By Greg King

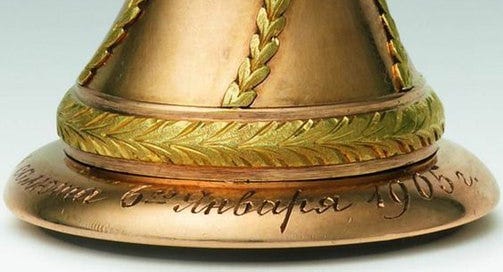

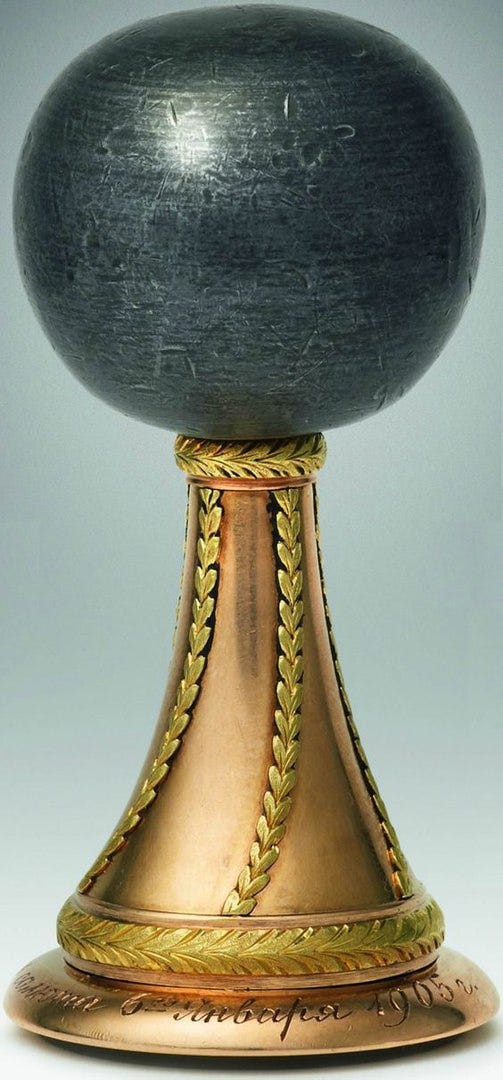

It stands just 2.5 inches tall. At first glance, it seems to be an ordinary, though exquisite, seal. Crafted by Henrik Wigström for the St. Petersburg workshop of jeweler Karl Fabergé, it is composed of a trumpet-shaped body in burnished red gold and embellished with trailing laurels of chased green gold. The seal, of white chalcedony, bears the insignia of Nicholas II and the Order of St. Andrei. And surmounting it all is a steel sphere, slightly flattened. It would seem to be an odd choice of ornament for so delicate an objet d’art, but an inscription circling the base tells the story: “In Memory of the Salute of January 6, 1905.”(1)

I think I first saw this seal in the early 1980s, in a book about Fabergé. I don’t think it really captured my interest at the time – I was more interested in the Imperial Easter Eggs and Fabergé’s flashier items. But in one of those bizarre bits of synchronicity that occasionally crop up, I came across it again, this time in real life, in 1997.

The Blessing of the Waters was one of many ceremonies marked by the Russian Imperial Court. It always took place on Epiphany, January 6, and was an inheritance from the Byzantine Empire. Meant to commemorate Christ’s baptism in the River Jordan, the ceremony – as undertaken by the Russian Court – was a fusion of religious and temporal power, with the hierarchy of the Orthodox Church and the sovereign participating in a reenactment. A hole was cut in the frozen Neva River, and the clergy blessing the water below by making the Sign of the Cross three times. The first blessing was in the air, and a second in the actual water, into which a cross and the troja, three joined candles, were also dipped. A small quantity of the blessed water was collected in an ornamental vessel; the celebrants then approached the officiant, kissing the cross and being sprinkled by the priest. Throughout a liturgy was sung, and the ceremony concluded with an artillery salute, a review of the Imperial Guards, and a celebratory luncheon for members of the Imperial Family, high officials, the clergy, and members of the diplomatic corps.

