Homosexuality in Nicholas II’s St. Petersburg: A Look at 1908’s Scandalous Expose K sudu!

Translated and annotated by Greg King

In 1908, a small book called K sudu! (To Court!) was published in St. Petersburg. The provocative title evoked memories of Emile Zola’s J’Accuse about the Dreyfus Affair in France, but the subject was completely different. While Zola had attacked the government for its overtly antisemitic and fabricated case against Alfred Dreyfus, K sudu! offered up a scandalous expose of the homosexual underworld of Nicholas II’s St. Petersburg.

The book was the work of poet and journalist Vladimir Ruadze. Little is known about him – even the exact year of his birth remains a mystery. He apparently came from a family of wealthy government officials. After the 1905 Revolution he published a number of biographical works about famous Russian trials, but for the most part these seem to have won little attention among the reading public. After completing several volumes of poems, Ruadze sank back into obscurity, resurfacing briefly after the Revolution when he edited a weekly newspaper in Vyborg.

Shortly after this, Ruadze emigrated to Europe, and eventually settled in Dubrovnik. Here he continued publishing poetry and historical works while working as a journalist for various newspapers. He died in 1968 and was buried in Dubrovnik.

K sudu! apparently first appeared sometime in the early autumn of 1908, released by St. Petersburg publisher Kommerch, Typolitan, Vilenchik. Although it had been approved for publication by the Imperial government, it was deemed so controversial that authorities soon swept in and confiscated all available copies. The issue went to court as the following year the government ordered that all known copies be destroyed. The copies which were sent, by law, to the Russian State Library in St. Petersburg and Moscow, were not destroyed, but were instead locked away after censors removed at least four of the most incendiary pages, which comprised an entire chapter.

The work apparently owed its genesis to the Eulenburg scandal in Germany which first erupted in 1907. Journalist Maximilian Harden had accused members of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s intimate circle, including Philipp, Prince of Eulenburg and General Count Kuno von Moltke, of being part of a nefarious homosexual clique. The ensuing controversy resulted in numerous suicides and multiple trials for libel, forming a sort of German equivalent to the legal furor surrounding Oscar Wilde a decade earlier.

K sudu! consists of a mere 117 pages and is divided into 35 chapters; sometimes these amount to little more than a page or two. Ostensibly the book was an expose of what the author presented as the “corrupting” and “immoral” homosexual underworld of the Imperial capital. But as historian Dan Healey notes in reality the book was more akin to “a peep show of private vice intended to titillate and amuse.” Ruadze’s criticisms cut across the entire social spectrum, from the aristocracy to the lowest of prostitutes.1

Not only did the book wallow in that which it purported to abhor but, ironically, it also – as Healey writes – served as a “quasi-fictional Baedecker” to the Imperial capital’s “homosexual subculture.” Ruadze thoughtfully provided a list of St. Petersburg’s “secret” homosexual meeting places, in effect directing readers to a series of locations including bathhouses and gardens where they would encounter either men of similar tastes or male prostitutes who eagerly plied their trade for a pittance.2

To help set this translation of K sudu! in context, it is useful to know something of the historical background. Somewhat surprisingly, and in contrast to present day conventions, the Russian Orthodox Church differed radically from the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Western churches in its moral denunciations, at least up until the onset of Romanov rule.3 Although it officially defined homosexual acts as mortal sins, there had always been a flourishing subculture within Russia. One Nineteenth Century historian recorded: “Nowhere, either in the Orient or in the West, was this vile, unnatural sin taken as lightly as in Russia.”4

Peter the Great enacted the first laws against homosexual acts in 1706, which defined them as “unnatural lechery.” This was not a specific law against homosexual acts, per se, but rather a prohibition on any sexual activities that ran counter to the Church’s official teachings and included anal sex between a man and a woman, and even sexual relations where the woman took the top position. Punishment for those found guilty of such offenses was death by being burnt at the stake. Ten years later, Peter altered the Military Code. Recognizing that homosexuality was prevalent within the Imperial Army, he dictated that such offenses be punished by flogging rather than death. Even so, this applied only to members of the military.5

