dinner, Nicholas Nikolaievich wished to see the officials again. Everything was muddled: most of the supporting staff was gone, and the usual camp costumes were not according to order…. Nicholas Nikolaievich came out on the terrace and again thanked and praised the men. When he finally climbed into a carriage and drove away, a screaming crowd rushed after him and escorted him almost halfway along the Krasnoselsky highway.

“In the next camp…we again earned ourselves a shooting triumph in exercises. At the competition of the entire guards, the regiment scored the imperial prize. This prize was a big silver plate with Ural stones, quite beautiful. When it was handed over, an incident very characteristic of our old order occurred….The Tsar did not come solely to the regiment to hand over the prize, and it was assumed he would give it to us during a review on the field, where he was to undertake a review. At the appointed hour, our regiment joined the others on the parade ground…. In due time, a line of cars appeared on the road from Krasnoye Selo. The Tsar came out. The commander shouted, “Regiments, attention!” The music thundered out God Save the Tsar. The Tsar, wearing out regimental uniform, greeted us and reviewed the ranks. Then he walked to the commander, thanked him for his service, and congratulated him in advance of handing over the prize…. Suddenly, there was confusion in the Imperial retinue. What had happened? It turned out that the ceremony would have to be postponed: it was for a trifling reason. There was no prize to hand over: they had forgot to bring it! An adjutant rushed back to fetch it, and in the meantime the Tsar was asked to inspect the machine gun battalion, to which he meekly agreed. Forty minutes later, the prize finally arrived, and the ceremony went off as planned.”

Makarov left an interesting description of the frustrations and expenses he experienced when new uniforms were introduced:

“The question of clothing was the worst. In the old tsarist army, uniforms were expensive and complicated, especially in the guards.

“When I joined the regiment in 1905, we had a lamb's hat with a St. Andrei's star and a long uniform with a slanting side, of a coachman's cut. This form was introduced during the reign of Alexander III, who did not like any unnecessary decorations and bright forms. This coachman's uniform with wide trousers and knee-high accordion boots, was – given his huge stature, red beard and bulky figure – the only military uniform that did not look like a disgrace on him. In his eyes, this uniform had another advantage: it was the closest to the Russian national dress.

“In 1908 the Minister of War, Sukhomlinov, a vain and frivolous man, persuaded the Emperor Nicholas II, who was extremely easy to persuade of everything that did not concern the limitation of the autocracy, to introduce into the army the old uniforms of the time of Alexander II. It was possible, for example, to increase the number of heavy artillery or machine guns, but it was decided to postpone this. The whole army was hastily re-clothed, and it is terrible to think how much public money had been wasted on this masquerade.

“In the soldiers, at least the lower part of the body remained untouched. The officers had to change their entire dress uniform from head to toe. Instead of lamb caps, they wore ones of white, whose only excuse was that they were historical…. The body was dressed in a tight, short double-breasted uniform, with two rows of buttons. On ceremonial occasions, a red lapel was attached to this uniform. Everyone had to throw away their old uniforms, because it was impossible to change them into new ones. I had to throw away my trousers as well. In the old form, they were worn very wide. Under the new one, they were almost skintight. I had to throw away my boots as well. Shagreen or patent leather boots, with hard tops, which were worn in the cavalry, were not in honor among us. When, in the 1890s, Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich commanded the Preobrazhensky Regiment, he started the fashion for long, soft patent leather boots, which made many folds on the foot, like an irregular accordion. When you put on these boots you had to use a wooden pull as you couldn't hold them any other way, the boot being more than a meter long. These boots were worn with rather high heels. When the new uniform was introduced, these boots also had to be thrown away, as they did not fit the new uniform. With the new uniform, we began to wear ordinary semi-soft patent leather boots, with two or three pleats.