In 1905, Epiphany fell in the middle of the ongoing Russo-Japanese War and increasing unrest. Nicholas II had been staying in the Alexander Palace at Tsarskoye Selo but at 9 that morning he and Empress Alexandra boarded the Imperial Train and traveled to St. Petersburg. At the Winter Palace, they were joined by most members of the Imperial Family.(2)

Events of Thursday, January 6 followed the same, precise pattern. A Great Procession, peopled by the Romanovs and court dignitaries, passed in state through the halls of the Winter Palace from the Malachite Hall to the Palace’s Cathedral of the Savior-Not-Made-By-Hands, where a liturgy was held. Vladimir Gurko, who was present that January 6 in 1905, later wrote: “This ceremony was marked by its traditional dignity and splendor. A few small units of the guards, quartered in St. Petersburg and its vicinity, and some other troops were drawn up in the halls of the palace on both sides of the Imperial march to the church. The gentlemen and ladies privileged to attend the reception were ranged in pairs along the Concert Hall to form the head of the Emperor’s procession. The masters of ceremonies, walking on both sides of this group, were as usual vainly striving to maintain a semblance of order and a straight line. Then they tapped on the floor with their long staffs, adorned with blue St. Andrei ribbons, to announce the appearance of the Emperor. The doors of the Malachite Room, where the members of the Imperial Family usually gathered before their appearance, were thrown open, and the Emperor, preceded by the Minister of the Imperial Court, made his entrance with the Empress. Behind them the rest of the Imperial Family walked in pairs to the strains of the Preobrazhensky regimental march….It was a clear day, with sunlight flooding the huge, splendid halls of the Palace; the glimmer of the gold lace on the uniforms and of the formal court dresses of the ladies – all this made a wonderful and unforgettable picture, which fascinated even those who were accustomed to these ceremonies and made one forget temporarily the unhappy war, its series of defeats, and the troubled, uncertain conditions in the country. It was but natural, therefore, that on January 6, 1905, the Emperor, whose face since the beginning of the War had worn a sadder expression than ever before, seemed more composed and cheerful.”(3)

At the end of the liturgy, the procession returned through the Palace, dividing in the Field Marshal’s Hall. The Empresses and Grand Duchesses, accompanied by their respective suites, walked through the Anteroom, the Nicholas Hall, and the Concert Hall to the Malachite Hall, where they would watch the ceremony taking place on the Neva Quay through the tall windows. The Emperor and male members of the Imperial Family, along with the courtiers, clergy, and military attendants, processed down the Jordan Staircase, named for its role in this very ceremony.

“At a given moment,” Gurko wrote, “the troops with their colors left the Palace and in resounding, measured tread proceeded down the great Jordan Staircase to the quay of the Neva to take their appointed places there. When Mass in the Palace chapel ended, church processions from all the St. Petersburg churches gathered by the Neva. Innumerable church banners and the gold-woven, brocaded robes of the clergy, shimmering in all the colors of the rainbow, made the Palace quay into one huge church gathering, surrounded by military units. It was one of those religious and military ceremonies which distinguished the Russian Imperial Court from the rest of the European courts and in which the spirit of the old Muscovite empire, permeated with religious and secular powers, which complemented each other and formed one whole, was still alive.”(4)

At 11:45 AM, and emphasizing the religious nature of the ceremony, Metropolitan Anthony of St. Petersburg led the procession from the Winter Palace, followed by bishops, archimandrites, and priests attired in festive dalmatics, stoles, and copes studded with pearls and diamonds. As they walked, they swung smoking censers of incense that perfumed the chill air with the rich aromas of cloves and rose oil. The Emperor, Grand Dukes, and high-ranking courtiers, followed the clergy down the Jordan Staircase and out of the Palace.(5)