It was Nicholas I who finally eliminated the death penalty for members of the military found guilty of homosexual acts in 1832. Three years later, a new law was enacted which extended severe penalties of homosexuality to Russia’s civilian male population.6 In 1845, this was codified under Article No. 995 of the Criminal Code, which defined the offense of muzhelozhstvo, or anal intercourse – whether between men, or between a man and a woman – as a “vice contrary to nature.” Those found guilty were subject to exile in Siberia for up to five years; a conviction involving a minor resulted in exile and a sentence of hard labor.7

Although officially, at least, homosexuality was condemned, it was often tolerated and even indulged in by those in the highest positions of Peter the Great’s Table of Ranks. As the Nineteenth Century progressed, it was understood that homosexuality was often practiced in many of the country’s most prestigious educational institutions, including the famous Corp des Pages.8 Homosexuality was so prevalent among the highest echelons of the military that it was derisively referred to as “the Guards’ Disease.” Certain units, like the elite Preobrazhensky Life Guards Regiment, were notorious for the way in which officers quite openly engaged in same-sex relationships.

In 1903, a new criminal code was introduced that further reduced the penalty of imprisonment for three months. Prosecutions, however, were rare. This changed in the wake of the 1905 Revolution. Although Nicholas II’s October Manifesto had made concessions and granted certain freedoms, the government suddenly took a new interest in prosecuting homosexuals. Perhaps this reaction owed something to the Eulenburg scandal and a heightened awareness that Russia, too, had an active homosexual subculture. What is certain is that, in the years before World War I erupted, prosecutions for homosexual activity by the Russian state nearly tripled from the previous decade.9

There was an irony in this. Whispers about the sexual tastes of certain members of the Imperial Family were widespread; other Romanovs, like Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, managed to successfully conceal their secret lives even in the face of blackmail. Prince Vladimir Meshcherskii served as editor of the influential and ultraconservative newspaper Grazhdanin and was a favorite and close advisor to both Alexander III and Nicholas II. He was also among the capital’s most notorious homosexuals, a fact well-known by members of the Imperial Family. In 1887 Alexander III actually covered up an incident when the Prince was caught having sex with a young soldier at Gatchina.10

And, while officially condemning homosexuality, it had always flourished within the Russian Orthodox Church. In the reign of Nicholas II numerous clergy were quite open about their sexual preferences. This tolerance became the subject of popular scorn when Rasputin’s proteges, including Pitirim, who as Metropolitan of Petrograd was the highest-ranking member of the clergy in Russia, were appointed to prominent positions.

The flowering of new art and literature in Nicholas II’s reign, dubbed the Silver Age, also saw the rise and public prominence of a handful of writers who brought the subject of homosexuality out into the open. There was, as Dan Healey notes, “a comparatively rich and vigorous range of voices speaking about same-sex love. Works of literature and criticism, satires and counterblasts, and translations of foreign tracts and apologetics brought the question within the reading public’s reach, disseminating new concepts and languages to describe mutual male and mutual female eros.”11

The capital’s Bohemians – Sergei Diaghilev, Zinadia Gippius, Anna Akhmatova, Marina Tsvetaeva – all freely and openly indulged in same-sex relationships. Two years after the easing of censorship under the October Manifesto, a pair of startling novels appeared in St. Petersburg bookstores. Each offered a chronicle of contemporary homosexual life. In Tridtsat' tri merzosti (Thirty-Three Abominations), Lydia Zinovyeva-Annibal penned Russia’s first novel of lesbian love. This was an overwrought tale of an affair between the unnamed narrator and her actress lover, full of melodramatic scenes culminating in a tragic suicide – a stereotypical unhappy ending, perhaps included to appease those who might object to the book’s content, although authorities confiscated it when it was first published.12