“After the introduction of the new uniform, the combinations of officers' clothing turned out to be as follows. Depending on the occasion, an officer could put on a ceremonial uniform, which meant: a cap with a white sultan; a uniform with a red lapel; epaulettes; a breastplate (at first this existed only in the Petrovsky Brigade, but it seems that in 1910 it was introduced in all infantry regiments); orders that one might have; a silver belt; the so-called ‘scarf;’ trousers; high boots; white suede gloves; and, of course, a sword that had always to be worn. Then there was the usual guard uniform. This meant a cap, no longer with a sultan but rather with a pompom; a uniform without a lapel; epaulettes; trousers; and high boots. There was no breastplate, but a revolver was worn, on a belt and with a silver cord around the neck. There was also the ordinary form of dress. It was worn when appearing before the authorities, mainly for reviews, in church, at pannikhidas, at the removal of the shroud, etc. It consisted of the same uniform without a lapel; a cap with a pompom; with a breastplate; trousers; and high boots. There was also a ‘ballroom uniform.’ This was the same uniform without a lapel; a cap with a pompom; long pants; and small patent leather shoes. This uniform, quite elegant, could also be worn at ceremonial dinners.

“Together with caps and lapels, in 1917 the Russian officer's frock coat passed into history…. In the time of Nicholas I and earlier, the collars on frock coats were worn very high, but with straight sharp angles. Fastened with all hooks, such a collar covered the neck and supported the cheeks. On the other hand, the frock coat was allowed to be unbuttoned, which was done by the officers of that time. In order for the high collar not to cut the neck too much, the neck was wrapped with a black silk kerchief, and a white waistcoat was worn under the frock coat. In modern times, the corners of the collar were rounded, which made the frock coat more comfortable to wear, but the cute silk kerchief disappeared and was replaced by a simple silk scarf, which was worn on the collar with an elastic band around the neck. In practice, as our collars were very high, and the starched collar was not visible underneath, this scarf was often replaced by a simple silk patch, which was sewn directly to the collar from the inside. The unbuttoned frock coats have also officially disappeared. Unofficially, in intimate company, in memory of the past, we still unbuttoned our frock coats, and underneath, as in the old days, we wore high pike waistcoats with gold buttons. As the sides were lined with red cloth, the unbuttoned frock coat with a white waistcoat and a black little tie was a beautiful, elegant uniform. With a uniform and a frock coat, white shirts were supposed to be worn. To wear a colored shirt under a uniform or frock coat was a crime.”

Twice every month, as Makarov remembered, at least one Grand Duke would attend the usual Thursday regimental dinners:

“These large dinners started at 7 p.m., and there were many invitees. Everyone had the right to invite a guest, military or otherwise. The table was decorated with flowers from our own little greenhouse, a grand appetizer was served, and music blared from a choir. Several of our former officers of the Semyonovsky always came. Almost always this included Grand Duke Boris Vladimirovich, who was a member of our regiment but did not serve in it. Sometimes his brother Kirill Vladimirovich came, as a member of the Preobrazhensky Guard. These brothers were distinguished by the fact that, though they drank like horses, they always behaved quite correctly.

“With the permission of the regiment commander, Kirill Vladimirovich once brought his wife Victoria Feodorovna and the English writer Eleanor Glyn, who was then staying with them, to one of the Thursday dinners. This was completely against the rules, since the ladies were allowed in the Assembly only in the offices located on the second floor, and by no means in the large common room. This time, an exception was made. In English literature, Eleanor Glyn’s reputation was not high…but her novels, especially those of foreign life, were read in England and sold well. Dinner was very discreet, and we drank little. Officers who spoke English were seated next to the writer. She was very interested in the life of Russian guards officers. At that time, a new romance was already brewing in her soul. We tried in every possible way to convince her that the life of the St. Petersburg officers was very similar to the life of their London brethren. They, like the British, go to the barracks and teach their soldiers, have breakfast and dinner at their messes, play sports, and go to the theater and to their friends. The writer nodded her head and agreed with everything.”

