Over the forty-plus years of my Romanov career (such an odd thing to say and something that would have surprised thirteen-year-old me to no end) I have had some incredible experiences. From sitting in palace rooms ordinarily closed to the public; examining émigré photo albums and archives; becoming friends with writers whose books helped guide my interest and sustain my journey; and fending off packages, letters, and telephone calls from would-be claimants and their families, it has amounted to a lifetime of extraordinary access that I think has largely been due to luck as I gradually researched and wrote one book after another.

Some of those experiences have involved members of the Romanov Family. As I was once again sorting through some boxes the other day, I came across hundreds of letters and was reminded of one very peculiar, very comical incident that took place some thirty years ago. Even now it still strikes me as one of the most bizarre experiences I have ever had – something like a Bigfoot encounter in terms of how stunned and amazed I was. No matter how strange the below may seem, I swear it’s true.

The story starts in April 1995. I had flown from Seattle to San Francisco for a few weeks to do some research and visit some houses in the area that I had always wanted to see. I stayed at the Hotel Majestic, a fantastic place full of Victorian charm and which is the city’s oldest continuously operating hotel, having miraculously survived the 1906 earthquake. I had a corner room on the fifth floor, with a great sitting area in a turret.

My biography of Empress Alexandra had been published by Citadel Press the previous summer, and I was then working with Allan Wilson, my editor there, on the final manuscript for my biography of Prince Felix Yusupov. That meant that I got regular faxes from my publisher which continued through my trip; I confess at the time I thought it was immensely posh to have the concierge fawn over the fact that I was an author whose publisher kept sending things to me at the hotel. In one Allan warned that he was overnighting to me a rather long letter he had received from a Russian princess. He also called the hotel to alert them that I would be receiving a package from a princess. If anything, that bit of information seemed to increase my profile with the concierge!

The next day the package duly arrived. It was some forty-odd pages, written in a variety of colored inks on sheets torn from a yellow legal pad. The author was Pamela, wife of Prince Michel Cantacuzène, Count Speransky. For the sake of the story, let me give some background.

Prince Michael (though he preferred the French Michel) Sergeievich Cantacuzène, Count Speransky, was born in 1913 on his family’s estate near Gomel in Ukraine. The Cantacuzènes were, of course, one of the most prominent aristocratic families in the Russian Empire, and the Prince’s grandmother was attached to the court of Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna. In 1899, his uncle, also Prince Michael, had married Julia Grant, granddaughter of American President Ulysses S. Grant, a lady who rose to prominence at the Court of Nicholas II and authored several books. After the Revolution, young Michel and his family fled to Europe and he eventually settled in South Africa. In 1950 he married Barbara Hanbury-Williams, granddaughter of Major-General Sir John Hanbury-Williams, who had served as British military representative at Russian Army Headquarters during World War I; ironically, Barbara’s mother Zinaida was also born a Princess Cantacuzène, making bride and groom distant cousins. The couple had two children, Prince Sergei and Princess Alexandra, but divorced in 1963.

Shortly after the divorce, Michel married again. His second wife was Pamela Jeppe, born in Johannesburg in 1927 and a member of a prominent South African family. They had no children. The couple lived in South Africa and then France before finally moving to America. Michel died in his home at Westerly, Rhode Island, on December 31, 1999; Pamela returned to South Africa and died there in June 2014.

The Princess’s initial letter to me was a bizarre, rambling, critical dissection of my biography of Empress Alexandra, with passages written sideways in the margins, Post-it notes tacked on to sentences to add additional thoughts, and comprised of a variety of colored inks, which made it somewhat difficult to follow. This, as I learned, was simply how she wrote, in an oddly stream-of-consciousness manner that bizarrely echoed the letters of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. Most of the letter addressed mistakes she thought I had made (some true, others a matter of opinion), though I do recall how she rather startlingly asked, “Are you a Jew?” She warned me against using respected historian Richard Pipes as a source because, she insisted, he was a Jew: it wouldn’t be the first time that such blatant antisemitism reared its ugly head. But she also asked many questions and so, once I returned home a correspondence began, which continued over the next three years. Luckily, I saved all of her letters which today make for some astonishing reading. At various points she suggested that I rewrite actual quotations from memoirs (passages from books by Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich come to mind), insisting that she was somehow able to divine what they really should have said! This encapsulates the relationship. Pam, as I was quickly asked to call her, was a crashing snob; she relished her married title of Princess and even had it printed on her personal checks. I once accompanied her to a grocery store to buy lobster for dinner. She paid by check; the clerk asked for identification and Pam simply pointed to “Princess M. Cantacuzène” on the check, as if that resolved the issue!