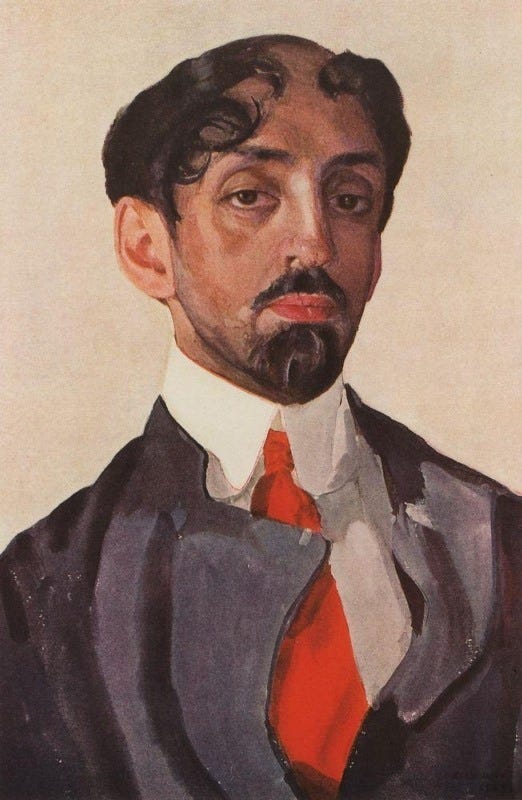

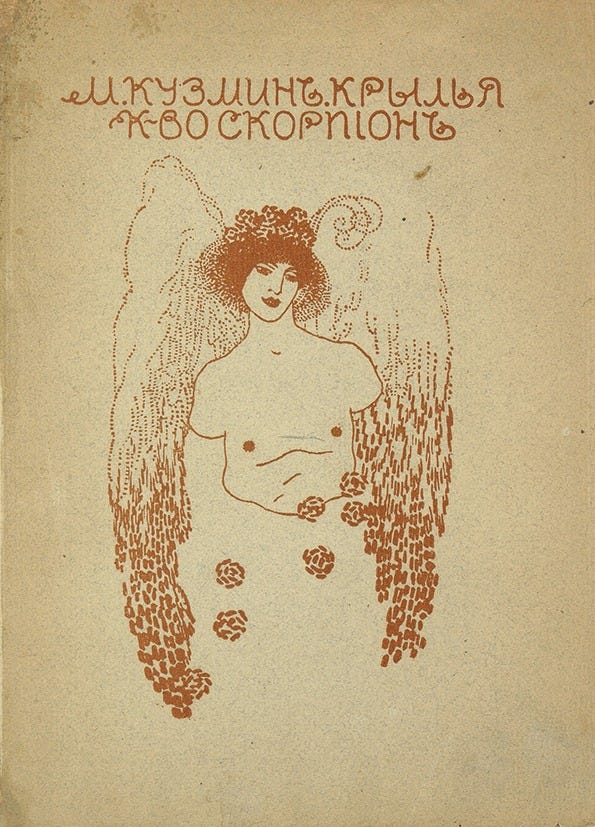

Far more influential was Michael Kuzmin’s Krylia (Wings). In contrast to Tridtsat' tri merzosti, here there was no tragic ending – the novel was an undisguised celebration of same-sex love and holds a special place in history, Healey notes, as “the first modern coming-out story with a happy ending in any language.” The narrative centers around a young, middle-class St. Petersburg student named Vanya, whose journey of discovery eventually leads him to embrace his homosexuality.13

All of this led to much debate of the issue in the country’s newspapers and journals. For the first time the issue of homosexuality was a common topic in the arena of public discussion. In 1911 philosopher Vasili Rozanov produced a screed against homosexuality entitled Lyudi lunnogo sveta (People of the Lunar Light), in which he denounced “sodomites” as “perverted” and “depraved.”14

Vladimir Nabokov, father of the future author and one of the most prominent lawyers in St. Petersburg, took a much different approach. He published a plea that the State should do away completely with laws against homosexual activity. The Russian Government, he boldly declared, had no business interfering in the private sexual relationships of its consenting citizens. This was a striking position, particularly within the profoundly Orthodox Russian Empire, and Nabokov found himself ridiculed and subjected to threats.15

Having set the historical stage, I think it is also helpful if readers have some understanding of homosexual life in St. Petersburg. This is also important to understanding the book, as many of the places Ruadze mentions existed and had, at the time of his publication, acquired reputations as gathering spots or meeting places for the capital’s homosexual community.