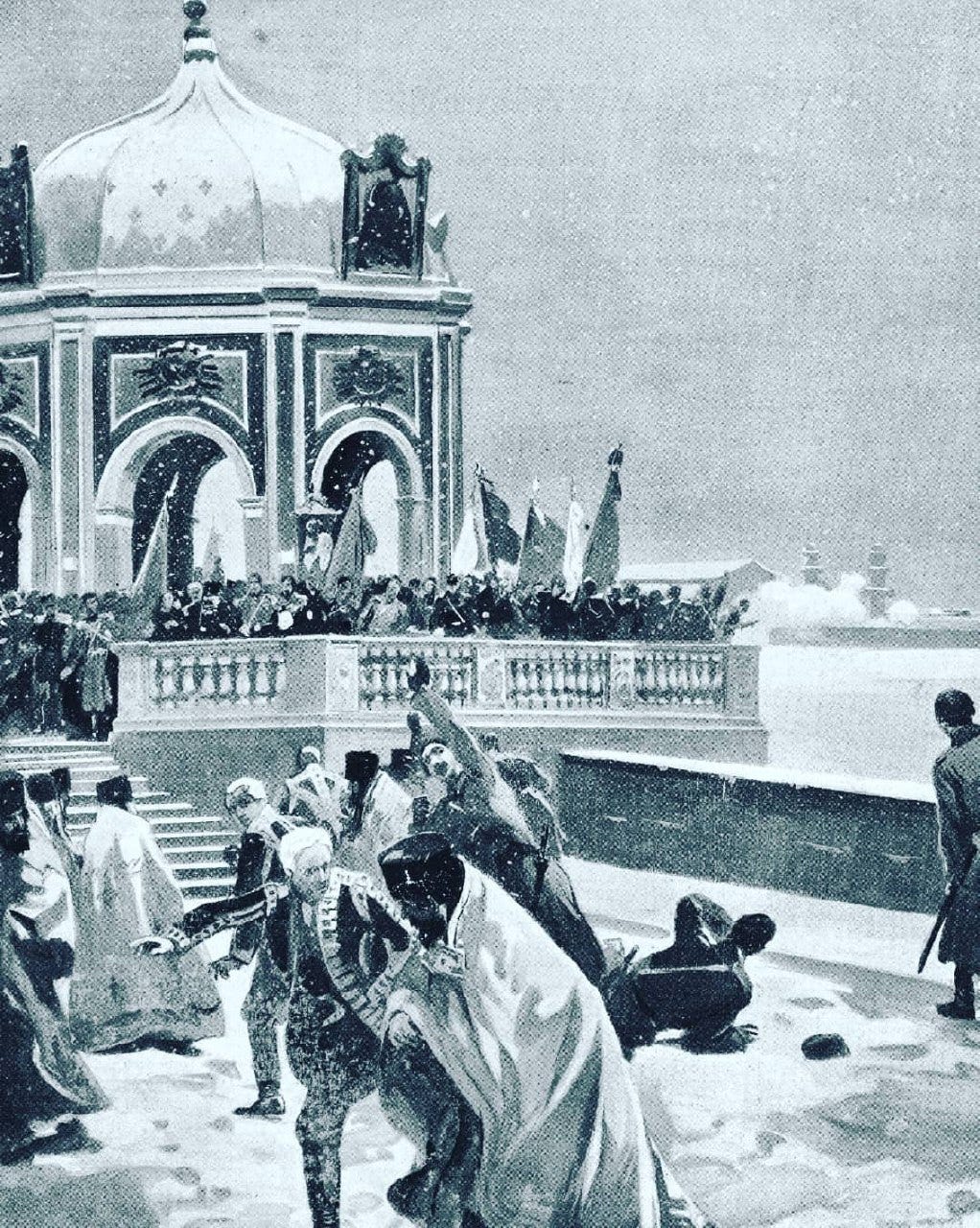

Along the Neva embankment, the granite quay was covered with a strip of crimson carpet, leading from the Winter Palace to the river’s edge. Here, a temporary octagonal wooden pavilion was built over the Neva River. Octagonal in design, it featured open arches, decorative heraldic shields, and was capped by a dome displaying four large icons in golden frames. There were prayers and a liturgy before the Metropolitan blessed the water and dipped a cross in a hole made in the ice.