Makarov recalled maneuvers at Krasnoye Selo:

“As crazy as it may seem, one of the major expenses of officers in the camps was maneuvers. The so-called ‘small maneuvers’ were held, usually in the very last days of July, and lasted four or five days, so that by the time of the Transfiguration Feast on August 6, by the time of the Krasnoselsky races…and by the time of the ceremonial performance at the Krasnoselsky Theatre, everything would be over. Our regiment went on maneuvers having, in addition to the required provisions wagons, at least 30 hired peasant carts. On them were the officers’ own tents and the Assembly tent, a huge canvas structure for 100 people, and then the kitchen wares, with cooks, table linen, silverware, dishes, crystal, tables, folding armchairs and chairs, and most importantly a whole cellar of wine. The most important items were the boxes of champagne. When we stopped for the night, the first thing we did was to set up the assembly tent and set the tables. Dinner was served, as always, with four courses, on plates with the regimental monogram changed after each course, as well as knives and forks, and in front of each was a beautifully folded snow-white napkin. There were five glasses of different shapes and sizes, and between them, a touching detail, one green glass for Rhine wine. And all this took place in maneuvers, where the officers were supposed to sleep on the ground and eat from the soldiers' field kitchens. How Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaievich who, whatever you may say about him, was a military man, allowed this is incomprehensible. I can also say that there was nothing like this in the regular army. There the maneuvers were maneuvers, not picnics.

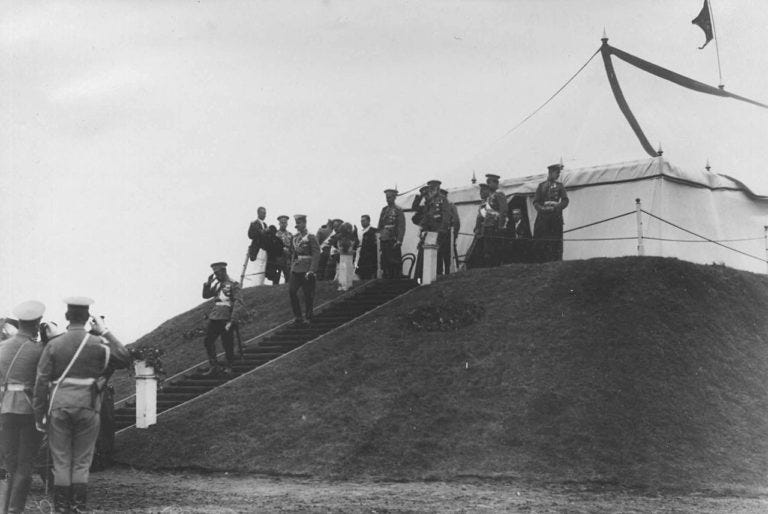

“It should be noted that, in general, the Guards’ ‘small maneuvers’ in the period before and immediately after the Japanese War were a complete joke. For the first three or four days, the troops were engaged in movements, sometimes making quite tiring marches. All this was a preparation for the last day of the general attack, which began from both sides, at a certain hour, and was always led to a definite and well-known point where the Tsar’s tent stood on a hill. At the last minute, in the very center of the battle, with binoculars in his hands, Tsar Nicholas II could admire how dense chains of tall guards were coming at him from two opposite sides, preparing for the final knockdown. About 100 paces before the mound, the officers, waving their sabers, with a shout of ‘hurrah,’ dragged their troops into the mix, and the men, closing in with the commander, selflessly rushed forward. However, it was also not recommended to get too carried away and run toward the Imperial carriages or mound with bayonets fixed.

“At the most decisive moment, when the clash was about to occur, the Tsar gave a signal. Two of the convoy's life trumpeters, standing next to him, raised their silver horns and played. The troops stopped dead in their tracks, and the maneuver, to everyone’s joy, was over. Twenty minutes were spent in the ‘debriefing of the maneuver,’ to which the senior commanders were summoned, and then, never later than 2 o'clock in the afternoon, at lunchtime, all the big officers, including the commanders of the regiments, went to the Tsar's tent for a snack. For other men, tablecloths were spread out on the grass near the tent, on which were placed plates of bread, ham and cold meat, and bottles of beer and wine. The ranks ate from their field kitchens. On those days, the Tsar treated more than 2,100 officers to a cold luncheon.”