Those seeking same-sex encounters in Imperial St. Petersburg, as in most societies, developed certain code words, signals, and even manners of dress to identify each other. “Our circle” indicated sexual kinship; “aunt” or “auntie,” similar to the use of the word “queen” in English, was used to denote men with same-sex preferences. Bright red neckties and handkerchiefs were apparently taken as a recognizable symbol of homosexuality. A few of the more daring and flamboyant members of this milieu even took to sporting rouge and lipstick.16

Certain locations in St. Petersburg were known as spots where men seeking same-sex encounters could reliably find either willing partners or male prostitutes. The stretch of the Nevsky Prospekt from Znamenskaya Square to the Anichkov Bridge was known as a homosexual meeting place. The Passage, a covered shopping arcade which had opened on the Nevsky in 1848, was a favorite cruising area, as was the Mikhailovsky Square with which it was linked. Teenaged boys seeking easy money could be solicited along the Fontanka Canal; in the Tauride Palace Gardens; and especially around the Cinizelli Circus, where they would ask for cigarettes or a light amid a “nonchalantly thrown glance.”17

Off-duty members of the Horse and Cavalry Life Guards Regiments looking to make extra money loitered ear the public toilets at the Zoological Gardens. “A soldier passing along glances significantly [at a potential client] and goes off in the direction of the water closet,” recorded one contemporary, “checking to see if [the man] is following him. If he does, then he pretends to see to his bodily functions and tries to show off his member.” For 25 kopeks, a soldiers would allow his genitals to be fondled; if a client wanted sex, the charge was usually 3-5 rubles.18