I suppose it is natural for husband and wife to adopt mutual interest, but Pam went overboard: she was more royal and more Russian than Misha, as I was asked to call the Prince. I remember staying with them the weekend of the funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales in September 1997 – I had gone back east to attend the auction of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor’s possessions, which were being sold by Mohammed Al-Fayed and which was cancelled when his son Dodi died with Diana. The dining room of the Cantacuzènes’ small colonial-style house was filled with hundreds of books on Imperial Russia, which Pam relentlessly consulted in her efforts to “correct” my knowledge over the years. There were a few items of genuine interest, too: in the living room Pam and Misha kept a small seal made by Fabergé using a piece of shrapnel collected from the Neva Embankment after a live shell was fired at the Winter Palace from artillery at the Fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul during the Epiphany Ceremony in January 1905.

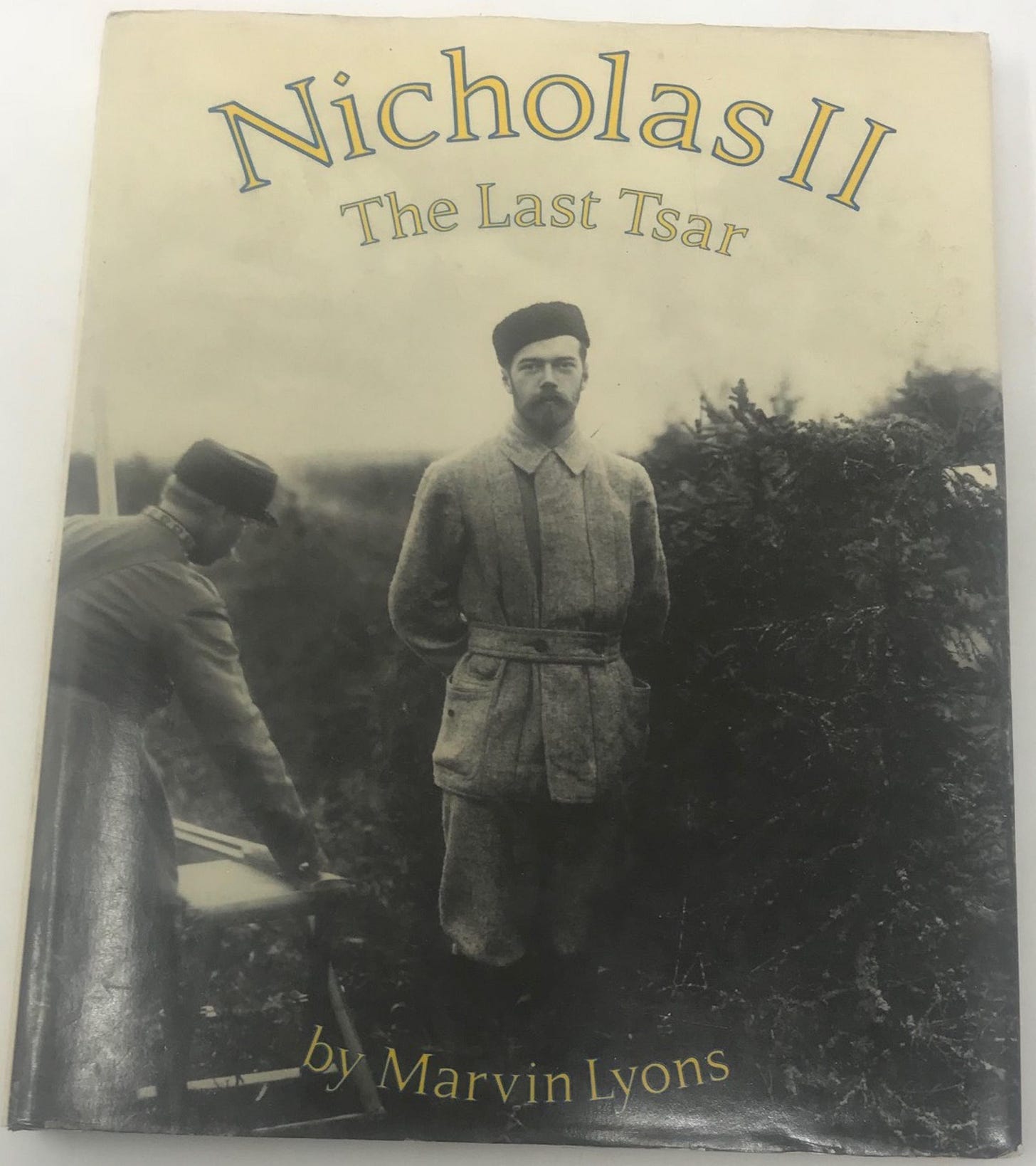

But back to the autumn of 1995. After a few months of letters and telephone calls, Pam had asked me to help Misha write his memoirs, and so I was heavily involved in that project. Then one day she rang me, asking if I could drive up to Canada. She was in touch with author and historian Marvin Lyons, and he wanted to meet me. I knew of Marv: he had written 1974’s Nicholas II: The Last Tsar, a coffee table book