In June 1906, the Semyonovsky Life Guards Regiment was invited to Peterhof to attend a garden reception given by the Emperor and Empress. Makarov recalled:

“The reception was to take place at the Tsar's dacha in Alexandria, in a marvelous park with huge old trees and green lawns of amazing beauty. The day before, we arrived from Krasnoye Selo by train and spent the night in the Lancer barracks. And the next day, at four o'clock, the whole regiment marched in formation to Alexandria, with a chorus of music at its head. As far as I remember, it was not very far. In front of the gates of the park we stopped, cleaned ourselves again and brushed the dust off our boots. All were in white, officers in white tunics, soldiers in white shirts, and all without weapons: no swords, no rifles, no bayonets.

“The weather was such as only can be in St. Petersburg on clear, sunny, mild windy days. Having arrived at the appointed place, we stopped and stretched out in two ranks, company by company, the officers in their places. The Tsar came out. He, too, wore a white tunic and was without arms. Our regimental uniform was present only in the blue band of his white summer cap. He walked around the rows and said hello. Then came the command ‘Disperse!’ and we separated. The ranks went to the edges, where there were prepared tables with treats, tea, sweet rolls, sandwiches and sweets. The Tsar and the commander of the regiment also went there to make the rounds of the tables.

“And we, the officers, went in the other direction, where under the trees there was a huge round tea table, covered to the ground with a snow-white tablecloth, and on it a silver samovar, cups, biscuits and all sorts of food. The Empress, in a white lace dress, sat at the table and received the guests. The Tsar's daughters – the eldest was 10 years old – were running around. The two-year-old heir, who could not walk because of illness, sat in the arms of his diadka, the sailor Derevenko. Then he was handed over to our senior sergeant-major, R. L. Chtetsov.

“There were almost no courtiers. The aide-de-camp on duty for that day was Grand Duke Boris Vadimirovich, who did not actually serve with us, but was on the lists of the regiment. He often wore our uniform and was considered to be our officer. We were all in a joyful and cheerful mood. The Tsar was also cheerful and, as always, very easy to deal with. He was afraid of clever ministers, he was shy in front of senior generals, but here, in the familiar environment of soldiers and officers, he felt like the colonel, the commander of a battalion of the Preobrazhensky regiment, as he had once been, and remained so for the rest of his life.

“The Tsar’s girls were having a great deal of fun. With loud shouts they rushed across the meadow and played tag with the young officers. The Empress performed the duties of the hostess. She poured tea and personally passed a cup to everyone. As far as could be judged from the short phrases about children, about the weather, or about tea, sweet, strong, with lemon or milk, she spoke Russian quite fluently, though with a strong English accent. But she performed her tasks with such obvious suffering that it was pitiful to look at her. At that time, she was already the mother of five children and had held the title of All-Russian Empress for eleven [sic] years.

“She seemed to feel embarrassed and awkward in the company of some unknown 40 officers, who were also rather embarrassed in her presence. And yet I was struck by the fact that when she asked her simple questions, her face turned red. This was clearly noticeable, since in those days decent women did not yet paint their cheeks. And when she held out the cup, her hand trembled violently. But, of course, it wasn't just shyness. Already in those days, our first lady, the wife of the Tsar, was a sick and deeply unhappy woman.”

Makarov returned to the subject of Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich when discussing World War I:

“The First Guards Corps (there were already two of them at this time of the war) was then commanded by Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich…. At about 7 p.m., I went to the dining tent for dinner. About 20 officers gathered. They introduced me to the Grand Duke.

“I had seen Paul Alexandrovich only in the street before this, and here for the first time I examined him attentively.