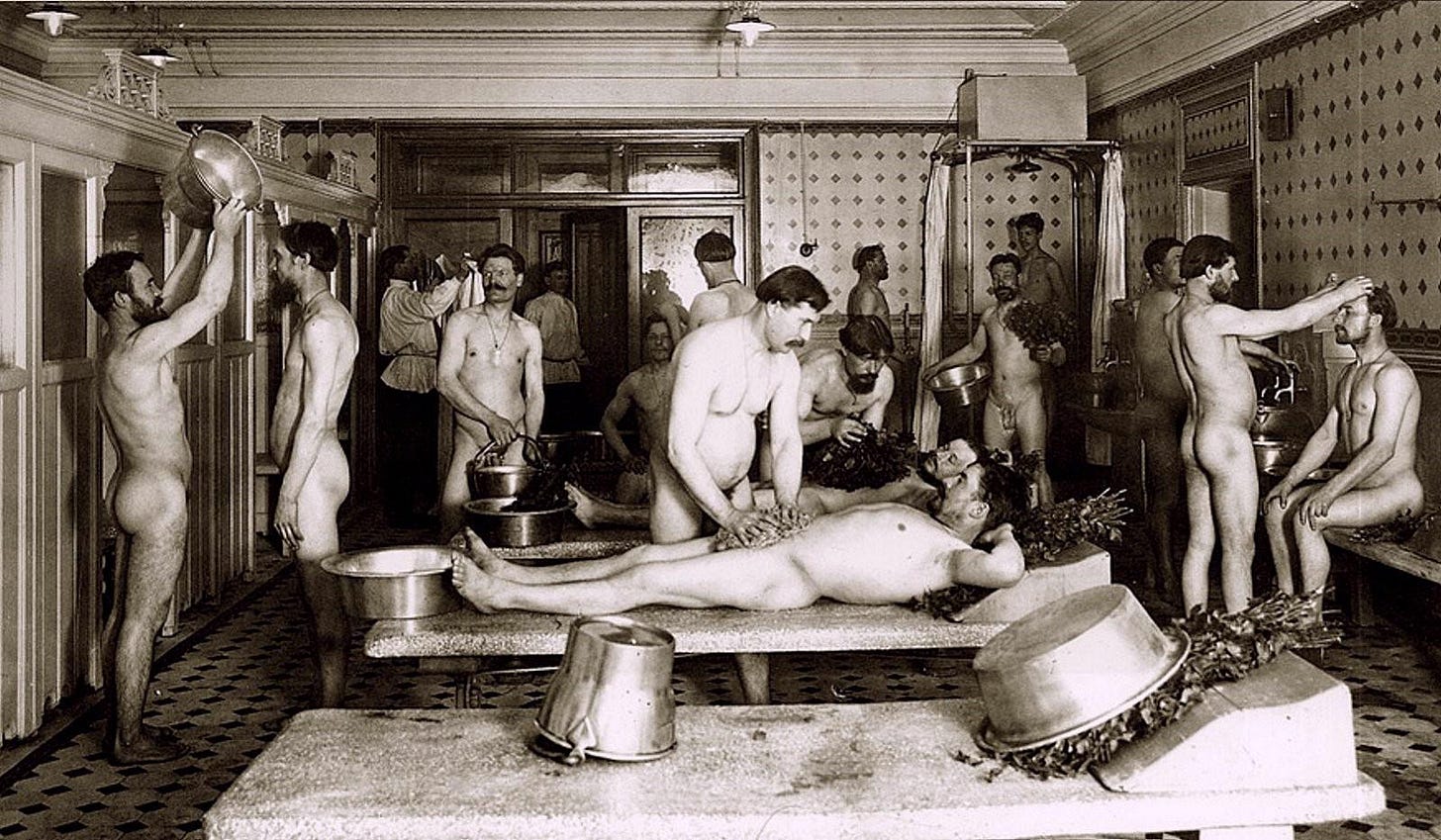

And then, of course, there were the bathhouses. Many were staffed by recent arrivals from the countryside who were only too willing to learn from their comrades how they could earn a few extra kopeks. Most of the capital’s established bathhouses had private rooms, where clients could go to be serviced by an attendant. While bathhouses served an important and traditional function, by the turn of the century some were notorious for being little more than male brothels. As one attendant noted, “all the money we got for that we put together and then divided it up on Sundays.” According to him, “all the attendants in all the baths in Petersburg” pursued this manner of gaining additional income.19

Perhaps the two most notorious of these St. Petersburg institutions were the Znamensky and Usachevikh Baths.20 The latter happened to be a favorite hunting ground for Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich. In his diary he noted his frequent visits and sexual encounters. Unfortunately for the closeted Grand Duke, he also suffered that which was most dreaded, being blackmailed by someone who learned his secret.

Like their male counterparts, St. Petersburg’s lesbian underground developed its own codes and systems for identification and meeting. For the most part they avoided street encounters, and seem to have relied on bordellos, where same-sex partners were to readily be found among the prostitutes. Many brothels encouraged the woman in their employ to engage in sexual relationships with their co-workers, believing that this would prevent them from falling in love with male clients and thus leaving the operation.21

In presenting a translation of Ruadze’s book I have treated it as a historical artifact. I have left his commentary and opinions intact however offensive they may be. Ruadze’s tone is condemnatory and filled with reprehensible homophobic venom. This reflects certain opinions contemporaneous with the book’s publication and must be read in that light. Ruadze tends to equate without question homosexuality with pedophilia, failing to note that the majority of pedophiles operating in Nicholas II’s St. Petersburg were in fact men preying on young girls. The trope of the homosexual as pedophile, though, clearly served Ruadze’s purposes, and he deployed it throughout the book.

For all its hyperbolic homophobia, Ruadze’s book is essentially factual, but this presents us with another problem. While he refers to actual locations in St. Petersburg by name, he cloaks the identities of those under discussion behind a string of pseudonyms. If we assume, as seems safe, that the individuals described in of K sudu! represent actual personages it is natural to seek out their true names. But I confess that here I am at something of a loss. I would therefore love to hear from readers with their thoughts and ideas which might help shine some light on the mysteries which the book contains.

Ruadze’s Introduction to K sudu!

Invisibly and secretly, homosexual vice was maturing under the guise of ostentatious decency.

Everyone knew of this existence, but no one had the courage to point openly to its followers and the disastrous consequences that they carried. But there was a modest journalist in Germany, Harden (Maximilian Harden, 1861-1927, who publicly exposed Philipp, Prince Eulenburg and other aristocrats and officials as members of a secret homosexual clique surrounding Kaiser Wilhelm II), who fearlessly exposed the all-powerful Prince Eulenburg. How the classic “Hannibal at the gates” has affected Germany’s ruling circles. The bureaucracy is hurriedly attempting to eliminate the powerful responsible for the question being suddenly raised.

It is no secret to those who have visited Germany, and especially Berlin, that thousands belong to this “sect” and that this vice is deeply ingrained, in many with positions vital to the operation of the state machinery. But why delve further into the morals of Germany and fear for its future when in our Russia, in our magnificent capital on the Neva, homosexual vice stands on no less solid ground?

It is unlikely that anyone living in St. Petersburg has a clear idea of the dimensions that homosexual vice has assumed in our country.

To take this properly into account, it is only necessary to examine our streets.

Streets are the mirror of social mores.

