Being close to Halloween, a little diversion from the Romanovs…

Every autumn I usually revisit a few of my favorite classic novels with supernatural and horror themes. H. P. Lovecraft always figures in, culminating with his Case of Charles Dexter Ward. This year, though, I’ve also been reading the works of William Hope Hodgson. If you’re steeped in this particular genre you probably recognize the name, but he is not well known today. Yet only Edgar Allan Poe has had such an influence on horror-fantasy literature. Coupled with his tragically short life, this makes him an appropriate topic for a Halloween-themed article.

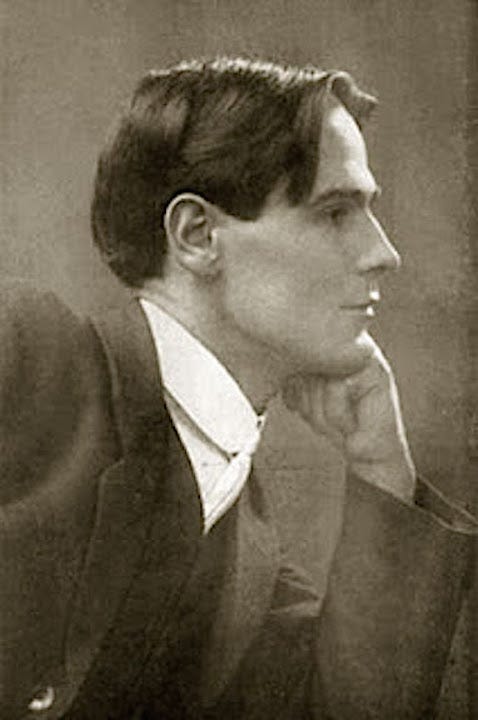

William Hope Hodgson was born on November 15, 1877, in a small village in Essex, England, one of 12 children of an Anglican clergyman and his wife. The family moved frequently, and finances were tight. At age 13, Hodgson ran away from school and a year later joined the Royal Navy as a cabin boy.(1) As one biographer noted, “His relatively short height and sensitive, almost beautiful face made him an irresistible target for bullying seamen.” Yet he proved himself, winning a medal after saving another sailor who had fallen into shark-infested waters off New Zealand.(2) His time at sea would later influence many of his macabre stories.