“The youngest son of Alexander II, like the entire older generation of the Romanovs, was very tall and, at almost 60 years old, was unusually handsome, with a special noble beauty….Paul Alexandrovich said a few words to me when introduced, but I do not remember now what they were….A. F. Stein, who was in his position as Commandant of the Headquarters, talked to him every day and for a long time, told me that among the great authorities he had seldom seen such a simple, modest, approachable, and cordial person as Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich.

“At the Chief Officer's chair…sat an amazingly handsome and glorious 19-year-old boy in the cornet epaulettes of the Life Hussar Regiment…. He was the youngest, favorite son of Paul Alexandrovich, from his second marriage, Prince Vladimir Paley.

“No sooner had we begun to eat cutlets with tomato sauce, the same menu as at the Army Headquarters, than the trumpeter in front of the celestial observer began to sound the alarm.

“Stein rose from his seat and said loudly: ‘Your Imperial Highness, gentlemen officers, please come to the shelter.’

“The second German raid in one day! Since I first arrived with my regiment in 1914, the war had become more turbulent!

“Thanks to the efforts of the economic Stein, this matter was apparently much better organized at the corps headquarters than at the army headquarters. Not only were deep, strong shelters dug for all the men, with rolls of logs, but even the corps horses were brought into the deep ditches on an air raid. The officers' shelter was quite solid and spacious. There would be enough space for another 20 people. There were a lot of benches and even a table in the middle. Of course, our shelter would not have saved us from a direct hit, but we were completely safe from shrapnel.

“No sooner had we entered than the explosions began. Everyone sat in silence, occasionally exchanging words. Paul Alexandrovich sat at the table and smoked a cigarette in a thin enamel holder. Only Paley did not sit still. Like all lively boys, it was absolutely necessary for him to run pit and learn what was happening. He opened the door and ran up the stairs.

“‘Vladimir, please don't go out!’ Paul Alexandrovich's tired voice said.

“‘Now, Papa, I'm fine, I'll just see where it hit!’ And he started to run out again.

“‘Cossack,’ Paul Alexandrovich ordered, ‘close the door and don't let the cornet out!’

“‘Yes, Your Imperial Highness.’

“An elderly Life Cossack, smiling affectionately into his beard, blocked the door with his broad back.”

Finally, Makarov remembered Nicholas II, and his last meeting with him:

“A weak-willed and colorless man, Emperor Nicholas II could never enjoy popularity among officers. He did not know how to ignite or inspire people and reigned for 21 years, living, so to speak, ‘on capital.’

“I can't forget the last time I introduced myself to him. In the very first days of June, 1911, all of us officers who had graduated that year from higher military schools, with the exception of the Military Academy, which was presented separately, had to arrive at 11 o'clock in the morning at the Tsarskoye Selo railway station by special train. At the Tsarskoye Selo station, court carriages were waiting for us…and in about 10 minutes we were already rolling up to one of the entrances of the large Catherine Palace. There were about 120 of us officers. All of us were dressed in summer uniforms, some with medals, and all wearing brand new academic badges on the right side of the tunic. In the great Catherine Hall, the Engineering Academy lined up in one line, on the right flank the Artillery Academy, behind it the Law Academy, then the Quartermaster's Academy, and finally, on the left, the Artillery, behind it the Juridical Academy, and finally, on the far left, five men of our class from the Eastern Languages Division.

“The officers were very diverse, in the most varied uniforms, in ranks from captain to lieutenant. But they all had one thing in common. Everyone's eyes shone with restrained joy and calm satisfaction after a well-executed and difficult task. Each of them, at the cost of three years of hard work, after many worries and sorrows, finally broke out of the many thousands of gray officers, made their way into the world, and secured for himself a tolerable existence for the future…. For each of these 375 officers, this clear, fresh June day was momentous, and one could guarantee that none of them would forget it until their deaths. It was also possible to guarantee that if the Tsar spoke to them only a few words that day, even only those that were necessary, they would never forget them, either.

