A Corner of Imperial Russia in Hesse: Schloss Fasanerie and the Tragedy of Grand Duchess Alexandra Nikolaevna

by Greg King

It is a room frozen in time. Relatively small, it retains the elaborate, fussy, décor of the era in which it was created, a cross between early Victorian, Biedermeier, and gilded opulence. A porcelain chandelier, awash with foliage and flowers, hangs above a deeply patterned carpet of green, blue, and mauve. Blue silk, woven with a design of swags and tassels in silver, cloaks the walls. A large, gilded, Renaissance-revival-style dressing table, canopied in lace and mauve silk, nestles in one corner, holding elaborate candelabra and a silver-framed mirror. Frames of gold and Karelian birch display miniature watercolors and oils of Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaievna and the future Emperor Alexander II. Overstuffed slipper chairs, upholstered in mauve chintz, stand near sn elaborate mahogany chest before the lace-draped window. In it is a fussy silver toilette service made in St. Petersburg in 1844, with brushes, combs, scent bottles, awaiting a mistress who never used it, never set foot in this boudoir designed especially for her, with reminders of her beloved homeland and images of the family she had left behind.(1) How this bit of Russia came to be preserved in the Hessian hunting lodge of Schloss Fasanerie is a tale of tragedy.

At the time of the room’s creation in 1844, ties between the Romanovs and the Hessian Royal Family were firmly established. In 1773, Tsesarevich Paul, son and heir of Catherine the Great, had married Princess Wilhelmina of Hesse-Darmstadt, who took the name Natalia Alexeievna after converting to Orthodoxy. Although Paul adored her, the new Grand Duchess did not share his feelings, though –owing to her exceptional ambition – she attempted to convince him to plot against his mother to take the throne. She died after giving birth to a stillborn child in 1776.

Happier – at least for the first decade or so – was the union between Nicholas I’s heir Tsesarevich Alexander (the future Alexander II) and Princess Maximiliane Wilhelmine Auguste Sophie Marie of Hesse and by Rhine in 1841. Converting to Orthodoxy, she took the name Maria Alexandrovna. The couple was devoted to each other, although the shy, serious Maria never felt entirely comfortable living amid the immense ceremony of the Russian Court.

A third union between the Romanovs and the Hessians came in January 1844, when Grand Duchess Alexandra Nikolaevna married Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Hesse. It was for the unfortunate Alexandra that this room was created.

Grand Duchess Alexandra Nikolaevna was born on June 12/24, 1825, just six months before her father took the Russian Throne as Nicholas I. She was the youngest daughter of Nicholas and his wife Alexandra Feodorovna and had been born in the Alexander Palace at Tsarskoye Selo. Called “Adini,” she enjoyed a relatively happy childhood at Gatchina, Tsarskoye Selo, Peterhof, the Anichkov Palace, and the Winter Palace. Intelligent and well-educated, Alexandra had a gift for music and played piano and sang equally well. It was a gift cultivated by Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, who invited music teachers from Italy to train her youngest daughter.

Alexandra grew into a beautiful young woman, who inherited her mother’s dark hair and blue eyes. People were struck by her gentleness, amiability, and effervescent personality. Very religious, she adored history and perplexed her siblings by studying ancient battles and legends. Her older sister Olga Nikolaevna, who later became Queen of Württemberg, remembered: “She always shone with joy, but immediately changed her expression as soon as a conversation about something serious began. In prayer I closed my eyes to concentrate; she, on the contrary, opened her eyes wide and raised her hands, as if wanting to embrace heaven. She, who had been so impatiently waiting for the moment when she would get into society, after only one year, or rather one winter, was disappointed by the emptiness she had encountered. ‘Life is only a corridor,’ she said, ‘only preparation.’”(2)