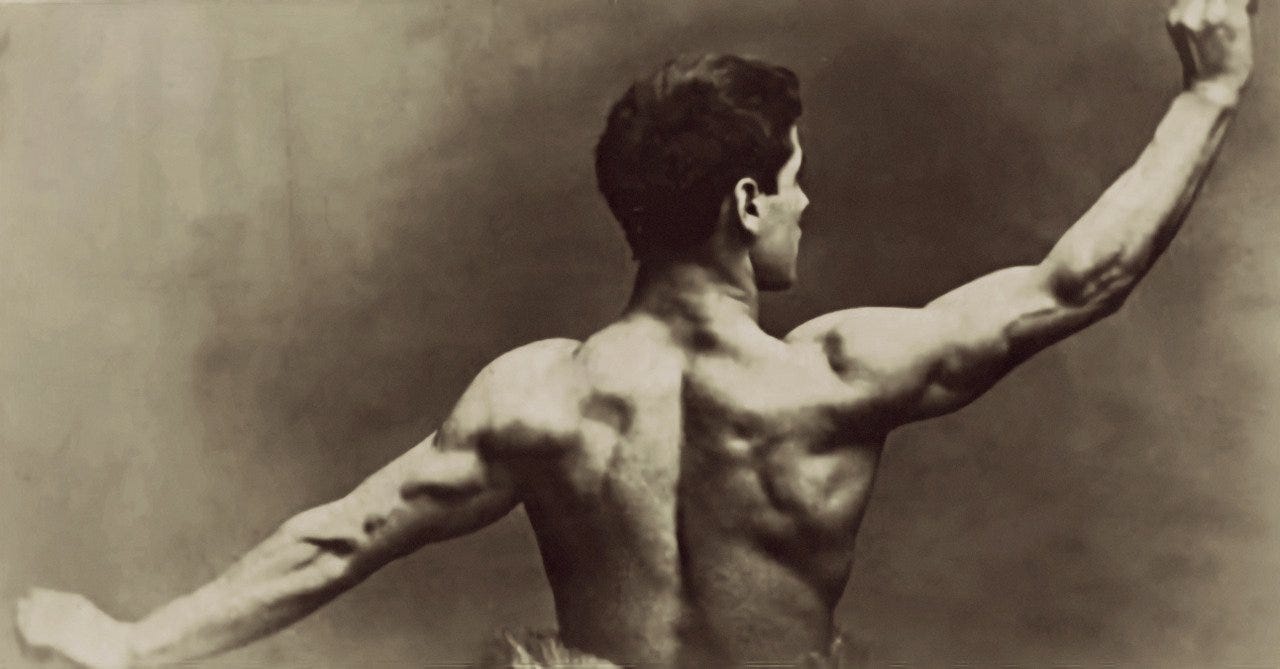

In 1899, after leaving the Navy, Hodgson opened the School of Physical Culture in Blackburn, England, where he promoted weightlifting and exercise training. He cultivated publicity, displaying his muscled torso for photographs and writing articles on physical fitness. In 1902, he attended a performance by magician Harry Houdini and accepted his challenge for an audience member to bind him so tightly that he could not escape. Hodgson, Houdini later complained, had done the job too well, making it nearly impossible for him to free himself.(3)

Although his formal education had been spotty, Hodgson began reading voraciously and decided that he wanted to become a writer. His first short story, The Goddess of Death, was published in The Royal Magazine in 1904; more short stories followed. Hodgson – like Lovecraft – tended to write in intricate, archaic language, with extensive sentences and occasionally rambling digressions that nonetheless managed to capture a sense of menace and unseen terror. In 1904 came the first of his Sargasso Sea stories, tales awash with strange happenings and imaginary horrors lurking beneath the seaweed-cloaked surface. The Sargasso Sea stories continued on for nearly a decade, appearing in prominent British and American magazines and winning Hodgson a reputation as a master of the macabre. 1907 saw publication of The Voice in the Night, widely considered to be Hodgson’s greatest short story, in which a shipwrecked couple find themselves plagued with a strange, living fungus that is transforming them into monsters.

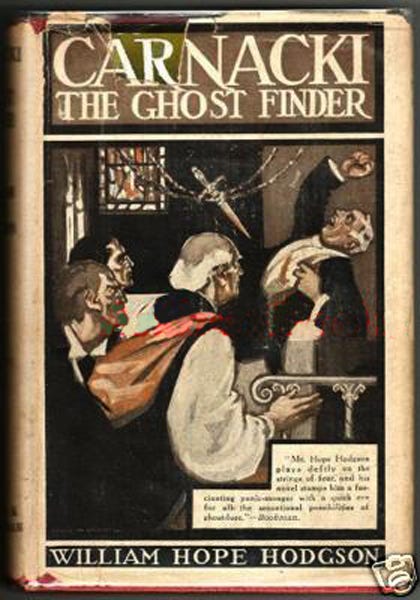

Starting in 1910, Hodgson began writing a series of occult stories detailing the experiences of an investigator named Thomas Carnacki, dubbed “the Ghost Finder.” These resemble a sort of hybrid between two modern, beloved television series, Kolchak: The Night Stalker and the X-Files, in which various supernatural forces appear. Hodgson created an entirely new mythos to surround these tales, with strange, mysterious books containing rituals and incantations to fight evil. There were mysterious murders; ghostly apparitions; deserted mansions plagued with strange paranormal activity; rooms plagued with eerie fungal growths; and even a phantom horse. The great mystery writer Ellery Queen described Carnacki as a “ghost-breaker after Houdini’s heart” and cited the stories as pivotal works in detective fiction.(4)

Hodgson published his first novel, The Boats of the Glen Carrig, in 1907. Like his Sargasso Sea stories, this involved the crew of a haunted ship, left stranded on a deserted island where they encounter unspeakable monsters and face descendants of men trapped for centuries under the ocean who periodically emerge to terrorize them. The novel was hailed as a supremely frightening book; contemporary critics even compared it favorably to Frankenstein and Dracula.(5)

The House on the Borderland followed in 1908. This told the story of a man living in isolation with his dog at a strange, remote house in Ireland. “There had stood a great house in the center of the gardens,” the story began, “where now was left only that fragment of ruin. This house had been empty for a great while; years before his, the ancient man's, birth. It was a place shunned by the people of the village, as it had been shunned by their fathers before them. There were many things said about it, and all were of evil. No one ever went near it, either by day or night. In the village it was a synonym of all that is unholy and dreadful.” Related through entries in a diary found by two fishermen, the tale includes travels into another dimension populated by horrific monsters; unexplained phenomena; and culminates in a terrifying entry in which creatures begin to emerge from beneath the house as the unnamed writer desperately records his last words. The novel was among the first to explore the idea of Cosmic horrors, which later became a hallmark of the work of H. P. Lovecraft, who called The House on the Borderland the greatest of Hodgson’s works.