Where did these suspiciously dapper young men come from, nervous and drunk, apparently and day after day waiting for something in studied idleness? Where did these well-groomed gentlemen come from, with the stamp of lordship on their entire imposing appearance, with their overwhelming aristocratic surnames? What are they looking for in the public and Tauride Gardens, and what can connect them with the street, with its typical representatives: hooligans, creatures, artisans without a home and other people who seem to have no fixed occupations?

Here you are reminded of the details of the homosexual processes.

Bah! Yes, these are people who, like Prince Eulenburg, do not distinguish between themselves and the common people, and many things become clear in your mind, and if you are a father who has teenage sons then an involuntary horror seizes you and you hurry away from the street and most importantly take your children to a safe place.

“Detective” literature has flooded the book market, directing the child's imagination into the realm of fantastic detective work with his notorious hero [Sherlock] Holmes, so that his mind is already open to the vultures who lay lurking to corrupt his soul and his body.

Now that society has been awakened by the terrible warning cry of the Eulenburg trial it seems to me that this is the most favorable moment to bring to light, as much light as possible, the St. Petersburg homosexuals in our midst.

Chapter One: “Mademoiselle Shabelskaya”

All sorts of sores and ulcers fester in the stone boxes without air and light, called houses by incorrigible optimists.

In one of these stone boxes lives the most purulent, the most disgusting sore, “Mademoiselle Shabelskaya.” I know, reader, that you already have a picture of a bent, disfigured old woman thin as a stick but you are mistaken. “Mademoiselle Shabelskaya” is a thirty-year-old, tall blonde man who wears pince-nez, is always exquisitely dressed, and displays pretentious good manners.

According to his passport, “Mademoiselle Shabelskaya” is from Kolpino and his real surname is “Lendorf,”

What does “Mademoiselle Shabelskaya” do, you may ask, that is such an offense to civic life? It is a complicated question, starting with this strange alias.

“Mademoiselle Shabelskaya” is a commission agent for homosexual depravity, a brothel keeper, and a sworn debaucher of teenagers, who lives on the pay of a professor like himself.

It is impossible to say exactly why he took the name “Mademoiselle Shabelskaya.” The most plausible explanation is that about eight years ago he served as a weekend actor in the theater of E. A. Shabelskaya.

In the circle of homosexuals, it is customary to give each other nicknames, and “Mademoiselle Shabelskaya” is one of its pillars.

You can meet “Mademoiselle Shabelskaya” from 5 o'clock until closing time in the Passage. This is his main ground, where he makes a daily review of the youths he has recruited from the edges of our Russian youth.

At the same time, representatives of the homosexual “society” are also present at the review as interested persons, in front of whom the recruits make a “short gallop.” There is also an exchange where the preferences of the various males are given. After this daily parade, there is tea at the Café de Paris [a restaurant located in the basement of the Passage] and then, at your discretion, you can go to the brothels run by “Shabelskaya,” “Eichenfeld,” or “Kurochkin,” or go to the beloved Znamensky Baths.

But the greatest of “Shabelskaya’s” hunting grounds is on the sidewalks near schools, workshops, and other places where teenaged boys can be found. Watching the inimitable grace and skill with which he makes “interesting acquaintances” with boys, you involuntarily come to the conclusion: here is a Man who has found his true calling!

It is not for nothing that when the actor “Dov” needed a “boy,” he turned to “Shabelskaya” who took a certain “Rogalev” from an educational institution.

“Rogalev,” where are you now? Please respond to publicly confirm the “genius” of “Mademoiselle Shabelskaya.”

Or tell us who, for example, dug up “Ogarkov's” one-of-a-kind demimonde “Zhenya?” Ask any of the homosexuals and they will answer you without hesitation: “Well, of course, ‘Shabelskaya.’”

“Lendorf's” photograph is kept in the police department, but probably as a relic, because so far there has been no evidence of the involvement of the police investigating the work of “Shabelskaya.”

And this, after all, is amazing!

Chapter Two: “Eichenfeld’s” Brothel

On Malaya Konyushennaya Street, in an annex to a small but comfortably furnished apartment, the modest “Eichenfeld” family settled about three years ago. In addition to an older brother “Max” and his sister “Alice,” a younger brother named “Alfred” also lived in this apartment.

The residents of the house did not notice anything suspicious in the apartment of the newcomers. However, almost from the very first day, young people of various appearances began to visit “Max.”