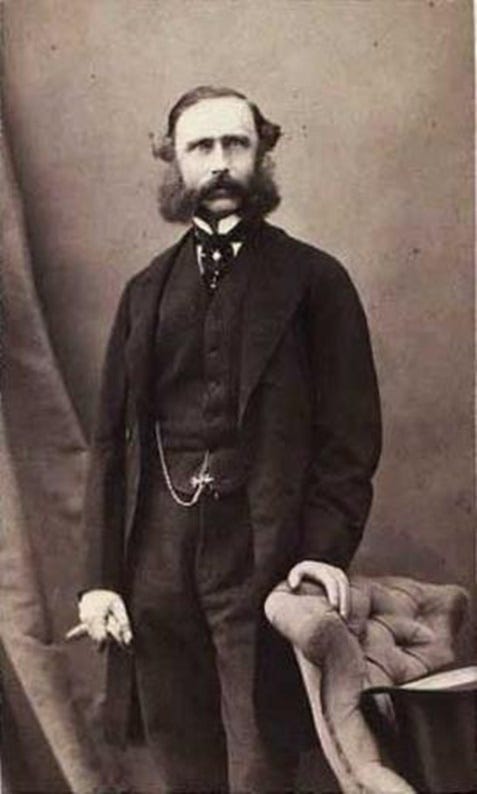

In the summer of 1843, Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Hesse-Kassel arrived in St. Petersburg. Born in 1820, he was the only son of Wilhelm I, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel and Princess Louise Charlotte of Denmark. At the time, he was not only third in line to the Danish throne but also his father’s successor as Landgrave. Fritz, as he was known in the family, had spent most of his life in Denmark to strengthen his claim on the throne, serving in the Army there. He thus seemed eminently eligible as a suitor. He came to St. Petersburg intending to meet and propose to Olga Nikolaevna, Nicholas I’s second daughter. Olga was aware of the purpose of the visit, but was surprised when Fritz quickly turned his attention to the younger Grand Duchess Alexandra Nikolaevna. Seeing that the attraction was mutual, Olga stepped back and let nature take its course. Soon, Alexandra and Fritz were engaged. “We love each other so much,” Alexandra confessed to her sister Olga.(3)

On January 16/28, 1844, Alexandra and Fritz were married in the cathedral of the Winter Palace. The couple remained in Russia as Fritz’s uncle King Christian VIII of Denmark undertook renovations on a mansion in Copenhagen as well as on Bernstorff outside the city, the two residences being his wedding gifts to the couple. Fritz also ordered private apartments prepared at Schloss Fasanerie in Hesse, which would become their German residence.

Schloss Fasanerie, in the foothills of the Rhȍn mountains south of Fulda, had begun life in 1735 when Prince Abbot Adolph von Dalberg enlarged a hunting lodge built in 1710 on the outskirts of Fulda. Five years later, Amand von Buseck, Prince-Bishop of Fulda, acquired the estate and commissioned Italian architect Andreas Gallaslini to greatly enlarge the existing structure into a true palace. Long wings were added to the central block and courtyards were enclosed. The rooms within were executed in Baroque style. It was finally completed in 1751 by architect Johann Dientzenhofer for Elector Friedrich II of Hesse-Kassel.(4)

After the fall of the Prince-Bishops in 1803, Fasanerie passed to the Nassau family. In 1806 it was occupied by Napoleon’s army, suffering the indignity of serving as a military hospital, during which it was damaged and many of its Baroque interiors largely destroyed. In 1816 it was awarded to the Electors of Hesse. Wilhelm II of Hesse asked architect Johann Conrad Bromseis to restore the Schloss and to transform the interior according to neoclassical ideas between 1825-1827.(5)

The finished Schloss was set within a 100-acre park. Close to the building, the gardens were formalized according to Baroque taste, but these soon gave way to an English-style landscaped park of meadows and lakes fringed by woods. The residence was a sprawling building, its wings encompassing four courtyards. Walls washed in white contrasted with the modified double-Mansard roofs of red tile. Within, as one author later noted, were “a large suite of rooms staggering for their beauty and perfect state.”(6)

The Emperor’s Staircase was a magnificent bit of baroque decoration, all creamy white, with Corinthian pilasters rising to a vaulted ceiling adorned with stucco reliefs surrounding the central painting. The staircase took its name from twelve busts of the Cesars decorating niches. Beyond were a suite of lavishly-appointed state rooms: the Heron Hall, decorated with large canvases by Johann Heinrich Tischbein and originally painted for Landgrave Wilhelm IX for his hunting lodge at Wilhelmsbad; the Music Room, with scenic wallpaper painted by Dufour in 1820 depicting the travels of Antenor and a suite of Empire furniture; and the Dining Room, with a ceiling painted by Emanuel Wohlhaupter and table displaying a magnificent ormolu centerpiece with candelabra and epergnes made in Berlin in 1818.(7)

The Private Apartments were more reflective of the mid-Nineteenth Century, with a mixture of Empire, Biedermeier and early Victorian, overstuffed sofas and chairs. On Fritz’s orders, a suite of rooms was prepared for his new wife: a bedroom, study, dressing room, and boudoir. Special pieces of furniture, along with carpets and paintings, were sent from St. Petersburg with careful instructions as to arrangement. The Prince was determined that his wife would have at least a small piece of her beloved Russia in Hesse when they visited Fasanerie.