In 1912, Hodgson published his last novel, The Night Land. Set in the distant future, it told of a world where the sun was dead and night everlasting. The few remaining people endure nightmarish happenings at the hands of other-worldly monsters at the edge of the universe called The Watchers. The London Magazine praised it as “the most notable book that has been the light of day for many years,” while Vanity Fair remarked, “In every sense remarkable….Once it has been taken up one cannot leave it for any length of time.” And H. P. Lovecraft would later describe The Night Land as “one of the most potent pieces of macabre imagination ever written.”(6)

In February 1913, Hodgson married Betty Farnworth; both were thirty-five, somewhat past the usual age for first marriages. Like her husband, Betty wrote for a living, authoring an advice column for the women’s magazine Home Notes, but she gave up her career after marriage. Money was tight: despite his three novels, numerous articles, and short story collections, Hodgson was perpetually in debt. In late 1913 the couple moved to France, where the cost of living was less, but when World War I erupted, they returned to England.

Hodgson had hated his time at sea; rather than enlist in the Navy again, he joined the Army, receiving a commission as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 171st Battery of the Royal Artillery Brigade. In 1916 he was seriously wounded when he was thrown from his horse while in France. His jaw was broken and he suffered from a head injury, which meant his mandatory return to England. After six months, though, he re-enlisted and returned to France as a Lieutenant. To his mother, Hodgson wrote: “The sun was pretty low as I came back, and far off across that desolation, here and there they showed, just formless, squarish, cornerless masses erected by man against the infernal Storm that sweeps forever, night and day, day and night, across that most atrocious Plain of Destruction. My God! Talk about a Lost World, talk about the end of the World, talk about The Night Land – it is all here, not more than two hundred odd miles from where you sit infinitely remote. And the infinite, monstrous, dreadful pathos of the things one sees, the great shell-hole with over thirty crosses sticking in it; some just up out of the water, and the dead below them, submerged….If I live and come somehow out of this (and certainly, please God, I shall and hope to), what a book I shall write if my old ‘ability’ with the pen has not forsaken me.”(7)

Hodgson was at the Fourth Battle of Ypres when, on April 19, he suffered a direct hit from an artillery shell and was literally blown to pieces. He was only forty.(8)

Only a few scattered fragments remained, and they were buried in an unmarked grave on the eastern slope of Mont Kemmel in Belgium. The Commanding Officer wrote to Hodgson’s mother: “I cannot express my deep sympathy for you in your great bereavement. I feel it most terribly myself, and so do all the other officers and men of the battery. He was the life and soul of the mess—always so willing and cheery. Of his courage I can give no praise that is high enough. He was always volunteering for any dangerous duty, and it was owing to his entire lack of fear that he probably met his death. He had performed wonders of gallantry only a few days before, and it is a miracle that he survived that day. I myself am deeply grieved, having lost a real, true friend and a splendid officer.”(9)

Had Hodgson survived, he would undoubtedly have continued his career in fantastic fiction, further cementing his name as a leading influence in the genre. It took several decades for his work to be rediscovered. Among his most important devotees was H. P. Lovecraft. In November 1925, Lovecraft accepted a commission to write an article for the magazine The Recluse on “elements of terror and weirdness in literature.” That article included discussion of Algernon Blackwood, M. R. James, Ambrose Bierce, Arthur Machen and, significantly, William Hope Hodgson.(10)