full of rare photographs of the Emperor and his family and which was one of the first Romanov books I owned. He had also authored Russia in Original Photographs, 1860-1920, and edited the memoirs of Prince Serge Belosselsky-Belozersky and of Vladimir Bezobrazov, Commander of the Imperial Guards during World War I. At the time, Marv lived in Richmond, British Columbia, which was a mere 90-minute drive away, and so I eagerly agreed to meet him.

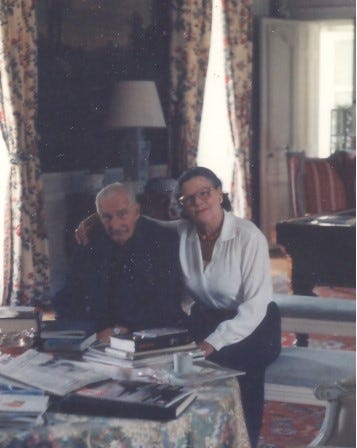

With directions in hand, I set off one morning and after crossing the border wound my way through the Vancouver, British Columbia suburbs to Richmond and to a rather non-descript ranch house on Bates Road. Marv greeted me at the door and ushered me in to a living room crowded with books, papers, and the most astonishing Imperial relics, including half a Benson & Hedges cigarette in a case that he explained Nicholas II had partially smoked and which a courtier had retrieved from an ashtray.

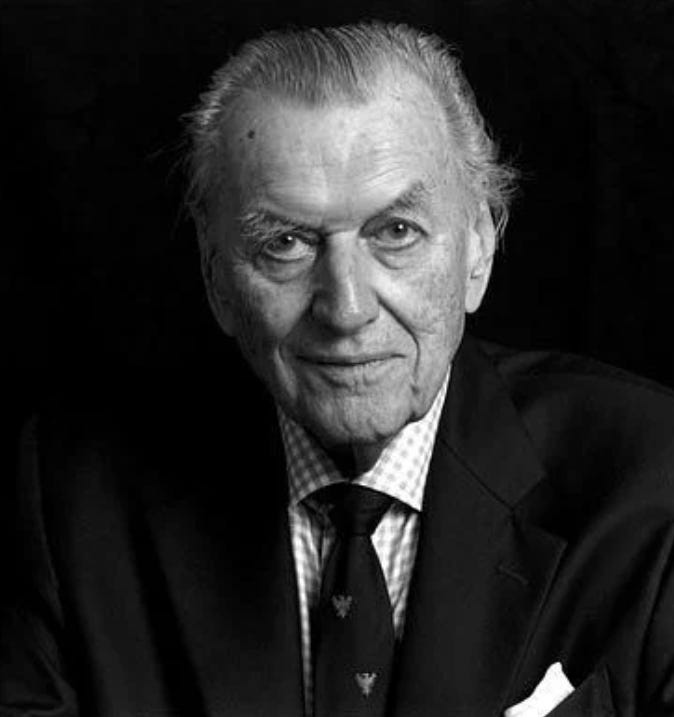

At the time Marv had amassed what he called the Corps de Pages archive, an extensive collection of unpublished memoirs by former cadets of the institution. After an hour or so of examining his archives and chatting about books, he came to the point: Would I be willing to speak to Prince Nicholas Romanov? The Prince, he explained, wished to talk to me. Of course I agreed, and Marv grabbed the telephone and dialed the number in Switzerland. He spoke with the Prince for a few minutes and then put me on the phone.