The moment was always marked by artillery salutes, fired from the guns of the Fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul directly across the Neva and from a battery stationed on the Strelka of Vasilevsky Island in front of the Exchange. On this particular occasion, the 17th Battery of the First Horse Guards Artillery was in charge of the guns on the Strelka. They had practiced their salutes two days earlier without incident. But on the day of the actual ceremony, one of the guns had been loaded with live ammunition instead of a blank shell. “Detonation after detonation rang out over the river,” recalled Vladimir Gurko. “Then suddenly they were followed by another, more rolling and peculiarly warlike in sound, recognizable to even an untrained ear. Those present looked at each other with anxiety and amazement.”(6)

Aimed directly toward the Winter Palace, the charge boomed out, its scattered buckshot flying through the air and smashing into the pavilion, the quay, and the palace itself. Sergeant-Major Salov of the Naval Cadet Corps was on the quay, holding a mast bearing the Marine standard when a piece of shot hit the flagpole, snapping it in half.(7) Another piece of shot struck a policeman, ironically named Romanov, in the eye, killing him, and a half-dozen others were wounded; pieces of lead pierced the dome of the wooden pavilion; and shots hit the façade of the Winter Palace, pocking columns and smashing through windows.(8)

A. I. Verkhovsky, then serving as a Kammer Page, was standing near the Emperor when the shots rang out. “At almost the same time,” he remembered, “a rattle of broken glass was heard above us in the Palace windows. There was a loud crack from the dome of the pavilion, and a large fragment of wood fell at the Emperor’s feet.”(9) Guards officer Anatoli Mordvinov was also on the quay. “Simultaneously with the sound of the salutes, I heard some cracking on the ice and smashing from above. I felt something sweep past me. I involuntarily looked up, thinking that it was probably the falling debris from an unsuccessfully launched shot. But I did not notice any debris, just as I did not notice any embarrassment among the others – the prayer service continued to be performed in the same solemn order. The Emperor calmly venerated the cross and leisurely, with his usual gait, walked around the sprinkled banners and standards with the Metropolitan.”(10)

Maria Georgievna, married to Grand Duke George Mikhailovich, was with the two Empresses and the other ladies of the Imperial Family in the Malachite Hall, watching the scene below through the windows. “Strangely enough,” she remembered, “none of us remarked anything unusual.”(11)

Members of the diplomatic corps and foreign guests watched the ceremony through the windows of the Nicholas Hall overlooking the Neva River. Shrapnel shattered two of the Hall’s windows.(12) D. N, Lyubimov, an official with the Ministry of Internal Affairs, recalled: “At the third or fourth shot, a crack of broken glass was heard in an upper window. At the same time, something hit the rear wall, bounced off and rolled on the parquet of the hall. The ladies of the embassy, standing in front, were showered with small glass. They screamed and rushed back. In the next window, the same thing happened. Someone picked up one of the rolling balls – it turned out to be grapeshot. The well-dressed audience immediately fled away from the windows….Round holes were visible in the windows, leaving no doubt as to their nature: the shots were live.”(13)

Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden was in the Nicholas Hall when she “heard a tremendous crash of glass after the first loud report. To the intense surprise of all, we saw pieces of glass all over the floor.”(14) British Ambassador Sir Charles Hardinge, standing nearby, recorded that “two or three grapeshot passed through the windows from which we were looking, and having struck the walls were picked up in the room.”(15) British visitor Renee Elton Maud remembered: “Some fragments of shrapnel shells fell into out room and quite close to the group of people where I was standing, smashing the panes of glass of one of the windows, which were strewn all over the floor.”(16) And Vladimir Gurko, also in the Nicholas Hall, wrote: “One of the bullets, of the old-fashioned large type, after breaking a pane had hit one of the golden platters adorning the walls and felled it to the floor. As I happened to be standing nearby, I picked it up and passed it to some of the court officials standing by me.”(17)