Alas, it was not to be. Alexandra had always been delicate, and before her marriage she had often suffered from severe colds. Within a few months after her marriage, she was diagnosed with tuberculosis. By this time, she was also pregnant, expecting her first child that autumn. “Doctors prescribed rest and put her to bed for three weeks,” her sister Olga later wrote. Alexandra struggled to breathe as the weeks passed; she coughed incessantly and was unable to sleep. “She lost so much weight,” Olga remembered, “that her lips no longer covered her teeth, and her ragged breathing forced her to keep her mouth open….Her wedding ring fell off as her finger was so thin.”(8)

On July 29/August 10, Alexandra went into premature labor. At ten that morning she gave birth to a five-month-old son. Suspecting that the child would not live, Fritz arranged for a Lutheran pastor to immediately baptize his son, who was given the names Friedrich Wilhelm Nicholas. The baby died after three hours, and Alexandra slipped into a coma, dying at four that same afternoon. Alexandra was buried in the Cathedral of the Fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul in St. Petersburg, while Fritz took his dead son to Germany to bury him in the family tomb in Rumpenheim.

Fritz was devastated by Alexandra’s death. He waited nine years before marrying a second time. His bride was his first cousin Princess Anna of Prussia. There is little suggest that this was a love match: Fritz never ceased to mourn his lost Alexandra, but he needed a male heir. Anna provided him with six children, but the marriage was a failure. Anna, high-minded and artistically inclined, preferred music and books to social life. She was further isolated in 1866 when Fritz sided with Austria in the Seven Weeks’ War over her native Prussia. Her relatives blamed her, and when the conflict ended, Prussia exacted revenge. Electoral Hesse was annexed, and Fritz lost Fasanerie. The Schloss was only returned to him in 1878. Thereafter it became the couple’s principal residence. Fritz died in 1884, his widow retained occupancy until her death in 1918.(9)

Fasanerie suffered severe damage during World War II from American bombers. In 1948 Landgrave Philipp of Hesse decided to restore the schloss, a task which took him more than twenty years. He collected paintings, porcelain, and furniture from other Hessian residences and brought them to Fasanerie, recreating its exquisite rooms and adding museum displays that the public continues to enjoy.(10)

Throughout the years, one room has miraculously remained untouched: the boudoir meant for Alexandra Nikolaevna. It offers visitors a touching reminder of the fragile young woman who was to be mistress here but who, tragically, never set foot in Schloss Fasanerie.

Source Notes

1. Radkai, 77.

2. Olga Nikolaevna.

3. Ibid.

4. https://www.schloss-fasanerie.de/startseite/.

5. https://www.schloss-fasanerie.de/startseite/; Hunter-Stiebel, 91, 263; Radkai 78.

6. Nicolson, 228.

7. Nicolson, 231; Hunter-Stiebel, 78, 225; Radkai, 79-89.

8. Olga Nikolaevna.

9. https://www.schloss-fasanerie.de/startseite/; Hunter-Stiebel, 268.

10. https://www.schloss-fasanerie.de/startseite/; Details drawn from Miller, Dobler, and Klössel; Hunter-Stiebel, 225; Petropoulos, 356-57.

Bibliography

Hunter-Stiebel, Penelope. Hesse: A Princely German Collection. Portland, OR: Portland Art Museum, 2005.

Miller, Markus, Andreas Dobler, and Christine Klössel. Schloss Fasanerie: Museum und Kunstsammlung des Haus Hessen. Hamburg: Schenck Verlag, 2012.

Nicolson, Nigel, editor. Great Houses of the Western World. New York: Spring Books, 1972.

Olga Nikolaevna, Grand Duchess, Queen of Württemberg. Memoirs. In author’s possession.

Petropoulos, Jonathan. Royals and the Reich: The Princes von Hessen in Nazi Germany. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Radkai, Marton. “Fasanerie: A German Castle Preserves the Rich History of an Ancient Dynasty.” In House and Garden, Volume 162, No. 1, January 1990.

Great read, I felt like I was present.

BTW Fasanerie is such a beautiful place I would love to visit it again.