Lovecraft described Hodgson’s work as “of rather uneven stylistic quality, but vast occasional power in its suggestion of lurking worlds and beings behind the ordinary surface of life….Despite a tendency toward conventionally sentimental conceptions of the universe, and of man's relation to it and to his fellows, Mr. Hodgson is perhaps second only to Algernon Blackwood in his serious treatment of unreality. Few can equal him in adumbrating the nearness of nameless forces and monstrous besieging entities through casual hints and insignificant details, or in conveying feelings of the spectral and the abnormal in connection with regions or buildings. In The Boats of the Glen Carrig (1907) we are shown a variety of malign marvels and accursed unknown lands as encountered by the survivors of a sunken ship. The brooding menace in the earlier parts of the book is impossible to surpass…. The House on the Borderland (1908), perhaps the greatest of all Mr. Hodgson's works, tells of a lonely and evilly regarded house in Ireland which forms a focus for hideous otherworld forces and sustains a siege by blasphemous hybrid anomalies from a hidden abyss below. The wanderings of the Narrator's spirit through limitless light-years of cosmic space and Kalpas of eternity, and its witnessing of the solar system's final destruction, constitute something almost unique in standard literature. And everywhere there is manifest the author's power to suggest vague, ambushed horrors in natural scenery.”(11)

A decade later, in the February 1937 issue of Phantagraph, Lovecraft authored an article called The Weird Work of William Hope Hodgson. He described “the remarkable work of an author relatively unknown in this country, yet actually forming one of the few who have captured the illusive inmost essence of the weird. Among connoisseurs of phantasy fiction William Hope Hodgson deserves a high and prominent rank; for triumphing over a sadly uneven stylistic quality, he now and then equals the best masters in his vague suggestions of lurking worlds and beings behind the ordinary surface of life.”(12)

Famed occult author Dennis Wheatley included Hodgson’s works in his 1935 anthology A Century of Horror Stories, and admitted that he was greatly influenced by him.(13) Today, Hodgson is also cited as a direct influence by science fiction author Terry Pratchett and filmmaker Guillermo del Toro.(14) Hodgson’s character Thomas Carnack also became a fixture in Alan Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, testament to an enduring legacy sadly cut short by German artillery more than a century ago.

Source Notes

1. Bruce, 121.

2. Ibid.;

https://williamhopehodgson.wordpress.com/

; http://greydogtales.com/blog/roots-weird-william-hope-hodgson-discussed/.

3. Kalush and Sloman, 143-46.

4. Queen, 64.

5.

https://williamhopehodgson.wordpress.com/

; http://greydogtales.com/blog/roots-weird-william-hope-hodgson-discussed/.

6. Ibid.

7. Moskowitz, 22.

8 Pringle, 273-75. The Times reported that he had been killed on April 17.

9. Everts, 26;

https://williamhopehodgson.wordpress.com/

; http://greydogtales.com/blog/roots-weird-william-hope-hodgson-discussed/.

10. Lovecraft, 9.

11. Ibid., 57-59.

12. Ibid., 104.

13. Anderson, 7-11.

14. Pratchett, 100; https://www.austinchronicle.com/screens/2002-03-08/84931/.

Bibliography

Books

Anderson, Douglas A. Adrift on the Haunted Seas: The Best Short Stories of William Hope Hodgson. Cold Springs Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Press, 2006.

Bruce, Samuel W. “William Hope Hodgson.” In Darren Harris-Fain, British Fantasy and Science-Fiction Writers Before World War I. Dictionary of Literary Biography. Volume 178. London: Gale Research, 1997.

Everts, R. Alain. Some Facts in the Case of William Hope Hodgson: Master of Fantasy. New York: Soft Books, 1987.

Kalush, William, and Sloman, Larry. The Secret Life of Houdini: The Making of America's First Superhero. London: Simon & Schuster, 2008.

Lovecraft, H. P. The Annotated Supernatural Horror in Literature. New York: Hippocampus Press, 2000.

Moskowitz, Sam. Out of the Storm: Uncollected Fantasies by William Hope Hodgson. New York: Donald M. Grant, 1973.

Pratchett, Terry. “On The House on the Borderland.” In Stephen Jones and Kim Newman, Horror: Hundred Best Books. New York: Carroll & Graf, 1998.

Queen, Ellery. Queen's Quorum: A History of the Detective-crime Short Story as Revealed in the 106 Most Important Books Published in this Field Since 1845. New York: Biblo & Tannen Publishers, 1951.

Stableford, Brian. “Hodgson, William Hope.” In David Pringle, editor, St. James Guide to Horror, Ghost & Gothic Writers. London: St. James Press, 1998.

Internet Resources

https://williamhopehodgson.wordpress.com/

http://greydogtales.com/blog/roots-weird-william-hope-hodgson-discussed/