Throughout, Nicholas II remained calm and continued the ceremony. At the end, the procession returned to the palace. “I noticed to my amazement,” remembered Anatoli Mordvinov, “that several of the windows in it were broken, and as I was going up the palace staircase with the others, I heard someone saying excitedly: ‘What a miracle that we all survived! After all, they fired at us with real combat grapeshot.” Later, Mordvinov went back to the quay to look at the pavilion: “Its entire bottom near the ice was densely riddled with grapeshot bullets. A lot of them got into the upper structure of the pavilion and into the dome.”(18)

After a military review and luncheon for the diplomatic corps, Nicholas II and Empress returned to Tsarskoye Selo. Although Nicholas had been outwardly calm during the incident, he later told his sister Olga Alexandrovna, “I knew that somebody was trying to kill me. I just crossed myself. What else could I do?”(19) And, to his valet, he declared, “Today they shot at me!”(20)

Everyone indeed suspected that this had been an assassination attempt. “It seemed like an attack on the lives of the Emperor and the high officials who were present in large numbers,” Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich wrote in his diary.”(21) Official Lev Tikhomirov recorded: “All the military unanimously declare that the events of January 6 were an obvious assassination attempt, and that there could be no such accident.”(22)

A special commission, under the direction of Grand Duke Sergei Mikhailovich as Inspector-General of the Artillery, was appointed to investigate the incident. This eventually decided that it had been an accident, caused through negligence: someone had inadvertently loaded a live round into one of the guns. “In the absence of any indications of any criminal intent in the case,” the decision read, “the shot that occurred can be explained with sufficient probability by non-compliance with the established rules in the handling of guns in the park and during salutation shooting.”(23)

Three of the officers in charge of the 17th Battery of the First Horse Guards Artillery whose gun had fired the live round, a Captain Davydov, Staff Captain Kartsov, and a Lieutenant Roth, were expelled from the Guards. All were sentenced to be imprisoned in the Fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul, Davydov for eighteen months, Kartsov for seventeen months, and Roth for sixteen months. Two other junior officers, gunnery lieutenants, were deprived of their ranks and received shorter sentences.(24)

And so to the Fabergé seal, a tangible reminder of that eventful January 6, 1905. In the summer of 1997, during a research trip, I spent a few days staying with Prince and Princess Michel Cantacuzène at their house in Rhode Island. One of the items on display in their living room was the Fabergé seal, sitting casually on a little table. I picked it up and examined it. The Princess insisted that it had been made for Misha’s father, who had picked up a piece of shrapnel that day. I didn’t question her on this point, but research has led to serious doubts about this tale. They certainly had the seal, but how it came into their possession remains a question.

The Prince’s father may well have picked up a piece of shrapnel that day: many people did so. On his way back to the Winter Palace, Nicholas II supposedly stopped and retrieved one of the lead pieces, saying, “I’ll keep this as a souvenir.”(25) Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich also picked up a piece of shrapnel: he showed it to Anatoli Mordvinov on the night of January 6.(26) So, too, did Vladimir Gurko, who retrieved his piece from the Nicholas Hall. Grand Duchess George later wrote: “When the Emperor and the Grand Dukes returned, one of them came up to me and showed me a bullet and a bit of broken wood from the pavilion which he had collected.”(27)

The usual story, though, attributes this particular piece of shrapnel to Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich, who is said to have picked it up and had it mounted atop the Fabergé seal, then presenting it to Nicholas II as a souvenir of the day.(28) This seems to be the most likely explanation. Although numerous people are known to have picked up pieces of shrapnel that day, the evidence suggests that this bit originated with a member of the Imperial Family. Only a member of the Imperial Family would have been able to commission a seal bearing Nicholas II’s crest, and it is the sort of thing that the militaristic Nicholas Nikolaevich, with his somewhat characteristic lack of tact, might well have regarded as an amusing souvenir.

How the Cantacuzènes acquired the seal is unknown, but they certainly had it in their possession. After the Prince’s death it remained with his widow and after her death it came on the market. It was apparently sold at auction in 2012 for a reported $620,000.(29)

With thanks to Nick Nicholson for additional information.