“At last, footsteps were heard in the distance along the enfilade, and the Emperor appeared in the doorway, accompanied by the Minister of the Court, old Count Freedericksz, the palace commandant, General Voeikov, and the aide-de-camp on duty.

“A colonel of the permanent staff of the Engineering Academy, who was our teacher and stood on the right flank, said loudly: ‘Gentlemen, officers!’ The Tsar began his rounds.

“‘What brigade are you?’

“‘The 3rd Grenadier Artillery Brigade, Your Imperial Majesty!’

“‘Are you stationed in Moscow?’

“‘Yes, Your Imperial Majesty.’

“A nod of the head, a full bow of the officer, and to the next one, ‘What battalion are you?’

“‘The 16th Engineer Battalion, Your Imperial Majesty.’

“And so on and so forth, to all 120 people. With those who had been in the Japanese War and had military orders (there were several of them), the conversation was more meaningful. With everyone else, it was a long, tedious, and useless task. It lasted an hour and a half. On reaching me – I was the last to stand, and there was only one guardsman in the whole party – the Tsar, seeing the familiar uniform, stopped and asked about the regiment and the officers he knew. Visibly relieved, he talked to me about these easy topics for about two minutes.

“Then he came to the middle, rubbed his cuff with the upper part of his hand, smoothed his moustache, and said a few words in his distinct voice. If he had been able to play a little on people's souls, this is what he should have said to these officers:

“‘Gentlemen, your efforts have been crowned with complete success. A wide road is open to you. In our army, over time, you will occupy the biggest and most responsible positions. On this important and happy day, I say to you: do not pursue a career and never, under any circumstances, make a deal with your conscience. Temptations await you but let your sense of duty always be the measure of what you can and cannot do. I am sure that you will devote all your strength to serving the Motherland. I wish you success on this difficult but glorious path!’

“And if he had said that, what a deafening ‘hurrah’ all those officers would have shouted at him.

“Unfortunately, nothing even like this was said. The following was said:

“‘I wish you to make good use of your knowledge,’ and turning to us Oriental language specialists, ‘and to you with your languages.’ That was it.

“After this speech, the Emperor, as it was written in the official reports, ‘retired to the inner apartments,’ and we were taken to the next room, where a cold luncheon à la buffet was prepared, in other words, one that is eaten standing up.

“At the end of December 1914, Emperor Nicholas II, near Warsaw at Garvolin, made a review of the Semyonovsky Regiment. There was a thaw. Shifting on the muddy ground, we waited for two hours. Finally, when it began to get dark, the Tsar's cars arrived. A small colonel stepped out of the first car. Sixteen musicians (the rest were killed while serving as orderlies in battles) played the hymn God Save the Tsar on their crumpled and flattened pipes….With his usual gesture, the Emperor smoothed his moustache and greeted us. We answered him and shouted ‘hurrah.’ After, this short man, with a gray and sad face, walking along the front, was looked at by some with curiosity, but the majority with indifference. And the ‘hurrah’ sounded indifferent. At that time, we did not feel any enthusiasm at the sight of the leader. And warriors need inspiration, and the longer they fight, the more they need it.

Before the First German War, the overwhelming majority of regular officers were monarchists. No one taught us to be a monarchist, and no one from the authorities ever told us about the advantages of the monarchical system over the republican one…. We were monarchists by tradition and by inertia. From the age of ten, on the ‘Imperial days,’ of which there were 10 a year, we went to solemn prayer services, ate a delicious dinner, and in the evening, we went to the theaters. The Tsar was an indispensable part of Russian life. Both we and our grandfathers and great-grandfathers were all born under the tsars. We are accustomed to remembering Russian history by reign. Almost continuously, the tsars ruled Russia from the time of Ivan III, i.e., for more than 500 years. And then one day, quite unexpectedly, it was wild and strange to learn that the Tsar had fallen out of Russian life. No one grieved, but for the first few days people walked as if they were lost. Being without a monarch was not so much uncomfortable as unusual. However, the great event, apart from its moral effect, had no effect on the officers.”