At the time I didn’t give this much thought, but it had obviously all been worked out beforehand. I had previously been in touch with the Prince, asking if he might write an introduction to my biography of Empress Alexandra; he offered a brief paragraph for me to use in one of the letters we exchanged. He now said that he had read the book with great interest and thought it was well done.

I still had no idea what was going on: why Marv wanted to meet me, or why he wanted me to speak to the Prince. Those mysteries were soon revealed. I had previously mentioned to Pam that I was friendly with Brien Horan, who had acted as American legal counsel to the late Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich and who continued on in a similar role with his daughter and successor Grand Duchess Maria Vladimirovna. That’s why I found myself in a British Columbia living room speaking over the phone to a Russian prince in Switzerland: Nicholas wanted me to use my connection with Brien to ferret out information about Maria Vladimirovna’s plans. More specifically, he wanted to know about her position regarding the Ekaterinburg remains and if she would attend any funeral in Russia.

The full import of this settled over me. A little over fifteen years earlier, I’d had my first exposure to the story of the last Romanovs courtesy of television, watching the old series In Search Of… episode on Anna Anderson, followed by the 1956 Ingrid Bergman film Anastasia and then 1971’s Nicholas and Alexandra all within the space of 30-odd hours. And here I was, sitting in the living room of a man whose book had proved pivotal to me courtesy of the wife of a Russian Prince, speaking to a Romanov descendant who wanted me to act as an intermediary with another Romanov descendant concerning plans for Nicholas and Alexandra’s funeral. I would never have imagined any of these developments.

I told Prince Nicholas that I would ask Brien Horan about this. But the Prince wanted me to do this secretly, without mentioning that I had spoken to him or was acting on his request. I suppose I understood some of this: after all, the Romanov Family – specifically the Vladimirovichi and Nikolaievichi branches in exile – had been in a perpetual state of war since 1969, when Grand Duke Vladimir declared that after his death his daughter Maria would become head of the Imperial House and act as “curiatrix” of the non-existent Russian throne. The two sides didn’t talk to each other. I told the Prince that I would ask but added that I wasn’t going to lie to Brien if he wanted to know why I was raising the subject.

I do remember reaching out to Brien and asking about the issue. At the time, it seemed as if new a date for the funeral was being set every six months or so – I had already twice booked flights to St. Petersburg as another author friend of mine had suggested that I could likely attend the service. So it wasn’t entirely unusual for me to inquire about any new developments. I learned that Maria Vladimirovna was waiting for a decision by the Russian Orthodox Church and was unlikely to act independent of their acceptance of the Ekaterinburg remains as those of Nicholas II and his family.

All of this could easily have been put in a letter but once again I found myself summoned up to Marv’s house in Canada to speak with Prince Nicholas and flesh out what I had heard. I did so and, as I seem to recall, it was at this point that the Prince asked me to pose a second round of questions related to some very specific issues. He wanted to know when Maria Vladimirovna would next visit Russia, and where she was going. I also remember that he asked if I could learn the names of those people in the Russian Orthodox Church and the government with whom she was in contact. I told him I would try but added that this request was so specific that I could hardly pretend the questions came from me.

It’s a bit fuzzy now. I’m pretty sure I wrote or spoke to Brien and told him that Nicholas was trying to use me as a conduit so that he could learn what the Grand Duchess was up to. What I cannot recall is what I ended up conveying to Prince Nicholas. I am pretty sure, though, that I told him I had alerted Brien to the fact that Nicholas was asking the questions.

I know there was a third conversation with the Prince, again conducted in Marv’s living room a few weeks later, but after that I gather they decided that I’d provided all of the useful information I could. I never saw Marv again (he died in 2014), but I continued to work with Misha Cantacuzène on his memoirs for the next few years, and after a hiatus of a decade I resumed a friendly correspondence with Prince Nicholas Romanov, which continued until his death.

I have a lot of stories to tell about the Cantacuzènes and Marv, but those will have to wait for another day.

I look back on all of this with some amusement as well as disbelief. When I first became fascinated with the last Romanovs I would never have imagined that one day, however briefly, I’d be acting as an unofficial go-between for members of the extended family. The very idea would have blown my thirteen-year-old mind.

Hi Greg, great article! I knew Marvin back in the day. We had a long and very frequent email exchange. He was paranoid at the time (not sure if that was always the case) that Putin was out to get him. At one point in our communications he reneged on an agreement which I thought shabby. He was a real character and I remember the day I told him something he wasn’t aware of, with proof. He was furious to be corrected, still makes me smile. Would love to hear your stories one day.