Source Notes

1. Snowman, 125; https://little-histories.org/2024/02/21/illjustracija-proisshestvie-v-den-kreshhenija-gospodnja-u-zimnego-dvorca-6-janvarja-1905-goda-1905-god/.

2. https://epoha-nikolaya-2.ru/vystrely-na-iordane/.

3. Gurko, 339-40.

4. Ibid., 340.

5. Novoe Vremya, January 7, 1905.

6. Gurko, 341.

7. https://pantv.livejournal.com/1360215.html.

8. Novoe Vremya, January 7, 1905; San Francisco Call, January 20, 1905; Verner, 150.

9. https://epoha-nikolaya-2.ru/vystrely-na-iordane/.

10. Mordvonov, 51-52.

11. Grand Duchess George, 117. In his authorized biography of Ncholas II’s sister Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, author Ian Vorres wrote that shrapnel “smashed a window in the palace – a bare few yards away from the Dowager Empress and the Grand-Duchess – and glass splinters went all over their shoes and skirts.” See Vorres, 120. This in error, as the damage to the Winter Palace was limited to the Nicholas Hall, which was separated from the Malachite Hall by the Concert Hall.

12. Novoe Vremya, January 7, 1905.

13. https://epoha-nikolaya-2.ru/vystrely-na-iordane/.

14. Buxhoeveden, 208.

15. Hardinge, 112.

16. Maud, 110.

17. Gurko, 341.

18. Mordvonov, 51-52.

19. Vorres, 120.

20. Bogdanovich, diary entry of January 8. 1905.

21. Sablinsky, 198.

22. https://epoha-nikolaya-2.ru/vystrely-na-iordane/.

24. https://epoha-nikolaya-2.ru/vystrely-na-iordane/; https://pantv.livejournal.com/1360215.html; https://little-histories.org/2024/02/21/illjustracija-proisshestvie-v-den-kreshhenija-gospodnja-u-zimnego-dvorca-6-janvarja-1905-goda-1905-god/; Gurko, 341.

25. Weber-Bauler, 122.

26. Mordvinov, 52.

27. Grand Duchess George, 117.

28. Snowman, 125.

29. https://little-histories.org/2024/02/21/illjustracija-proisshestvie-v-den-kreshhenija-gospodnja-u-zimnego-dvorca-6-janvarja-1905-goda-1905-god/.

Bibliography

Books

Bogdanovich, Alexandra. Tri poslednikh samoderzhtsa: Dnevnik, A.V. Bogdanovicha. Moscow: Gosizdat, 1924.

Buxhoeveden, Baroness Sophie. Before the Storm. London: Macmillan 1938.

George, Grand Duchess (Maria Georgievna). A Romanov Diary. New York: Atlantic International, 1988.

Gurkov, Vladimir. Features and Figures of the Past. New York: Russell & Russell, 1970.

Hardinge, Sir Charles. Old Diplomacy: The Reminiscences of Lord Hardinge of Penshurst. London: Murray, 1947.

Maud, Renee Elton. One Year at the Russian Court, 1904-1905. London: John Lane, 1918.

Mordvinov, Anatoli. Iz opyta: vospominaniya ad’yutantskogo kryla imperatora Nikolaya II. Moscow: Kuchkovo Pole, 2014.

Sablinsky, Walter. The Road to Bloody Sunday. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976.

Snowman, A. Kenneth. Carl Fabergé, Goldsmith to the Imperial Court of Russia. New York: Greenwich House, 1983.

Verner, Andrew. The Crisis of Russian Autocracy: Nicholas II and the 1905 Revolution. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Vorres, Ian. The Last Grand Duchess. London: Hutchinson, 1964.

Weber-Bauler, Leon. From Orient to Occident. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1941.

Newspapers

Novoe Vremya

San Francisco Call

Internet Resources

https://little-histories.org/2024/02/21/illjustracija-proisshestvie-v-den-kreshhenija-gospodnja-u-zimnego-dvorca-6-janvarja-1905-goda-1905-god/

https://epoha-nikolaya-2.ru/vystrely-na-iordane/