“These are my brother's patients,” “Alice” reassured the house administration, and everything went on without problem.

From time to time, the apartment was lit up at night to be as bright as day when “Max” held his evenings. To an observant person, it might seem a little suspicious that the exclusively male element predominates at these evenings, but who needed to observe the life of a modest Livonian family?

The longer “Max Eichenfeld” lived in St. Petersburg, the more his “business” increased. After a while residents of the house could see his younger brother “Alfred” taking driving lessons in his new shiny motorcar in the yard.

“’Max’ is doing well,” the neighbors said to each other, “and so bought a motorcar for his brother.”

So, from the outside, the “Eichenfeld” family seemed invulnerable.

In the eyes of the residents, “Max” gained special attention by meeting young people in cocked hats. “They are all real gentlemen,” reasoned the janitor, “nothing like Mr. ‘Eichenfeld,’ who is a petty bourgeois, but he has very important acquaintances.”

But while the tenants and the janitor had the most rosy opinion of the newly-arrived family, “Max Eichenfeld” was in fact doing the same thing as “Shabelskaya,” only his activity was limited to operating a brothels, and he undertook special “commissions” only accidentally and if he received extra pay.

In the person of “Eichenfeld” we are dealing with a brothel keeper who is very popular in homosexual circles.

Why he was dismissed as a mere “foolish German” has its own logical explanation.

There are people who, under the guise of feigned “stupidity,” conceal the darkest deeds that require great cunning. “Stupidity” serves them as a protective shell, making them invulnerable to the prying eyes. And the homosexuals turned out to be bad psychologists, having christened him as “stupid,” which so little, in fact, fit with his way of acting.

“Max Eichenfeld” has a strong and wealthy patron in the homosexual “world,” a certain “Mr. C.,” the brother of a dignitary. In the service of his “pleasant amusements,” he did not disdain to deliver “newcomers,” as the circle calls the victims of this “sect.”

In his apartment, representatives of society had “dates” with the demimonde and just casual acquaintances picked up somewhere in the Passage.

Beer and other “strengthening” drinks could also be obtained at impossibly expensive prices. In a word, it was a “shelter of homosexual love” au naturel.

If we add to this the paid masquerades arranged periodically by “Max,” where 2 rubles were charged from each person, then the circle of his activities can be considered complete.

But “Max Eichenfeld” was also known in another way, namely as a splendid dressmaker who created clothing for the homosexuals. They ordered toilettes from this enterprising gentleman, a jack of all trades.

At the beginning I spoke of the motor which so impressed the “Eichenfeld” neighbors, and I can say that it was not cheap for young “Alfred,” and that “Max” played the most vile part in it.

His masquerades will have to be returned to later! In the meantime, enough about this rare specimen from the picturesque surroundings of “cultured” Riga.

To be continued…

Source Notes

1. Healey, 107.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid., 78.

4. http://community.middlebury.edu/~moss/RGC2.html.

5. “Moonlight Love,” by Professor Igor Kon, at www.Gay.Ru; Healey, 22.

6. Healey, 22.

7. http://community.middlebury.edu/~moss/RGC2.html; “Moonlight Love,” by Professor Igor Kon, at www.Gay.Ru; Healey, 81-82.

8. “Moonlight Love,” by Professor Igor Kon, at www.Gay.Ru.

9. Healey, 96.

10. Ibid., 92-93.

11. Ibid., 101.

12. Ibid., 102.

13. Ibid., 101.

14. Ibid., 107.

15. “Moonlight Love,” by Professor Igor Kon, at www.Gay.Ru; Engelstein, 158; Healey, 109.

16. Healey, 39-41.

17. Ibid., 31-32, 37.

18. Ibid., 32-33.

19. Ibid., 27.

20. Ibid., 33. The Znamensky Baths were situated in houses at Nos. 51 and 53 Znamenskaya Street and opened in 1851; the Usachevikh Baths was located on the Moika.

21. Ibid., 52.

Bibliography

Engelstein, Laura. The Keys to Happiness: Sex and the Search for Modernity in Fin-de-Siècle Russia. Ithica, NY: Cornell University Press, 1994.

Healey, Dan. Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Kon, Igor. “Moonlight Love.” At www.Gay.Ru